Universities worldwide currently face a pivotal choice: should they contribute to building a global infrastructure for exchange, science, and discourse, free from the control of oligarchs, to promote democracy, human rights, and digital participation? Or should they continue advertising on private networks, hoping for clicks and marginally increased student enrollment? The Fediverse serves as a litmus test for universities globally: will they align themselves with the likes of Trump, Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos, et al., or actually enact their mission statements by counteracting privatized disinformation and the ensuing erosion of democracies?

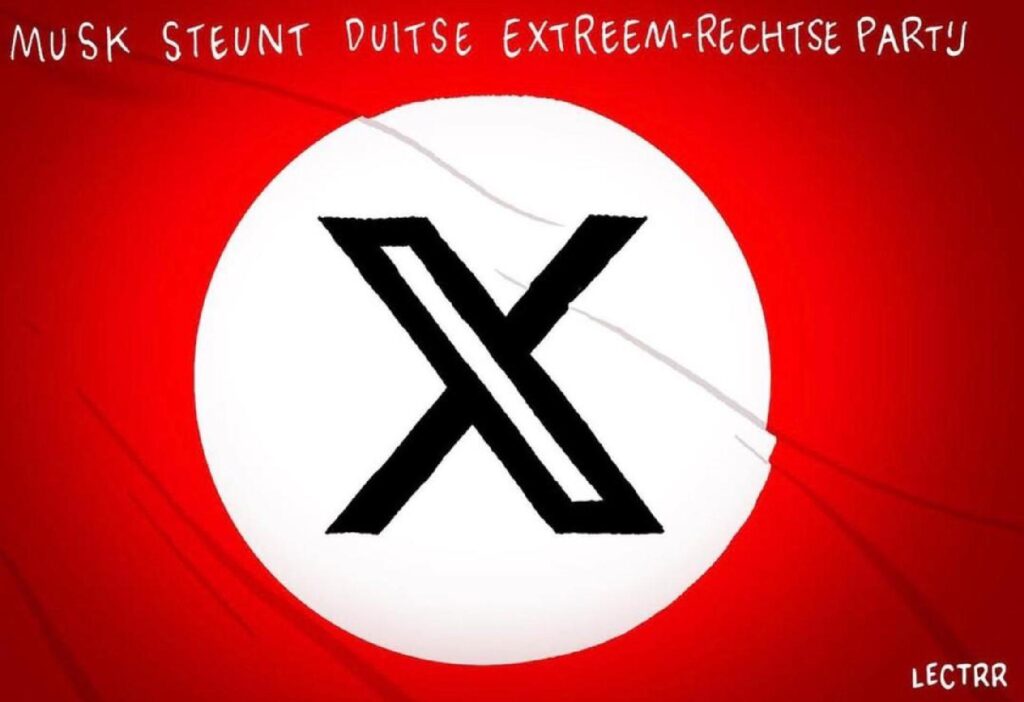

Platforms such as FriendFeed, StudiVZ, and Twitter have historically functioned as digital spaces where academics, researchers, and students gathered to discuss science, exchange ideas, and foster progress. These platforms, however, shared a common fate: they were sold to private owners, subjected to market forces, and eventually fell victim to what Cory Doctorow called “enshittification”—a cycle of increasing commercialization and exploitation, ultimately leading to user abandonment. Currently, Elon Musk’s rebranded platform X (formerly Twitter) is undergoing precisely this process of enshittification and mass user exodus.

Unlike platforms such as Facebook or WhatsApp, which prioritize connections among fiends/acquaintances and operate as “social graphs,” platforms like FriendFeed, StudiVZ, and Twitter were designed to establish “interest graphs,” enabling users to connect based on shared interests. This distinction explains why scholars and those engaged in intellectual pursuits have traditionally gravitated toward the latter platforms. As X collapses under its new management, these users are now migrating to platforms like Meta’s Threads or Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s Bluesky. Yet, it is only a matter of time before the same cycle of enshittification and exodus repeats on these platforms.

A unique opportunity now presents itself, one that was unavailable during the decline of FriendFeed or MySpace. Universities, in particular, stand to benefit from this alternative: the Fediverse. The Fediverse offers an avenue to translate their mission statements into tangible action, in particular for institutions committed to “creating systematic spaces for learning and experience to promote sustainable development,” are aware that “their credibility is measured by how exemplary sustainable solutions are implemented within their sphere of responsibility,” uphold “openness, transparency, and participation” as fundamental principles, ensure “equality of opportunity as well as freedom from discrimination at all levels,” consider the “plurality of worldviews and ways of life,” and maintain a “critical distance from political and societal power” (quotes from the mission statements of some Berlin universities). These same principles inspired universities and public institutions over 30 years ago to develop the decentralized Internet and email, technologies that remain resistant to take-over by private entities still today. Since 2018, the Fediverse has operated on similar principles of decentralization, utilizing public protocols to enable communication between independent servers. Among its many services, Mastodon is especially relevant for universities.

Mastodon functions much like other microblogging platforms—users can post short updates, which are visible to their followers. However, Mastodon differs in its decentralized architecture: users choose their “Mastodon instance,” akin to selecting an email provider. Instances federate with one another, but unlike email, problematic instances can be excluded from the network. For example, Trump’s “Truth Social” is a Mastodon instance that does not federate with others, preventing Mastodon users from seeing posts on Truth Social unless they belong to that specific instance. Universities could harness this decentralization to establish their own instances, shaping the discourse in alignment with their values, rather than the profit-driven motives of private platforms. By doing so, they could create spaces committed to democratic principles and intellectual engagement, free from the manipulations of platform owners.

This makes it immediately clear why it is futile to engage with the likes of Musk and is fanbois on his own platform. It is as pointless as trying to run a “beware the beginnings” campaign in a Nazi pub where everyone simply covers their ears and sings the “Horst-Wessel-Lied“. Similarly, attempting to defend democratic values on Musk’s platform is futile. Not only are these values constantly trampled on from all sides, including by the platform’s owner, but posts defending such values have no chance of being heard. They are systematically suppressed, while content promoting extremist and anti-democratic ideologies—hate, disinformation, racism, sexism, antisemitism, and conspiracy theories—is actively amplified and continuously disseminated. In such a hostile and inhospitable environment, meaningful democratic debate is no longer possible. The same vulnerabilities inherent in X are likely to eventually afflict other private platforms, such as Bluesky, as they succumb to market forces and the insatiable greed of their owners. A more effective approach would be for universities to establish their own digital spaces, reflecting their core values and fostering future generations’ commitment to democratic ideals.

While the current migration of users from X to Bluesky may resemble desert wanderers seeking water in the Namib, there are reasons for their choices. For one, Bluesky has invested millions (including funding from Trump-aligned investors like Blockchain Capital) to mimic Twitter’s interface. Mastodon, by contrast, lacks such resources and, moreover, has deliberately avoided implementing addictive algorithms and toxic design choices. Second, once a small imbalance was achieved, the migrating users were followed by their, ahem, followers, so far to Bluesky. And third, the absence of widespread institutional support for Mastodon since its inception in 2018 has contributed to its slower adoption. As a result, there is no widespread infrastructure for the Fediverse today, akin to what institutions established 30 years ago for web and email servers—technologies that have withstood neo-feudal control and continue to serve as the backbone of online life. From this perspective, universities could arguably seen as bearing some responsibility for the rise of disinformation and populism, as they failed to proactively support the development of a democratic, truth-oriented, digital public sphere in a timely manner.

Universities must now decide how they will position themselves in the realm of social media. To date, most institutions have failed to reconcile their mission statements with their social media strategies. Rarely have they implemented “exemplary sustainable solutions,” promoted “equality and freedom from discrimination,” or maintained “critical distance from political and social power.” Instead, many seem to confuse social networks with some sort of cheap television: one can post advertisements for free and see the “ratings” as follower counts. This mentality explains the initial hesitation to abandon X (“so many followers are still there!”) and now the gradual shift away from it (“we don’t want to appear complicit!”). Such behavior reflects the broader impact of neoliberal ideologies that have reshaped universities into competitive, market-driven entities, eroding their commitment to collaboration and collective progress. The past 30 years of neoliberal ideologization through “New Public Management,” “Corporate Universities,” and “University as a Business” have evidently achieved striking success. Each institution prioritizes its own interests in the competition for students and funding, systematically neglecting synergies through cooperation. “Show over substance” reduces the published mission statements to idle gossip. In times of tight budgets and heightened competition (when are budgets ever not tight?), it is hardly surprising that university administrations would rather allocate two full-time equivalents to polishing the data required by ranking agencies than to genuinely improving university operations—such as setting up a Mastodon instance. The oft-cited (and likely misattributed) dictum from Albert Einstein that “not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted” seems to have been entirely forgotten.

In the coming months, universities’ actions will reveal whether they succumb to neoliberal dogma or uphold their mission statements. Who will leave X when? Where is which university migrating to? Which institutions will establish Mastodon instances? One could use such numbers for a new kind of university ranking…