A few years ago, I came across a cartoon that seemed to capture a particular aspect of scholarly journal publishing quite well:

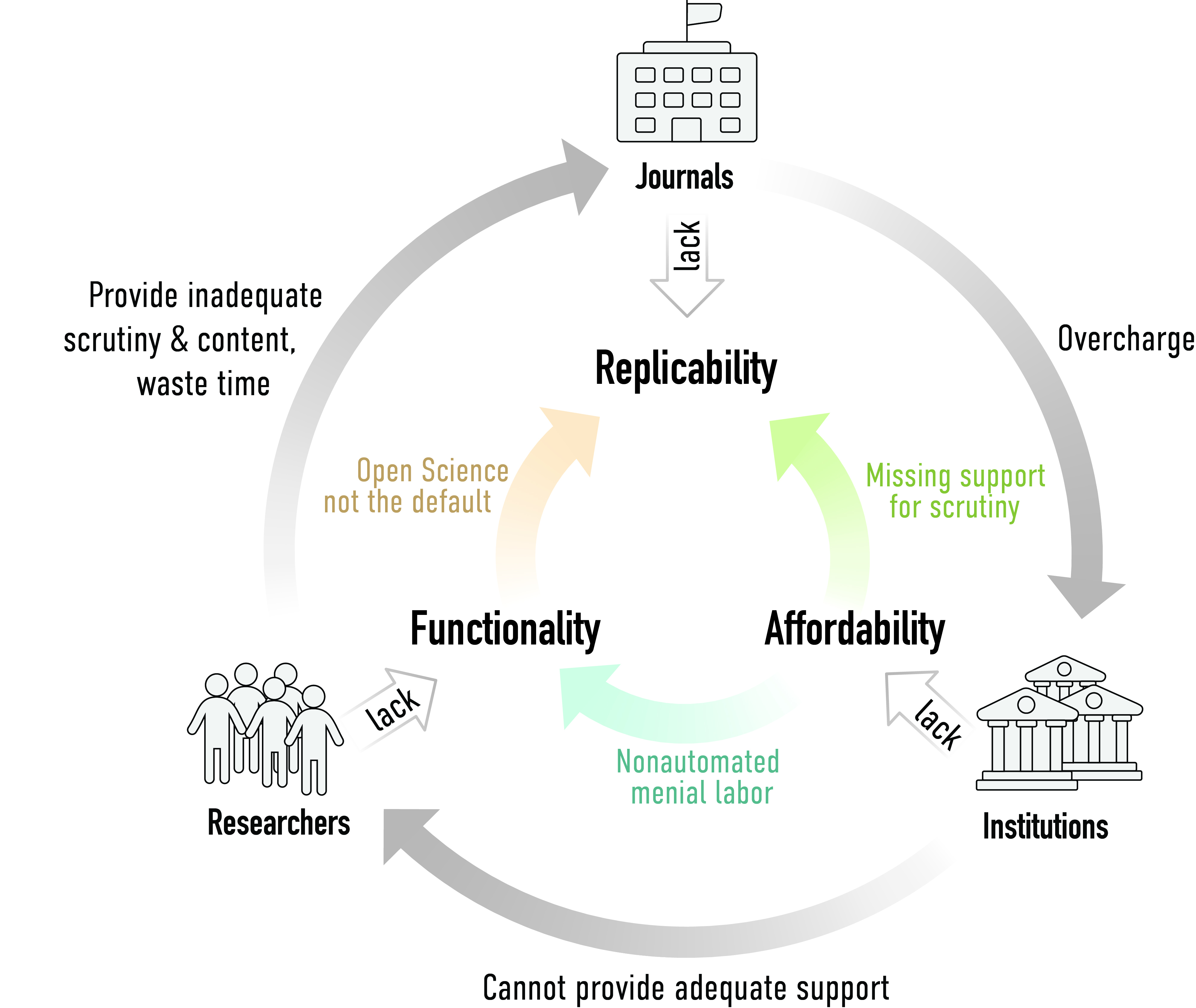

The academic journal publishing system sure feels all too often a bit like a sinking boat. There are many leaks, e.g.:

– a reproducibility leak

– an affordability leak

– a functionality leak

– a data leak

– a code leak

– an interoperability leak

– a discoverability leak

– a peer-review leak

– a long-term preservation leak

– a link rot leak

– an evaluation/assessment leak

– a data visualization leak

etc.

A more recent leak that has sprung up is a papermill leak. What is a ‘papermill’? Papermils are organizations that churn out journal articles that are made to look superficially like research articles but basically only contain words without content. How big of a problem are papermills for science?

In a recent article, the Guardian cites Dorothy Bishop with regards to papermills:

In many fields it is becoming difficult to build up a cumulative approach to a subject, because we lack a solid foundation of trustworthy findings. And it’s getting worse and worse.

The article states that something on the order of 10,000 articles a year being produced by papermills poses a serious problem to science. These numbers most certainly are alarming! The article also cites Malcolm Macleod:

If, as a scientist, I want to check all the papers about a particular drug that might target cancers […], it is very hard for me to avoid those that are fabricated. […] We are facing a crisis.

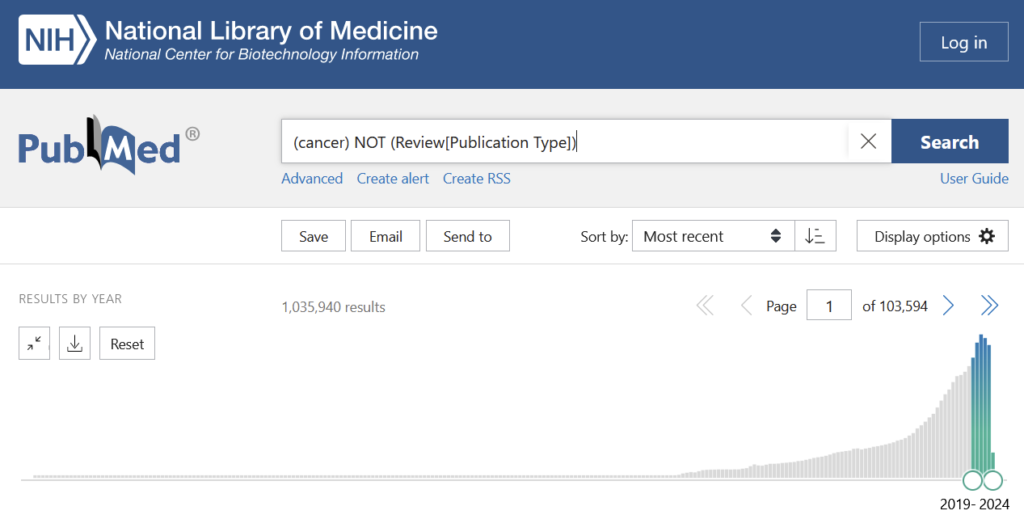

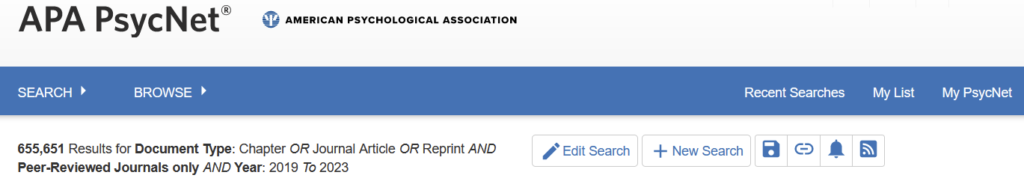

OK, challenge accepted, let’s have a look at cancer research, where the reproducibility rate of non-papermill publications is just under 12%, so we’ll round it to that figure. PubMed lists about one million papers (excluding reviews) on cancer in the last 5 years:

If the sample result of 12% were representative, this would mean that the last 5 years in cancer research produced about 880,000 unreliable publications, or about 176,000 per year. And that’s just cancer. Let’s also pick psychology, where replication rates were published as 39% in 2015. 2015 is a long time ago and psychology as a field really went to great lengths to address the practices giving rise to these low rates. Therefore, let’s assume things got better in the last decade in psychology, so after 4-5 years, maybe 50% replication was achievable. Searching for psychology articles yields about 650,000 non-review articles in the last 5 years:

This amounts to about 65,000 unreliable psychology articles per year.

So according to these very (very!) rough estimates, just the two fields of cancer research and psychology together add more than a million unreliable articles to the literature every five years or so. Clearly, those are crude back-of-the-envelope estimates, but they should be sufficient to just get an idea about the orders of magnitude we are talking about.

If the numbers hold that about 2 million articles get published every year, just these two fields would together amount to a whopping 10% of unreliable articles. Other major reproducibility projects in the social sciences and economics yield reproducibility rates in these fields of about 60%. Compare these numbers to a worst case scenario of all papermills together producing some 10k unreliable articles a year. If the scholarly literature really were a sinking boat, fighting papermills would be like trying to empty the boat with a thimble, or plug the smallest hole with a cork.

When will we finally get ourselves a new boat?

Is it fair to say that your definition of “unrealiable” includes papers of unknown reliability? That is to say if a paper cannot be replicated you class it as “unreliable” and this may encompass a range of conditions, from the true result being to opposite of that being published to the true result being as published, but with some omissions in reporting?

Hmm, yes and no.

When I use the replication rates to estimate the number of articles likely to be unreliable, I rely on the definition of the respective authors for “successful replication”. So in this case no.

However, as this is just an extrapolation, assuming the reproducibility experiments generalize to the entire field, one can’t really apply these criteria to articles for which no replication has ever been attempted. So in this case, yes, “unreliable” means that we don’t know if any particular article will replicate or not.

I only extrapolate from the samples to the entire population to make a statistical argument: if we were to test all 2 million articles of one year for their reproducibility and the extrapolation were valid, we should expect about 65k psychology articles and 176k cancer research articles to not replicate. Obviously, we won’t know which specific articles that will be, before we have done the experiments.

Did that address your question or did I misunderstand you?

Yes, you answered the question, thank you!

Comments are closed.