For a few years now I have been arguing that in order to accomplish change in scholarly infrastructure, it likely is an inefficient plan by funding agencies to mandate the least powerful players in the game, authors (i.e., their grant recipients). The legacy publishing system still exists because institutions pay for its components, publishers. As for-profit corporations, as long as the money is flowing, publishers could not care any less what is on the pages the publish, making author behavior all but irrelevant. Moreover, so-called Big Deal packages (both for subscriptions and for open-access publishing) cement the status of publishers, irrespective of what portfolio they are currently offering.

In this situation, the only way in which forcing authors to publish in certain ways makes any sense at all is politically: there is little authors can do other than to comply, as they have no power and need the funding agencies in order to be able to do their research. So from this perspective, authors are the weakest link and the one with the least capabilities to raise any effective objections other than venting online. As we have seen from such previous mandates, most notably the NIH open access mandate from 2008, the amount of change to be gained from such mandates is rather modest: some percentage of articles may get accessible to the non-subscribing public at some point, while the rest of the problems we have accumulated remain firmly cemented in place. As described before, access to the literature currently ranks among the least worrisome problems we have in scholarship.

this means that while in 2008 the increase in access to a portion of the medical literature brought about by the NIH mandate may have been a significant step forward, today, more than a decade later and with no major paywall obstacles to speak of any more, one may wonder whether a marginal improvement on a nearly negligible problem is worth all the efforts currently put into mandates such as those of, e.g., Plan S.

Especially when looking at the kind of change that could be brought about by shifting the massive funds institutions pay for publishers (about ten times the actual publishing costs), it is straightforward to ask, whether Plan S is more Sympolpolitik (a German saying for symbolic politics that only shows off its attempts at making politics rather than to achieve actual change) than Realpolitik?

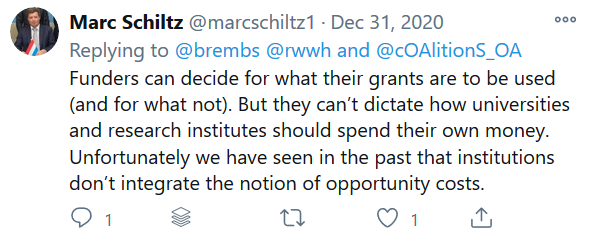

When confronted with this question on Twitter, one of the main designers of Plan S, President of Science Europe Marc Schiltz, first tried to deny that funding agencies even have the capability of mandating institutions to do anything:

I then explained that at least in Germany, the DFG, for instance, mandates that institutions follow good scientific practice and that the DFG guidelines for good scientific practice have to be incorporated into any institution’s policies in a legally binding manner, if their applications are to be considered for funding. Above and beyond such general mandates, there can also be specific mandates, such as those for Next Generation Sequencing machines, where only researchers can apply, whose institutions have the specifically required infrastructure. I had talked to a program director at the NSF, who confirmed that similar requirements were in place also at the NSF and NIH in the US.

Confronted with such a falsification of his initial claim, Marc Schiltz then retreated to the position that not all funding agencies are like the DFG, NIH or NSF:

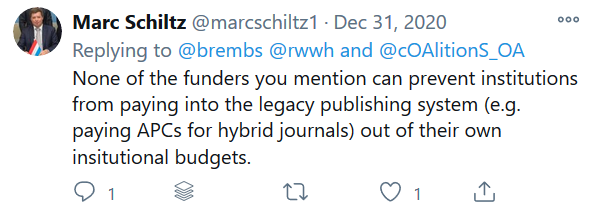

And then asserted that he couldn’t even think of a way how funding agencies could prevent institutions from paying for legacy publishing infrastructure, even if funding agencies had the power to mandate institutions to invest in modern infrastructure:

Of course, once the general concept of funding agencies deciding which institutions are worthy of getting their money is established, it is technically easy to come up with ways in which funding agencies could influence also institutional decisions about funding for legacy systems.

For instance, it would be technically easy (but practically more or less difficult depending on the funder) to influence institutional decisions with regard to subscription payments. Ulrich’s list of serials currently lists over 30k peer-reviewed scholarly journals. Funders could influence how many subscriptions an institution can have until they become ineligible for funding. Or, in places where overhead payments are under the control of the funder, they could start with a softer approach, e.g., cut all overhead payments to institutions who do not report the number of subscriptions to journals, or which exceed, say, 10k journal subscriptions. Institutions with less than 10k subscriptions but more than 5k get 50% of the regular overhead, those with more than 500 but less than 5k get 75% of the overhead, those with less than 500 get 90% and only those without any subscriptions get the full overhead payment.

APC payments can be treated analogously, of course, either by looking at the volume, i.e., number of articles, or the amount spent. In a similar way, institutions that do not report any such figures in a verifiable way become ineligible for funding.

A step down from that, it would be easier for funding agencies to ensure that institutions invest in modern digital infrastructure, by making institutions ineligible for funding that do not have, e.g., a platform where text/narrative, data and code are taken care of and interoperate. Most, if not all funders already have an eligibility requirement for “basic infrastructure”, so they would only need to update that and specify what qualifies as “basic infrastructure” (surely, this would be different today than, say, 30 years ago). User uptake of this basic infrastructure is then ensured in the Liège way, i.e., by funders simply ignoring any research output that is not on such a platform when assessing grant proposals. Such a procedure has been proven very effective for over a decade now, by all the institutions that have implemented one. Centralized access to such a decentralized scholarly library could be established via technologies such as Open Research Central, or analogous implementations.

Easier still, funders could decide that only researchers at institutions that are DORA signatories are eligible for funding. Not at a DORA institution? Too bad, don’t even bother to apply. That would be a truly massive blow to the pernicious power of journal rank! It is clear that this is one of the also practically easiest options as some funding agencies have already implemented such mandates. Funders such as Wellcome or Templeton World Charity Foundation already today require their recipient institutions to sign DORA or an equivalent:

“All Wellcome-funded organisations must also publicly […] sign the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, Leiden Manifesto or equivalent.”

“We expect [Templeton World Charity Foundation] Grantees that are research institutions to have a statement of commitment to implementing the DORA principles on their website – this should be prominent and accessible”

Why are the remaining funding agencies not following suit? Why do most funding agencies still fund institutions that have not signed DORA?

By now, it is becoming quite clear that actual change in infrastructure reform does not require new technology, nor additional funds and does not require neither the mind of an Einstein nor the imagination of a Picasso to come up with ways to mandate change where recalcitrant institutions have proven, time and again over the last three decades, that voluntary change is out of the question. Of course, funding agencies may claim that it is time consuming, practically difficult or a lot of work to implement such mandates on institutions. However, what do such excuses mean other than these funders simply not considering the trifecta of the main problems scholarship is facing today (reliability, affordability and functionality) as being important enough to make this extra effort?

In order to convince Marc Schiltz and perhaps cOAlition S (and, in consequence, other funders world-wide) that it is indeed in their power to make change happen without oppressing the least powerful, my task is now to compile a list of cOAlition S members that differentiates between those that spend their funds on any institution, no strings attached, and those funders that have implemented eligibility criteria such as those of the DFG, NSF and NIH. This list is currently under construction (thanks for any help!). So far, it looks as if the different cOAlition S funders are not nearly as different as Marc Schiltz claimed. For most funding agencies I could quickly find a page detailing the eligibility criteria or requirements. Any help in completing this effort is appreciated.

If the results do not change dramatically from what I could find, it appears that the only thing these funding organizations need to tweak is their eligibility criteria/requirements (e.g., by making their “basic infrastructure” requirements more specific), in order to accomplish change much more effectively (affecting all participating institutions at once) than with mandates on individual grant recipients. Why did they not go that route in the first place? What are they waiting for now?

UPDATE:

In something that must be exceedingly rare on Twitter, Marc Schiltz finally conceded that mandating institutions would be a feasible route and also confirmed that “soft” requirements such as only funding DORA signatory institutions would be an easier first target than, e.g., mandating institutions to stop payments to legacy publishers: