During my flyfishing vacation last year, pretty much nothing was happening on this blog. Now that I’ve migrated the blog to WordPress, I can actually schedule posts to appear when in fact I’m not even at the computer. I’m using this functionality to re-blog a few posts from the archives during the month of august while I’m away. This post is from December 28, 2012:

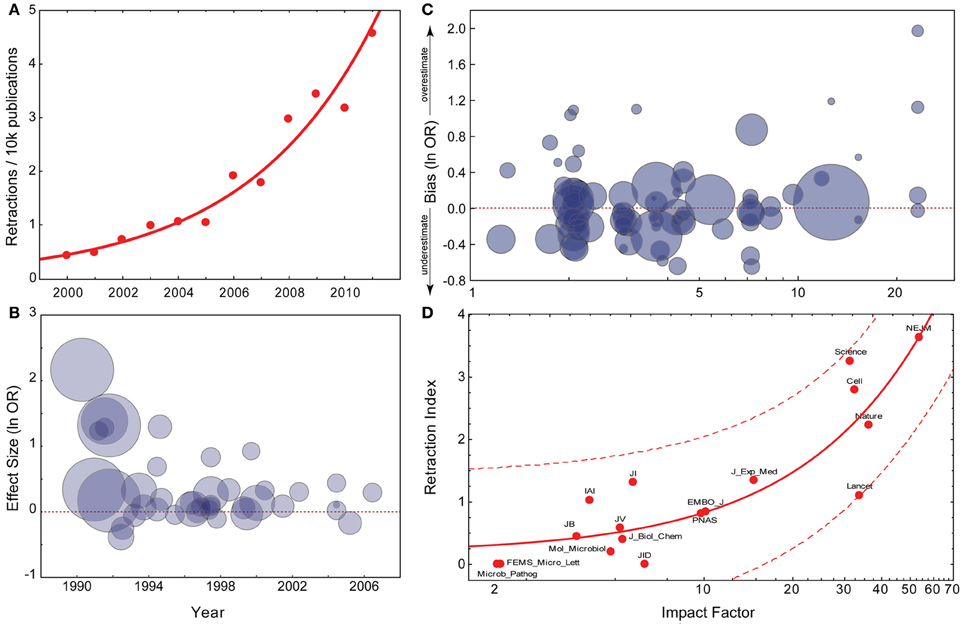

If you trust empirical evidence, science is currently heading for a cliff that makes dropping off the fiscal cliff look like a small step in comparison. As we detail in our review article currently under revision, retractions of scientific articles are increasing at an exponential rate, with the majority of retractions being caused by misconduct and fraud (but also the error-rate is increasing). The evidence suggests that journal rank (the hierarchy among the 31,000 scientific journals) contributes a pernicious incentive: because funds are tight and science is increasingly under pressure to justify its expenditure, people are rewarded for publishing in high-ranking journals. However, there is no empirical evidence that science published in these journals is any different from scientific discoveries published in other journals. If anything, high-ranking journals publish a much larger fraction of the fraudulent work than lower ranking journals and also a larger fraction of the unintentionally erroneous work. In other words, journal rank is like homeopathy, astrology or dowsing: one may have the subjective impression that there is something to it, but any such effects disappear under scientific scrutiny.

As journal rank has only been used as an instructor for the hire-and-fire policy and institutions world-wide for a few decades, the data also project some potentially catastrophic consequences of journal rank: science has been hiring those candidates who are especially good at marketing their science to top journals, but maybe not equally good at the science itself. Conversely, excellent scientists were fired who did not reach institutional requirements for marketing their research. If this is really what has been taking place, it has now been going on just long enough by now to replace an entire generation of scientists with researchers who are particularly good at marketing, providing one potential explanation of why the fraud and retraction rate is exploding just at this particular point in time. However, until a few years ago, this has been a trend that has only been observed by a few bibliometricians.

At the same time, a much more obvious trend has been receiving a lot of attention: the rising costs of acess to the scholarly literature. To counter this trend, three different publishing models have emerged, which only address the access problem, but not the parallel, and potentially underlying problem of journal rank. These models aim to provide unrestricted, open access to publicly funded research results either by charging the authors once for each article (gold), or by mandating them to place a copy not of the final PDF, but of the version approved by the referees (i.e., the version before the publishers format it) in institional repositories (green), or by providing an option for authors to make heir article accessible in a subscription journal by an additional article fee, i.e., if the authors pay the fee, their article becomes openly accessible, if not, it stays behind a paywall (hybrid). Importantly, the three models which are currently aimed at publishing reform are not sustainable in the long term:

- Gold Open Access publishing without abolishment of journal rank (or heavy regulation) will lead to a luxury segment in the market, as evidenced not only of suggested author processing charges nearing 40,000€ (US$~50,000) for the highest-ranking journals, but also by the correlation of existing author processing charges with journal rank. Such a luxury segment would entail that only the most affluent institutions or author would be able to afford publishing their work in high-ranking journals, anathema to the meritocracy science ought to be. Hence, universal, unregulated Gold Open Access is one of the few situations I can imagine that would potentially be even worse than the status quo.

- Green Open Access publishing entails twice the work on the part of the authors and needs to be mandated and enforced to be effective, thus necessitating an additional layer of bureaucracy, on top of the already unsustainable status quo.

- Hybrid Open Access publishing inflates pricing and allows publishers to not only double-dip into the public purse, but to triple-dip. Thus, Hybrid Open Access publishing is probably the most expensive version overall for the public purse.

Thus, what we have now is a status quo that is a potential threat to the entire scientific endeavor both from an access perspective and from a content perspective, and the three models being pushed as potential solutions are not sustainable, either. The need for drastic reform has never been more pressing.