On May 23, the Council of the EU adopted a set of conclusions on scholarly publishing that, if followed through, would spell the end for academic publishers and scholarly journals as we know them. On the same day, the adoption was followed by a joint statement of support by the largest and most influential research organizations in Europe. At the heart of the goals spelled out in the conclusions and the statement of support is the creation of a “publicly owned and not-for-profit” infrastructure for scholarly publications.

Specifically, the Council

ENCOURAGES Member States and the Commission to invest in and foster interoperable, not-for-profit infrastructures for publishing based on open source software and open standards, in order to avoid the lock-in of services as well as proprietary systems, and to connect these infrastructures to the EOSC

This echos almost verbatim our proposal from 2021 where we outline a replacement for academic journals. In this post, we detail the reasons behind this seemingly radical proposal:

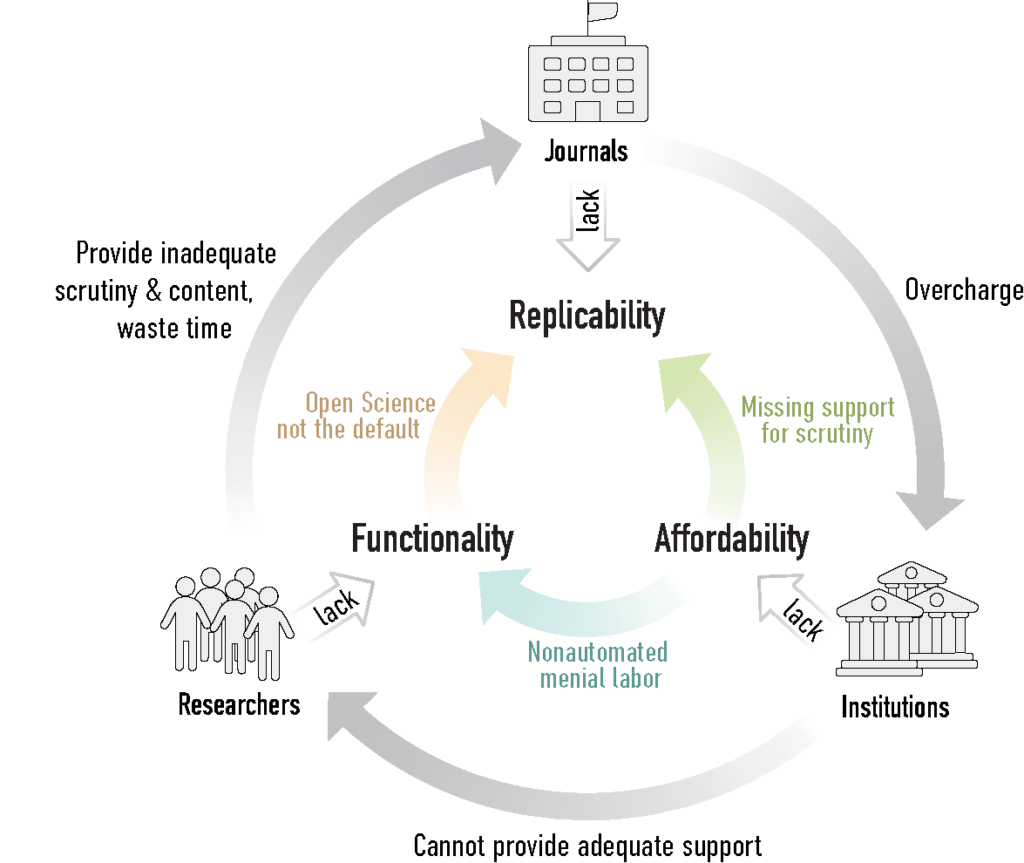

With their supra-inflationary price increases, profit-maximizing journals overcharge (via subscriptions or article processing charges) institutions by a factor of up to tenfold, extracting library budgets with little if anything left for infrastructural development. The resulting lack of infrastructure funds is a crisis of affordability: institutions cannot afford to invest in technology and its human support system that could relieve researchers of clerical tasks such as manuscript submission, data deposition, code publication, etc. This results in a functionality crisis that entails researchers lacking time, functionalities and human support both for efficient scrutiny during the review process as well as for making their own research open and reproducible. Not shown: Journals have apparently not invested their surplus into reviewer support, resulting in little improvement over the last decades, such that researchers are still lacking basic functionalities such as, e.g., comments via authoring system, direct author communication, AI-assisted error and fraud detection, efficient manuscript submission, etc., contributing to the functionality crisis. As the journals keep increasing their prices without a concomitant rise in investments, they fuel the replicability crisis.

This vicious cycle has been allowed to go on for so long, that more and more experts are now calling for precisely such a disruptive break. The time for small, evolutionary steps has passed and the parasitic publishing corporations have shown little willingness over the last decades even to just mitigate, let alone solve the problems caused by their extractive business models. For more than a decade, an ever-growing group of researchers have called to cut out these parasitic middle-men. It now finally seems as if our arguments have been convincing. Everything in the Council’s conclusions reiterates what the open science community has been fighting for in all this time: vendor lock-in needs to be broken, scholarly governance established and fragmenting silos replaced with interoperable, federated infrastructure.

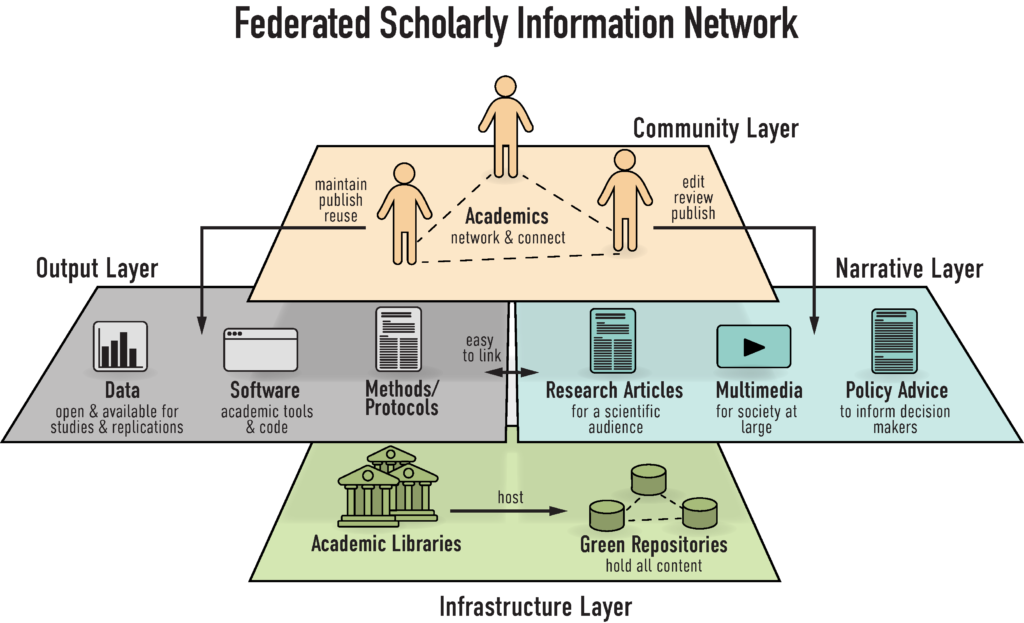

The technical solutions needed for this modernization from 17th century journals to 21 century digital technology are plenty and readily available off the shelf. Scholarship has the choice of either picking pre-existing solutions such as CORE or ORC, or design a new network. In either case, the general structural design of such a network may look something like this:

A federated network of institutional repositories constitutes the underlying infrastructure. Ideally, this infrastructure is designed redundantly, such that large fractions of nodes may go offline and the remaining nodes still provide 100% of the content. Users only directly interact with the output and narrative layers. The output layer contains all research objects, text, data and code. The narrative layer combines research objects in various forms, including research articles. The community layer encompasses standard social technologies such as likes, follows and other network tools (see also “Mastodon over Mammon“). Modified from LSE.

Picking an existing solution such as CORE or ORC comes with the advantage that little new development has to be done and that it is obviously very cheap: everything is already in place and only needs to be expanded. The downsides are that the existing solutions have been designed in the current ecosystem and that may have entailed some historical baggage one would need to identify and fix. Conversely, picking off-the-shelf components to build a replacement from scratch costs more, but has the advantage to be able to build a state-of.the-art system with all the bells and whistles from the ground up. It’s a bit like the choice between buying a used or new car or house.

Obviously, right after the declaration came out, the corporate misinformation machine sprang into high gear. I won’t repeat the misleading, false or sometimes just comically desperate attempts at smearing an obviously well thought-through, sound and logical solution that has been decades in the making. Suffice it to say, there are plenty of reasons why the plans outlined by the Council have drawn such widespread support from all corners of the research community, while the only resistance comes from the monopolistic corporations. This declaration tackles the root of the replicability, affordability and functionality crises. It aims to treat the disease, not the symptoms and has the potential to develop into an effective vaccine against parasitic businesses striving to leech the public purse. Little wonder these businesses fear it so much.

I think we, particularly Indian scientists, created this problem themselves by there diffidence. The journals by the Indian Academies are good, free of cost or at minimal cost, no APCs. But most Indians, including the fellows of Academies themselves feel it below dignity to publish their best papers there. The mirage of impact factors and journal prestige has mislead us completely. Just correcting this is also sufficient to overcome most of our publication problems.

If the journals of the Indian academies make their peer reviews transparent, nothing else is required to create ideal science publishing systems. India can easily lead the way towards sound science publishing systems. But the question is whether Indian Scientists have the mindset to lead the world? This is the only problem to be overcome. Rest we have it all.

Comments are closed.