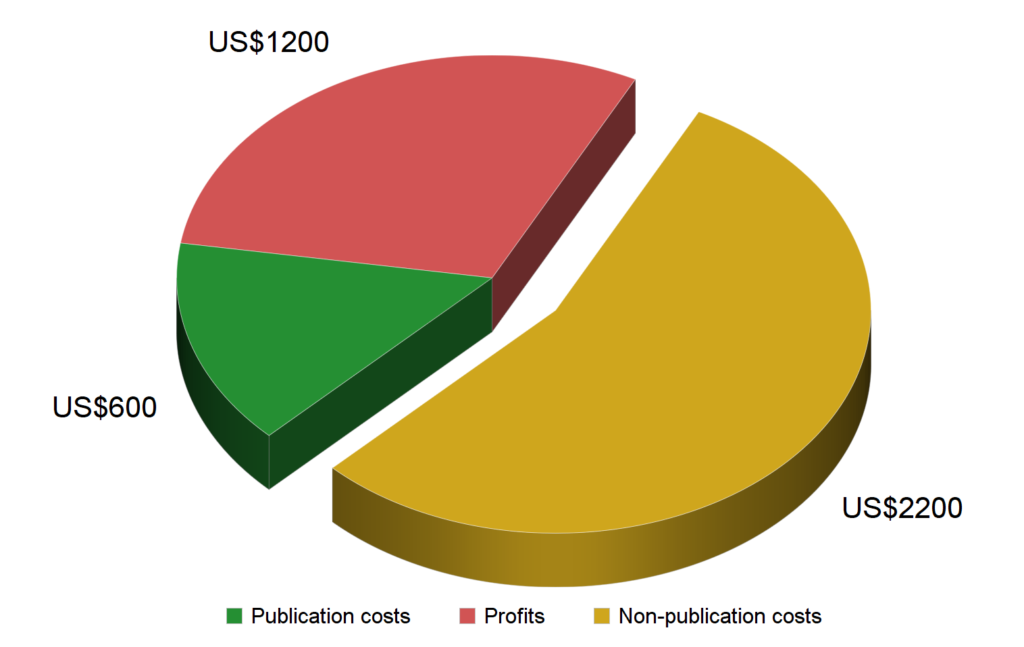

The debate over how publishers use the large “non-publication costs” (Fig. 1) that they incur and academic libraries, mainly, are funding has been going on for some time now. Above and beyond the cost items we discuss in our paper on publication costs, it has been established that investments in surveillance technology are also part of the publisher spending academic libraries are financing. In an informal brief generated by the German GFF, the legal expert who authored it describes a situation with clear indications that one cost item which we discuss in the paper has been particularly detrimental for the scholarly community and the tax payer: lobbyism.

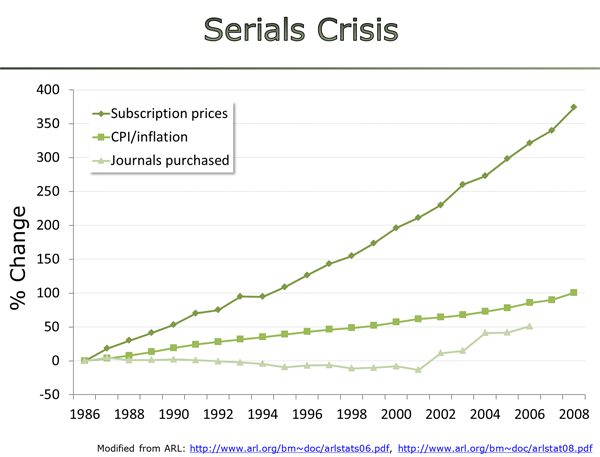

Even before Franz Inglefinger coined his eponymous rule that every scholarly article must only be published in a single journal, have scholarly journals been a collection of monopolies. Every article is only available at a single source and so there is no market and no competition. This lack of substitutability has not only been the main reason for exempting subscriptions of scholarly journals from procurement rules (“single/sole source exemption”), but of course also behind the supra-inflationary price rises to the detriment of the tax payer funding public research and teaching institutions (Fig. 2).

When the late Jon Tennant and I filed our formal complaint to the European Commission in 2018, in which we detailed how scholarly journal publishing was not a market but a collection of small monopolies, we had no idea that the EC was already well aware of that fact and saw nothing wrong with it. In fact, their reply at the time surprised us, when it indicated that the EC concurred with our description of scholarly journals being collections of monopolies, but saw levers for regulation/mitigation elsewhere.

Today, I have been privy to the informal brief written by a legal expert of the GFF mentioned above. It cites two prior EC instances from 2003 and 2015 where the EC had already acknowledged the lack of a genuine market due to the lack of substitutability (the reply to our complaint is thus just one in a long list of such documents acknowledging the lack of competition in scholarly publishing). In these documents, the EC writes, for instance:

In particular, from a demand-side point of view, it is rare that two different publications can be viewed as perfect substitutes, as there are differences in the coverage, comprehensiveness and content provided. Therefore, in terms of functional interchangeability, two different publications could hardly be regarded as substitutable by the end-users, the readers. On that basis, the Commission found that consumers will rarely substitute one publication for another following a change in their relative prices

and

Publications for different academic subjects are clearly not substitutable from the reader’s point of view. Even within a given discipline, there may be little demand side substitution from the point of view of the individual academic between different publications.

and

In this case, a strict demand approach would lead to the definition of a multitude of relevant markets of imprecise boundaries and small dimensions.

“Small dimension” of course meaning that every article would constitute its own market. The term “demand-side” here is defined as both readers, i.e., academics as well as the institutions paying for the journals, i.e., libraries, while “supply-side” refers to the publishers:

The results of the market investigation in the present case confirmed the relevance of supply-side considerations for the definition of the relevant product market in the academic publishing sector. Publications in different academic subjects are indeed not substitutable from the readers’ perspective. However, many academic publishers appear to be active across most of the possible segmentations of the market, and offer publications covering several disciplines

The quote here is an example of how the EC is well aware of the conflicting interests between readers and libraries on the one hand (demand-side) and publishers (supply-side) on the other, while at the same time expressing a clear prioritization (“confirmed the relevance”) of the interests of the supply-side over the interests of the demand-side. The dysfunctionality of the current situation for readers and libraries is understood, acknowledged and dismissed by the EC as “not relevant” – very similar to the reply we received for our formal complaint. In this particular quote, a fig-leaf is offered by stating that the big publishers cover many scholarly fields, leading to each library having contracts with several publishers, giving the superficial impression that there would be several suppliers in a “supply-side” market. The sentence just prior, however, makes it clear that this is, in fact, not really a genuine market, but one that exists only on paper, solely for regulatory purposes.

The GFF legal expert expressed his assessment that courts would be unlikely to challenge these EC market definitions as the definitions are seen as the lesser of two evils: explicit confirmation of the publisher monopolies would entail the loss of the market and with it loss of regulatory power. In other words, if the publishers were not operating within a market, they would also not be subject to regulatory market oversight. The consequence would be completely unregulated mergers between the most dominant players, which is seen as worse than the status quo.

His assessment is not changed by the “single source exemption” from procurement rules: as these rules and anti-trust regulations are separate jurisdictions, the fact that spending rules define academic publishers as monopolists while according to anti-trust regulators they are not, may be a logical contradiction, but not a legal one.

Thus, there are multiple reasons why the EC chose to merely acknowledge the interests of the scholarly community and instead define markets from the perspective of publishers. At this point, it is impossible to tell how much each reason has influenced the authors of these documents. It may not even be all that important to find this out in order to inform the scholarly community on the implications from this legal assessment. As I see it, there are two main lessons to be drawn from this legal analysis:

- If the scholarly community strives to achieve a genuine publishing market with competition, we have to design it ourselves. Politicians or other decision-makers outside of scholarship will not perform this task for us. There is not going to be any help from outside. In the lack of a clear market alternative, regulators prefer a group of relatively small monopolists over few large or even a single monopolist. The scholarly community is the only actor who can provide this missing alternative.

- Among the “non-publication costs” is a sizeable chunk of money that is being used in various legislatives around this globe to convince legislators and regulatory bodies that the interests of the academic publishing corporations outweigh the interests of the tax payer. This constitutes yet another example of how the scholarly community provides funds to publishers which then get used against the interests of the scholarly community.

From these lessons follows a clear strategic way forward: if the scholarly community wants to escape from the parasitic relationship with these corporations, it needs to create a genuine market alternative such that regulators need not fear the complete loss of market regulations. Luckily, there now are ways to create such a market and it is fully within the powers of the scholarly community to create it on its own. For this market to become a market of service providers, the scholarly content needs to come back under the control of the scholarly community. Once this market exists, the scholarly community must lobby at the relevant bodies to ensure both that “demand-side” interests receive at least the same “relevance” as “supply side” interests and that the “single source exemption” from procurement rules is annulled for scholarly publishers.

Comments are closed.