During my flyfishing vacation last year, pretty much nothing was happening on this blog. Now that I’ve migrated the blog to WordPress, I can actually schedule posts to appear when in fact I’m not even at the computer. I’m using this functionality to re-blog a few posts from the archives during the month of august while I’m away. This post is from February 17, 2012:

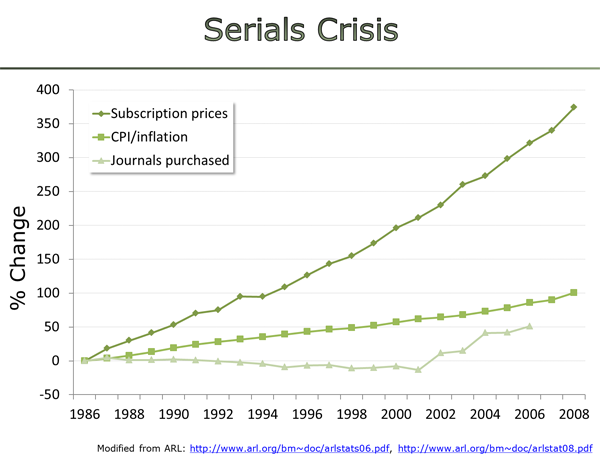

In the wake of the Elsevier boycott, some are asking if we should change our publication system and if so, how. In search for an answer to this question, I’ve been thinking about the best place to keep the works of academics safe and publicly accessible in a sustainable, long-term solution. Now what was historically the place where the work of scholars could traditionally be found? The libraries of course! However, given how entrenched some researchers are in the current way of disseminating research and given the opposition an international US$10 billion industry can muster, this solution to parasitic publishing practices is not obvious for everyone. So here I’m collecting the most obvious advantages of a library-based scholarly communication system for semantically linked literature and data.

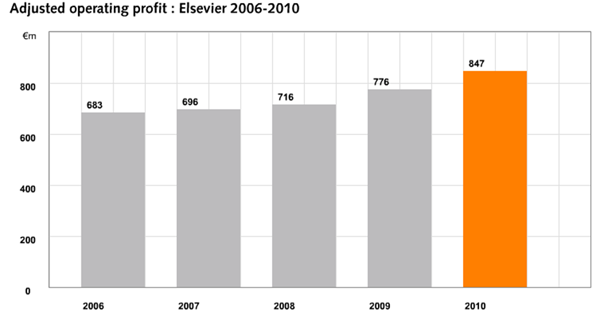

- Given a roughly 40% profit margin in academic publishing, give or take (source), the approximately US$10 billion currently being spent can be divided in 6b cost and 4b profits. If most of these funds are being spent by libraries for subscriptions, all else remaining equal, libraries stand to save about 4 billion each year if they could do the job of publishers. According to some estimates, however, costs could be dramatically lowered and thus libraries stand to save significantly more than the 4b annually. Thus, there is ample incentive for libraries and thus the tax-paying public, to cut the middleman out.

- Libraries are already debating what their future in a digital world could be. Archiving and making the work of their faculty accessible and re-usable seems like a very satisfying purpose for anyone, especially libraries discussing about how to redefine their existence.

- All the content would remain under the control of the researchers and not in the hands of private entities with diverging interests from both that of the research community and the general public.

- The funding streams for such a combined data and literature archive would be much more stable and predictable than current models, especially for long-term, sustainable database maintenance. Each university pays only actual costs in proportion to the contributions of their faculty.

- Libraries already have much of the competence to store and link data together. There are many projects on this technology (see e.g. LODUM) and plenty of research funds are being spent to further develop these technologies. Research is already going on to develop the infrastructure and tools to handle primary research data and literature at university libraries. Thus, there is not a lot that libraries really need to learn in order to do what publishers do – in fact, most libraries are already doing just that.

- Essentially, libraries are already publishers of, e.g. all the theses of their faculty or historical texts, etc. and some insitutions even have their own university/library presses. Open access to all of these digital media and many more is being organized by, e.g. National Libraries or Networked Repositories for Digital Open Access Publications. Adding scholarly articles to all that thus doesn’t really constitute a huge shift for libraries in practical terms.

- Researchers would have full control over the single search interface needed to most efficiently find the information we are looking for, instead of being stuck with several tools, each of which lacking in either coverage and features.

- It would be possible not only to implement modern semantic web technology, but also very basic functionality such as hyperlinks: clicking on “the experiments were performed as previously described” would actually take you directly to the detailed methods for the experiment.

- No more repeated reformatting when re-submitting your work.

- There still would be plenty of opportunities for commercial businesses in this sector. All the services libraries could not or would not want to do themselves can still be outsourced in a service-based, competitive commercial environment – this would not impact the usability of the scholarly corpus as in the current status quo.

- Everyone who prefers to look up numbers rather than reading the actual papers can still do that – only that the numbers provided by the new system would have an actual scientific basis. Every kind of metric we can think of is just a few lines of code away if we have full control over the format in which references to our work are handled. This allows not only assessment of articles and data, but also to create a reputation system that can be customized by the individual user to the task at hand, be it tracking topics, ranking scientists or comparing institutions.

- Users can still choose to pay ex-scientists to select what they think is the best science – after publication. In fact, then their services would actually be in competition with one another and any user’s choice wouldn’t affect others who do not share that user’s opinion on the service or their research interests.

- We easily have the funds to develop a smart tool that suggests only relevant new research papers and learns from what you and others read (and don’t read). This tool is highly customizable and suggests only the research you are interested in – and not that of other people who you haven’t chosen to do that task for you.

- The approximately 1.5 million publications still need to be published. This means few jobs would be lost and plenty of recourse would be available after a rejection. In brief, the beneficial aspects of the heterogeneity of the status quo can be conserved.

Those are only the benefits that immediately come to mind as the most important ones. Thus, as I see it, transitioning from a corporate publisher-based to a library-based system is both practically feasible in the mid-term, would eliminate many negative factors of the current system while conserving any positive values it might have had and providing many new benefits not or difficult to obtain under the current status quo. Thus, the incentives for libraries, the public and science in general are obvious. However, the incentives for individual scientists for such a transition remain small as long as journal rank determines careers. Hence, a critical factor for such a transition is to abandon journal rank in favor of more accurate metrics. I have already presented a number of publications in which the detrimental effect of journal rank has been described and I’m working with a colleague on a review paper covering all of these comprehensively.

Clearly, there will be a debate of how to best transition from the current system to a new one. In order to minimize access issues, I propose that a small set of competent and motivated libraries with large subscription budgets and substantial faculty support cooperate in taking the lead. This group of libraries would shift funds from subscriptions to investing in developing infrastructure and other components for a library-based scholarly communication system. If, say, only ten libraries cut subscriptions on the order of their ten most expensive journals, there would be more than a million Euros available every single year with little or now disruption in access. Some of the freed funds could be used to assist affected faculty in open access publication or inter-library loan of the needed articles. In this way, within a few years, the entire currently available scholarly literature could be made accessible from a single interface using tools vastly superior to the current ones (which is technically rather easy, given the low quality of what we currently have to deal with). The combination of superior access to the literature and a reduction in the requirement to publish in high-ranking journals, should provide sufficient incentives also for young researchers to support the transition.

P.S.: An often mentioned hurdle concerns the back-issues archives of the corporate publishers. Faced with a dwindling customer-base without much prospect for future involvement in scholarly communication, these companies should have little quarrels with a single fee to make all their archives accessible to libraries for transfer into the common database. Already in the current climate, extortion by holding the archives hostage, is not an option. The more we wean ourselves from these corporations, the less support they will have.

UPDATE: Heather Morrison has chimed in with one of her excellent calculations. It is high time more people are thinking along those lines, in order to develop a strategy of how to best transition towards a modern scholarly communication system.

I have an answer for The Scholarly Kitchen: because what you imagine how science works has nothing to do with reality!

I have an answer for The Scholarly Kitchen: because what you imagine how science works has nothing to do with reality! Moreover, the articles where he was single author or one of two authors are all on clinical practice and testing, raising the tentative suspicion that medical practice is really his strong area of expertise, rather than science. Which means that, again, none of these guys is actually a scientist, i.e., working in physics, chemistry, biology and regularly publishing scientific, experimental papers, which makes up the bulk of the scientific literature. If they were, they would know that there isn’t such a thing as a ‘low-quality’ scientific discovery. Scientific discoveries are like orgasms: you can’t have any bad ones. Now, I agree that there are badly conducted experiments, missing control procedures and outright fraud. None of these examples are eliminated by reducing scientific output, obviously. The authors make sure that this is not what they mean, as they refer to ‘low-quality’ science as journals or papers that aren’t cited. Obviously, hi-profile fraud cases are cited a lot. One reason for low citation counts is that very few scientists understand the topic and/or are interested in it. Clearly, this can change in a heartbeat and what was boring one day can be all the rage tomorrow. Only someone not steeped in scientific research would not be aware of that. Not surprisingly, this article has received a thorough smackdown in the comment section over there and in the

Moreover, the articles where he was single author or one of two authors are all on clinical practice and testing, raising the tentative suspicion that medical practice is really his strong area of expertise, rather than science. Which means that, again, none of these guys is actually a scientist, i.e., working in physics, chemistry, biology and regularly publishing scientific, experimental papers, which makes up the bulk of the scientific literature. If they were, they would know that there isn’t such a thing as a ‘low-quality’ scientific discovery. Scientific discoveries are like orgasms: you can’t have any bad ones. Now, I agree that there are badly conducted experiments, missing control procedures and outright fraud. None of these examples are eliminated by reducing scientific output, obviously. The authors make sure that this is not what they mean, as they refer to ‘low-quality’ science as journals or papers that aren’t cited. Obviously, hi-profile fraud cases are cited a lot. One reason for low citation counts is that very few scientists understand the topic and/or are interested in it. Clearly, this can change in a heartbeat and what was boring one day can be all the rage tomorrow. Only someone not steeped in scientific research would not be aware of that. Not surprisingly, this article has received a thorough smackdown in the comment section over there and in the