Lately, there has been some public dreaming going on about how one could just switch to open access publishing by converting subscription funds to author processing charges (APCs) and we’d have universal open access and the whole world would rejoice. Given that current average APCs have been found to be somewhat lower than current subscription costs (approx. US$3k vs. US$5k) per article, such a switch, at first, would have not one but two benefits: reduced overall publishing costs to the taxpayer/institution and full access to all scholarly literature for everyone. Who could possibly complain about that? Clearly, such a switch would be a win-win situation at least in the short term.

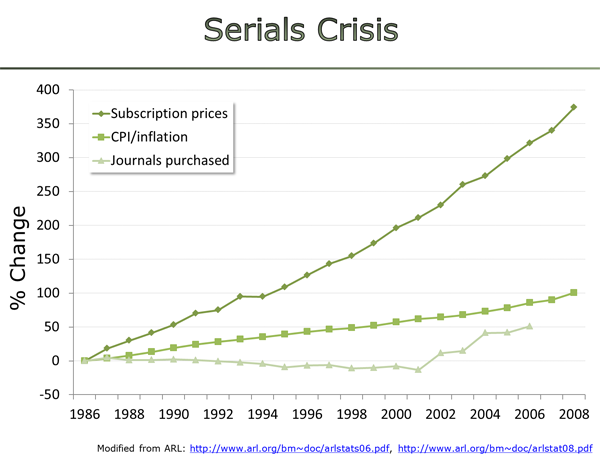

However, what would happen in the mid- to long-term? As nobody can foresee the future with any degree of accuracy, one way of projecting future developments is to look at past developments. The intent of the switch is to use library funds to cover APC charges for all published articles. This is a situation we have already had before. This is what happens when you allow publishers to negotiate prices with our librarians – hyperinflation:

Given this publisher track record, I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.

Given this publisher track record, I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.

I’m not an economist, so I’d be delighted if there were one among the three people who read this blog (hi mom!), who might be able to answer the questions I have.

The major players in academic publishers are almost exclusively major international corporations: Elsevier, Springer, Wiley, Taylor and Francis, etc. As I understand it, it is their fiduciary duty to maximize the value for their shareholders, i.e., profit? So while the currently paid APCs per article (about US$3k) seem comparatively cheap (i.e., compared to currently US$5k for each subscription article), publishers would not be offering them, if that would entail a drop in their profit margins, which currently are on the order of 40%. As speculated before, a large component of current publisher revenue (of about US$10bn annually) appears to be spent on making sure nobody actually reads the articles we write (i.e., paywalls). This probably explains why the legacy subscription publishers today, despite receiving all their raw material for free and getting their quality control (peer-review) also done for free, still only post profit margins under 50%. Given that many non-profit open access organizations post actual publishing costs of under US$100, it is hard to imagine what else other than paywall infrastructure would cost that much, given that the main difference between these journals are the paywalls and not much else. By the way, precisely because the actual publishing process is so cheap, the majority of all open access journals do not even bother to charge any APCs at all. There is something beyond profits that makes subscription access so expensive and any OA scenario would make these costs disappear.

So let’s takes the quoted US$3k as a ballpark average for future APCs on a world-wide scale. That would mean institutional costs would drop from the current US$10bn to US$6bn annually world wide. Let’s also assume a generous US$300 of actual publishing costs per article, which is considerably more than current costs with arXiv (US$9) or SciELO (US$70-200) or current median APCs (US$0). If this switch would happen unopposed, the publishers would have increased their profit margin from ~40% to around 90% and saved the tax payer a pretty penny. So publishers, scientists and the public should be happy, shouldn’t they?

Taking the perspective of a publisher, this scenario also entails that the publishers have wasted around US$4bn in potential profits. After all, today’s figures show that the market is worth US$10bn even when nobody but a few libraries have access to the scholarly literature. In the future scenario, everyone has access. Undoubtedly, this will be hailed as great progress by everyone. After all, this is being used as the major reason for performing this switch right now. Obviously, increased profit margins from 40% to 90% is seen as a small price to pay for open access, isn’t it? Wouldn’t it be the fiduciary duty of corporate publishers to regain the lost US$4bn? After all, why should they receive less money for a better service? Obviously, neither their customers (we scientists and our librarians), nor the public minded an increase in profit from 40% to 90%. Why should they oppose an increase from 90% to 95% or to 99.9%? After all, if a lesser service (subscription) was able to extract US$10bn, shouldn’t a better service (open access) be able to extract 12 or 15bn from the public purse?

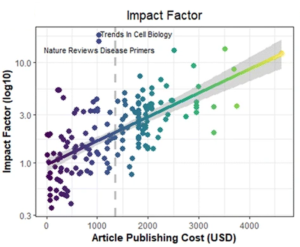

One might argue that this forecast is absurd, the journals compete with each other for authors! This argument forgets that we are not free to chose where we publish: only publications in high-ranking journals will secure your job in science. These journals are the most selective of all journals. In the extreme cases, they only publish 8% of all submitted articles. This is an expensive practice as even the rejected articles generate some costs. These journals are on record that they would have to charge around US$50,000 per article in APCs to maintain current profits. It is hence not surprising that also among open access journals, APCs correlate with their standing in the rankings and hence their selectivity:

It is reasonable to assume that authors in the future scenario will do the same they are doing now: compete not for the most non-selective journals (i.e., the cheapest), but for the most selective ones (i.e., the most expensive). Why should that change, only because now everybody is free to read the articles? The new publishing model would even exacerbate this pernicious tendency, rather then mitigate it. After all, it is already (wrongly) perceived that the selective journals publish the best science. If APCs become predictors of selectivity because selectivity is expensive, nobody will want to publish in a journal without or with low APCs, as this will carry the stigma of not being able to get published in the expensive/selective journals.

It is reasonable to assume that authors in the future scenario will do the same they are doing now: compete not for the most non-selective journals (i.e., the cheapest), but for the most selective ones (i.e., the most expensive). Why should that change, only because now everybody is free to read the articles? The new publishing model would even exacerbate this pernicious tendency, rather then mitigate it. After all, it is already (wrongly) perceived that the selective journals publish the best science. If APCs become predictors of selectivity because selectivity is expensive, nobody will want to publish in a journal without or with low APCs, as this will carry the stigma of not being able to get published in the expensive/selective journals.

This, to me as a non-economist, seems to mirror the dynamics of any other market: the Tata is no competition for the Rolls Royce, not even the potential competition by Lamborghini is bringing down the prices of a Ferrari to that of a Tata, nor is Moët et Chandon bringing down the prices of Dom Perginon. On the contrary, in a world where only Rolls Royce and Dom Perignon count, publications in journals on the Tata or even the Moët et Chandon level will only be ignored. Moreover, if libraries keep paying the APCs, the ones who so desperately want the Rolls Royce don’t even have to pay the bill. Doesn’t this mean that any publisher who does not shoot for at least US$5k in their average APCs (better more) fails to fulfill their fiduciary duty in not one but two ways: not only will they lose out on potential profit, due to their low APCs, they will also lose market share and prestige. Thus, in this new scenario, if anything, the incentives for price hikes across the board are even higher than what they are today. Isn’t this scenario a perfect storm for runaway hyperinflation? Do unregulated markets without a luxury segment even exist?

One might then fall back on the argument that at least Fiat will compete with Peugeot for APCs, but that forgets that a physicist cannot publish their work in a biology journal. Then one might argue that mega-journals publish all research, but given the constant consolidation processes in unregulated markets (which is alive and well also in the publishing market as was just reported), there quickly won’t be many of these around any more such they are, again, free to increase prices. No matter how I try to turn the arguments around, I only see incentives for price hikes that will render the new system just as unsustainable as the current one, only worse: failure to pay leads to a failure to make your discovery public and no #icanhazpdf can mitigate that. Again, as before, this kind of scenario can only be worse than what we have now.

tl:dr: The incentives for price hikes in a universal gold open access economy will be even stronger than they are today.

I agree in majority of assumptions, and I would like add one important point.

In late 90s ethical committees approving research plans started to reject much more experiments. Unless you’re willing to relocate sensitive research to countries with lesser ethical standards, you’re virtually unable to reproduce certain experiments today. In such way, old, paywalled articles in experimental biology and medicine are the treasure trove of research that cannot be conducted today. There’s no incentive on the side of a publishers to open that resource.

In addition to APC hiperinflation effect, we will see subscriptions staying in place for much longer than people predict. We just cannot afford loosing that unreproducible (in a sense that you cannot repeat these experiments due to ethical reasons) treasure trove.

We could regain the access to these articles through universal Green OA, but bunch of *$!@%$ [Open Access advocates] made it unfashionable these days.

No need to panic. What you’re describing is simply a market — which where it differs profoundly from what we have today, where every subscription is a little monopoly. Yes, vendors will want to increase prices; but yes, customers will go where the prices are cheaper. It’s the same mechanism that means you can now get a mobile phone that costs a fifth of what something equivalent would have cost a few years ago.

Yes, there will possibly be a Rolls Royce segment. That doesn’t bother me. Fords and Hondas outnumber Rolls Royces 100 to one. They’re not statistically significant. And no-one is going to recruit based on publications in Science’n’Nature once it becomes apparent that the way to get in is by paying for it.

“Yes, vendors will want to increase prices; but yes, customers will go where the prices are cheaper.”

Say, what?

Mike, you appear to use at least one device from Apple, despite that there are functionally and technically equivalent options on the market that cost less than you’ve paid. You’re just an example, that there’s a lot of people that is likely to fall victim to the mechanism Bjoern described above (image, recongnition, prestige or what not). The number is significantly large to keep the prices at this level, or to increase them (verify please on the pricing history or every iphone generation).

How do you know I use an Apple product?

I have a MacBook, which I’ve had since 2009 — six years and counting. In that time, I’ve done about twelve hours of maintenance work on it, or two hours a year on average. Much as I love Debian GNU/Linux, every Debian laptop I’ve owned has needed an order of magnitude more doing to it. So assuming my time is valuable, the MacBook has proved its value over that time.

I can’t think of anything about Science’n’Nature that is analogous to Apple build-quality or operating system/hardware integration.

The proper analogy for the tabloids is not high-quality hardware, but designer-brand handbags.

Too bad I don’t know any handbag brands, damn! 🙂

The way it is now, you’re only allowed into universities if you carry a designer handbag, no matter how many cheap handbags you own and no matter how cheap the non-designer handbags are. In fact, the non-designer brands would be pushed out of the market if they wouldn’t use increased prices to make themselves appear more designer-like.

I probably disagree with most of what you wrote there at least to some extent, but the last sentence does inspire some small glimmer of hope. But that means that for anything like the planned switch to work, you first need to demolish journal rank, before you can even begin to start implementing that switch. If you switch first, they can always justify their costs with the selectivity.

Indeed, if we take your words “in a world where only Rolls Royce and Dom Perignon count, publications in journals on the Tata or even the Moët et Chandon level will only be ignored.”

So we need to get rid of journal ranks. Or better, we need to build ranks independently of publication. Post publication valuation systems, like f1000 reviews, may be one solution?

Absolutely! If we have to keep such metrics (which I am reluctantly conceding), then we better use scientific metrics.

A very important issue remains that the groups paying the costs will change. Currently these budgets are sitting in libraries, and are being explicitly negotiated by librarians.

So…

1. Would that $6b cost be transferred somehow to budgets for buying open access for authors? How? I can’t imagine a university having a shared-journal budget for authors. And if they did, then why would authors take costs into account? What really needs to happen is that the library budget needs to be distributed to authors somehow, but that’s a bureaucratic nightmare.

2. Would there be an economic difference between authors deciding where to publish (since similar-level journals may have different costs) than a librarian negotiating for journals? Probably, but anti-trust and anti-cartel systems would have to be in place. (That is, science and nature have to compete for costs as well as prestige.)

The serials crisis emerged after the second world war along with the entry of commercial publishers in scholarly publishing. Until that point almost all scholarly journal publishing was in the hands of society publishers. Even today scholarly societies are involved in about half of scholarly journals. Close to half of Wiley’s journal portfolio, for example, is actually Wiley publishing on behalf of scholarly societies. Wiley acquired these titles when they acquired Blackwell’s. Many of the scholarly societies outsourced their publishing to Blackwell’s during the 1990’s and early 2000’s when online publishing was expensive and hard, out of the reach for smaller publishers. Today there are many options, including free open source publishing software (OJS) and library publishing services. New journals do not have to follow this path at all, and a great many existing journals could transition away from these corporate partnerships when their contracts come up for renewal. Then, too, we really don’t need the journal format anymore.

I think Carl Bergstrom’s discussion about the economics of subscription vs. author pays is relevant. Especially this bit:

“An author, deciding where to publish, is likely to consider different journals of similar quality as close substitutes. Unlike a reader, who would much prefer access to two journals rather than to two copies of one, an author with two papers has no strong reason to prefer publishing once in each journal rather than twice in the cheaper one.

If the entire market were to switch from reader-pays to author-pays, competing journals would be closer substitutes in the view of authors than they are in the view of subscribers. As publishers shift from selling complements to selling substitutes, the greater competition would be likely to force commercial publishers to reduce their profit margins dramatically.”

Here’s a link to the whole thing:

https://octavia.zoology.washington.edu/publishing/BergstromAndBergstrom04b.pdf

You wrote:

“an author with two papers has no strong reason to prefer publishing once in each journal”

Actually, in my field, if you publish in only one journal, people get the suspicion you have some inside friends, compared to when you publish in many journals, you get your work past any editor/reviewer.

So from that perspective, it is highly unlikely that authors would flock to the cheapest journal and publish all their work there, at least not in biomedicine.

Let’s be clear about what publishers sell: They do not sell a publication service, they sell prestige. The higher the prestige they can promise, the higher the price they can ask for. And it makes no difference whether we are in a reader-pays or in an author-pays model.

Prestige comes from brands. Rolls Royce, Apple, but even more so Prada and Gucci have understood that. As long as the brands reside with shareholder owned companies, an increase in prestige will immediately be followed by an increase in prices.

The obvious solution is: create scholar-owned brands and DO NOT SELL OUT. When you create a journal, make sure that a) the branding is decoupled from technical services and b) that the brand is owned by a learned society or similar. In that way, when the journal gains prestige, the technical service provider cannot use the vendor lock-in to force higher prices since the technical part of the article production can easily be substituted, whereas the brand part can not.

Exactly! Right now, subscription charges are not related to prestige, as they are related to the number of subscribers. Hence, you won’t find Nature, Science nor Cell et al. among the most expensive journals:

https://www.bibliothek.kit.edu/cms/teuerste-zeitschriften.php

However, selectivity is what drives costs and since, in a gold open access world, the few selected authors pay, the price these authors have to pay scales with selectivity. Hence, in a universal gold OA world, publishers would really sell just prestige and not much else (after all, there isn’t much to sell, anyway). So for any publisher, the incentive would be to aim for the top, as any ‘bottom feeder’ journal would carry the stigma of ‘trashcan article’ for their authors.