Over the years, publishers have left some astonishingly frank remarks over how they see their role in serving the scholarly community with their communication and dissemination needs. This morning, I decided to cherry-pick some of them, take them out of context to create a completely unrealistic caricature of publishers that couldn’t be further from the truth. However, I’ll leave the links to the comments, so you can judge for yourself just how out of context they actually have been taken.

Essentially all of these comments were voiced on the blog of the Society for Scholarly Publishing, an organization representing academic publishers. For one of the commenters, Joseph Esposito, it is likely safe to assume that his continued presence as main contributor to the blog means that these viewpoints reflect the general viewpoints of the members of this association closely enough to not warrant dismissal from the site. The other quoted commenter, Sanford Thatcher, is not a contributor to the blog at all, so there is no direct way of estimating how representative his views are. Both commenters are or have been either publishers themselves or consult publishers in various roles.

- Publishers don’t add any value to the scholarly article:

Now you can find an article simply by typing the title or some keywords into Google or some other search mechanism. The Green version of the article appears; there is no need to seek the publisher’s authorized version.

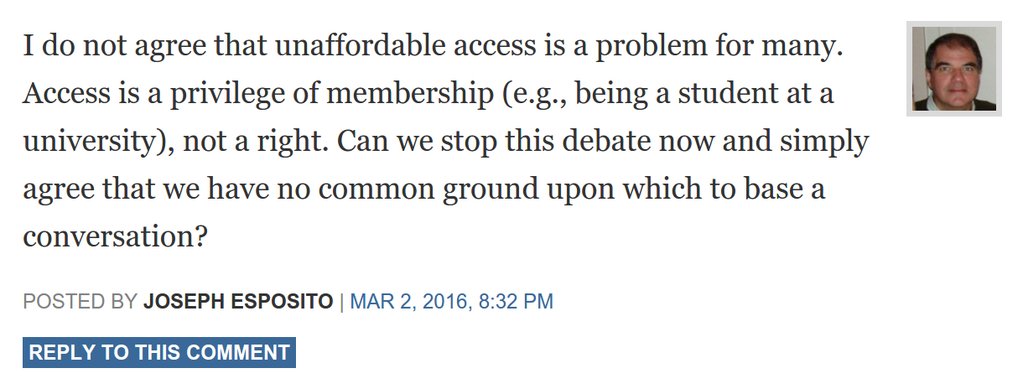

2. Publishers’ business of selling scholarly articles to a privileged few is not negotiable

Screenshot via Mike Taylor

3. The purpose of academic publishers is to make money, not to serve the public interest:

It is not the purpose of private enterprises to serve the public interest; it is to serve the interests of their stockholders. On the other hand, it is the purpose of the federal government to serve the public interest.

4. Governments ought to serve the public interest by funding all scholarly communication:

you should be urging the government to better disseminate the results of the research it sponsors.

Let’s take these comments and completely mangle the impression publishers publicly express of themselves: “We don’t really have anything of value to contribute, but it is our non-negotiable fiduciary duty to make as much money off the public purse as possible. If you want to change that, you should take all the tax-money we’ve suckered you into handing over to us and build a sustainable scholarly communication infrastructure yourselves.” Couldn’t have said it better myself, actually.

I found the last sentence of JoeE’s comment especially memorable, and will try to remember it on future occasions when he’s involved in an OA-related discussion. Which, presumably, he will now recuse himself from.

Well, it’s true. We all know this. I feel the need for a mirror post “How do academic managers see their role?”, as sincere as this one. Who forces researchers to use the services of these publishers, via promotions and grant criteria? Who decides to buy their products?

Oh I’d love to see quotes from administrators! Unfortunately, they usually don’t make such comments in the public sphere. Moreover, much of the adherence to journal rank and productivity is driven out of subjective impressions that this is what counts, sometimes even against the explicit instructions. It also comes from us talking about each other in terms of where we have published an how often. This is virtually impossible to get rid of. In fact, it’s probably easier to get rid of journals than of these habits and superstitions. Hence getting rid of journals is paramount, as I see it.

I will never forget this comment, perhaps 15 years ago, from the president of a major scholarly (mostly scientific) publishing company in the U.S. It startled me (innocent and untutored as I was back then) and I never saw the world quite the same. “The stakeholders we care about are not our readers, i.e., scientists. Rather, they are our shareholders.”

And nothing has changed ever since..

Nothing is forever. I think it would help to point the finger at academic managers. Yes, the publishers have a business, their responsibility is towards their stakeholders. It would be naive to pretend we don’t know this. In the same time, the ones who are essential for the publishers business are the academic managers. What is their excuse? That the publishing system offer numbers which allow them to make decisions. Otherwise said, the excuse of the academic managers is that they delegated their responsibility to the publishers. Something is very wrong with this system.

The one big thing which became obvious after the appearance of Sci-Hub is that the effects of the efforts to shame the publishers (and keeping mum about their academic brothers) are tiny compared to this one technical solution. (I don’t discuss the legality of it, but I point instead to obvious historic analogies with patents wars.) It is therefore possible to disseminate the research results held by the journals. (Btw, who other than the academic manager forces the researcher to give away the copyright? Where is the support for keeping the copyright, in the obvious interest of the university? Whose money spend the consortia which negociate with the publishers for something which is produced by researchers?)

These shaming strategies don’t work without giving an alternative. Publishers have businesses, academic managers waste money for nothing useful, OK. There is no alternative publishing system with obvious advantages for those interested (researchers and their funding bodies). If an alternative existed already, then everybody would have jumped to use it.

The actual system, based on published articles, served well science. Why is, all of a sudden, wrong? Because today we can do much better than to publish an article, after it has been reviewed by peers. Today we can disseminate the whole body of research, not only the story about the research, in the form of a typed article.

The solution, in my opinion, is Open Science. The only advantage of publishing an article, i.e. the peer review, pales when compared with the possibility to assess a research work from the whole body of data which is made available by the researchers.

In conclusion, if we want to play more shame games, in order to speed up the change, then let’s add academic managers and peer review on the list. Researchers have to do this, not librarians, not generic OA activists, because otherwise it would be not credible enough.

Yes, we need an alternative. We should cancel all subscriptions and use the money to implement this alternative. Whoever wants to use the old system has to find funds for themselves to pay for it. At my university, we pay for telephone and snailmail ourselves, while email and skype are paid for.

Managers love gradual approaches. Here is one: an university may create a track (chair or grant) funded by a part of the money wasted with publishers.

This track should reward experimental Open Science practices, instead of ignoring them or instead of forcing generic minimal OS behaviour.

After 5 years, say, audit the results of the Open Science track as compared with the classical track. Just an example. Maybe there are private funders who could support that.

Here are another couple of comments for your collection 🙂

1. Whatever one may think about the relative merits of Green and Gold OA (a matter that my colleagues on the Kitchen and myself have discussed numerous times) or the economic implications of embargoes of various lengths, what is clear is that Green OA has no promise of delivering augmented revenues to the publisher, but Gold OA opens up a new customer, the author him or herself, who in many instances pays for the article to be OA. Gold OA, in other words, represents a business opportunity, whereas Green OA represents a business problem. — Joseph Esposito

source: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/12/03/how-plos-one-can-have-it-all/

2. It was not my intention to be dismissive of the rather noble intentions here. What I am trying (perhaps poorly) to say is that publishing is not at the root of the issues being described. What Pandelis is talking about here is the academic career structure and the entire system of research funding. There are more people who want jobs and funding than the system will support, hence, over the last few hundred years, a competitive ecosystem has evolved. Publishing reflects this system, but is not directly responsible for the behaviors the system both inspires and requires.

If you remake the system of scholarly publishing, it will not solve the inherent issues that are caused by the career and funding infrastructure in place. Take publishing out of the picture and the same pressures still exist and something else will just move into the same space and exhibit the same problems.

Rather than treating the symptoms, one must treat the disease itself. Reform the academic career and funding structure and publishing will have no choice but to adapt to the new system put in place.

And that is why I have said above that the problems that Pandelis is trying to solve here are much bigger than publishing, and that while publishing makes an easy target (everyone hates publishers after all), it’s a distraction from the actual issues he’s trying to solve, issues which are much harder, and require taking on those in power in academia and at funding agencies, who are going to be much more difficult targets. Those for whom the current system works quite well are going to be difficult to convince, and they are the same ones who hold all the power. — David Crotty (comments section)

source: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2016/03/23/ask-the-chefs-what-is-the-biggest-misconception-people-have-about-scholarly-publishing/

Excellent quotes, so many thanks!