In the process of migrating content from the old site to WordPress, I’m also moving some articles from there and re-publishing them here as posts. This one is such a case, originally published on December 7, 2006. Unfortunately, I never found the time to submit it to a peer-reviewed journal.

Neuroscience is predominantly interested in elucidating the effects environmental stimuli cause in our brains and how the brain transforms these stimuli into meaningful behavior. Animals including humans are thought to react with a complex combination of innate and learned “responses” to one or a set of external stimuli. However, a series of recent advances in modern behavioral neuroscience and neuroethology reminds us that freely behaving animals treat self-generated stimuli differently from other stimuli. We are always both cause and effect in the closed feedback loop between our behavior and the environment we live in. This operant loop renders the linear input/output view one-sided. The renewed interest in the biological mechanisms of

operant conditioning is the result of many years of research towards a more sophisticated view of the main function of brains.

The concept of causality is so central to the human thought process that Kant concluded it must precede all experience [1]. Our constant search for causes eventually led to the development of

religion, science and technology. In science, we look for the underlying causes of natural phenomena. Humans are also subjected to this scrutiny. The neurosciences try to understand the underlying causes for perception, disease, aging or development. In this very successful approach it is often overlooked that humans are not only responding mechanically in a cause-and-effect (stimulus-response) fashion to everything that happens to them. Humans are active agents as well and as such just as much cause as they are effect. Where does this spontaneous activity come from in a cause-and-effect world? Why is there spontaneity? Or is it just an illusion?

Early, often overlooked psychological conjecture emphasizes that spontaneous behavioral variability is a useful, as one would say today “adaptive” trait. In this article I will cite neurobiological evidence to strengthen this view. I will use a number of examples to argue that the variability measured in the behavioral performance of animals is exactly the kind of output that is required to effectively detect which of the stimuli in the incoming stream of sensory input can be controlled by the animal and which cannot. I will deliver an account as to how and why, despite its importance, this essential output-input feature of brains has largely been overlooked in recent decades. This forgotten feature is associated with a number of psychiatric disorders and only recently a new and growing trend has emerged which now provides steadily increasing understanding about the mechanisms underlying it.

Behavioral Variability: the output

We all feel the very basic notion that we possess a certain degree of freedom of choice. Bereaving humans of such freedom is frequently used as punishment and the bereft do in-variably perceive this limited freedom as undesirable. This experience of freedom is an important characteristic of what it is like to be human. It stems in part from our ability to behave variably. Voltaire expressed this intuition in saying “Liberty then is only and can be only the power to do what one will” [2]. But the concept that we can decide to behave differently even under identical circumstances underlies not only our justice systems. Electoral systems, our educational systems, parenting and basically all other social systems also presuppose behavioral variability and at least a certain degree of freedom of choice. Games and sports would be predictable and boring without our ability of constantly changing our behavior in always the same settings. Faced with novel situations, humans and most animals spontaneously increase their behavioral variability [3-5]. Inasmuch as behavioral variability between individuals has genetic components, it is a crucial factor of niche exploitation in evolution. Moreover, behavioral variability within individuals has been shown to be ecologically advantageous in game theoretical studies [6-11], in pursuit-evasion contests such as predator/prey interactions (“Protean Strategy”) [12-15], in exploration/foraging [16], in mobbing attack patterns by birds and in the variation of male songbirds’ songs [17]. Clearly, invariable behavior will be exploited [14,18] and leaves an organism helpless in unpredictable situations [19,20].

Controlling external events: the input

Thus, competitive success and evolutionary fitness of all ambulatory organisms rely critically on intact behavioral variability as an adaptive brain function. But relative freedom from environmental contingencies is a necessary, but most often not a sufficient criterion for such accomplishments. Tightly connected to the ability to produce variable behavior is the ability to use the effects of these behaviors to control the environment. The incoming stream of sensory information is noisy and fluctuates for any number of reasons. Any covariance between the behavioral variations and those of sensory input indicates that the latter are con-sequences of the behavior and can thus be controlled be the animal [21,22]. It is the on-line detection system for when the animal itself is the reason for any environmental fluctuation. This function is so paramount, that we humans express our delight over control of our environment (including other people) already as children, by e.g., shrieking in excitement when Daddy jumps after a “boo” or proudly presenting Mom with “look what I can do!”. Later, children find pleasure in building airplane models, become carpenters with a delight for shaping wood, artists feeling gratified creating art out of the simplest materials, musicians enjoying mastering their instrument to perfection, athletes, scientists, engineers or managers. Using trial and error, we have shaped our world from caves to skyscrapers, from horses to jet-planes, from spears to hydrogen bombs. Cultural or religious rituals (e.g., rain dance) and superstition may have evolved as means to create a feeling of control where ultimately there is none. Obviously, behaving flexibly in order to control our environment is at the heart of human nature and probably affects more aspects of our daily lives than any other cognitive brain function. So essential is such functioning that even very simple brains possess it. The modest fruit fly prefers a situation in which it controls its environment over one where it does not. If certain flight directions are experimentally superimposed with uncontrollable visual movements, flies quickly avoid such directions and fly only in areas of full control [23]. This experiment demonstrates that control over environmental stimuli is inherently rewarding already for simple, but more likely for all brains.

The main function of brains

The first experiments into the mechanistic basis of this basic brain function was initiated already early in the 20th century by eminent scientists like Thorndike [24], Watson [25] and Skinner [26]. Of course, the primary process by which all animals, including humans learn to control their environment is operant (or instrumental) conditioning (Box 1). Ultimately, this comparatively simple process forms one of the fundamental cornerstones not only for all of our human nature, but also for our social coherence: human nature as described in planning, willing and controlling our behavior [22,27-30] and our social coherence as based on cooperation [6,31,32]. Modern neuroscience, however, with the success of research into the mechanisms of the even simpler process of Pavlovian or classical conditioning (Box 1), has understandably shifted the focus away from the central role operant learning plays in our daily lives.

Box 1: Predictive learning

Classical (Pavlovian) conditioning is the process by which we learn the relationship between events in our environment, e.g., that lightning always precedes thunder. The most famous classical conditioning experiment involves Pavlov’s dog: The physiologist I.P. Pavlov trained dogs to salivate in anticipation of food by repeatedly ringing a bell (conditioned stimulus, CS) before giving the animals food (unconditioned stimulus, US). Dogs naturally salivate to food. After a number of such presentations, the animals would salivate to the tone alone, indicating that they were expecting the food.

Operant (instrumental) conditioning is the process by which we learn about the consequences of our actions, e.g. not to touch a hot plate. The most famous operant conditioning experiment involves the ‘Skinner-Box’ in which the psychologist B.F. Skinner (and colleagues – he mainly used pigeons himself) trained rats to press a lever for a food reward. The animals were placed in the box and after some exploring would also press the lever, which would lead to food pellets being dispensed into the box. The animals quickly learned that they could control food delivery by pressing the lever.

Both operant and classical conditioning serve to be able to predict the occurrence of important events (such as food). However, one of a number of important differences in particular suggests that completely different brain functions underlie the two processes. In classical conditioning external stimuli control the behavior by triggering certain responses. In operant conditioning the behavior controls the external events.

|

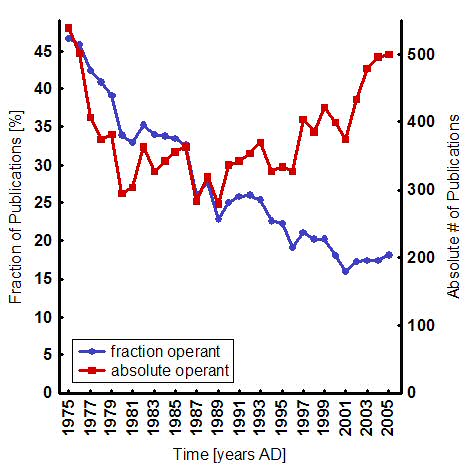

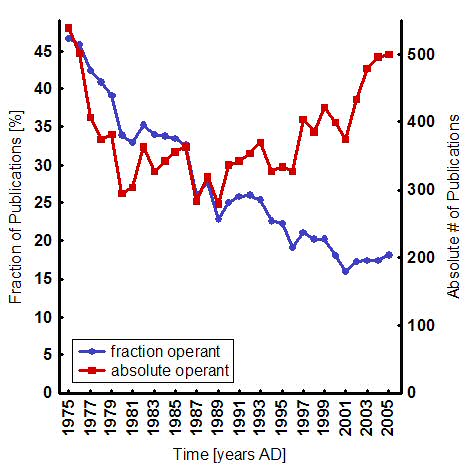

This shift is signified by a steady decrease in the fraction of biomedical publications with operant topics, despite an absolute increase of publications over the last 25 years (Fig. 1). It is an understandable shift, because nearly every learning situation seems to involve a dominant classical component anyway [33,34] and classical conditioning offers the unique advantage to quickly and easily get at the biological processes underlying learning and memory: the animals are usually restrained, leaving only few degrees of freedom and the stimuli can be traced to the points of convergence where the learning has to take place. The neurobiological study of classical conditioning, pioneered by Nobel laureate Eric Kandel, was the first avenue into some of the biological mechanisms of general brain function. Today, overwhelmed by the amazing progress in the past three decades, some neuroscientists even ponder reducing general brain function almost exclusively (“95%”) to classical stimulus-response relationships, with profound implications for society, in particular for the law [35,36]. The Dana Foundation, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Civil Liberties Union have already sponsored meetings on these implications [37,38]. Stretching the generality of such awesome classical conditioning paradigms as fear conditioning in rats and mice [39], rabbit eyeblink conditioning [40] or classical conditioning of the Aplysia gill withdrawal reflex [41], the current neuroscientific standard implies that they are all-encompassing paradigms for general cognitive brain function: “brain function is ultimately best understood in terms of input/output transformations and how they are produced” [42].

Fig.1: Publishing development of publications on operant conditioning. The graph shows a steady decline in the fraction of publications dealing with operant conditioning (blue) despite an increase in absolute number of publications over the last 25 years (red). Note the increase in the last four years. Absolute numbers were gathered by running an NCBI PubMed query “((operant OR instrumental) AND (conditioning OR learning))” (red). This number was divided by the number of publications containing only “conditioning”, to derive a percentage (blue). Notice the sharp jump in the absolute number for the last five years. This jump is even noticeable in the relative contributions. |

It is rarely recognized that, at an adaptive level, cognitive capacities, such as those involved in encoding the predictive relations between stimuli, can be of little functional value to a hypothetical, purely Pavlovian organism. For instance, one can imagine any number of situations which require the animal to modify, even to withhold or reverse, the direction of some behavior in order to solve the situation. Such situations demand greater behavioral flexibility than the system mediating classical conditioning provides. Moreover, using the re-afference principle [43-45], operant behavior underlies the distinction between observing and doing, i.e. differentiating between self and non-self. We compare our behavioral output (efference) with incoming sensory input (afference) to detect when we are the ones authoring environmental change [21,22]. One almost iconographic example of such behavior is to per-form various spontaneous movements in front of a mirror to detect whether it is us we are perceiving [46,47]. This automatic detection-mechanism explains why we cannot tickle our-selves [21], why we perceive a stable visual world despite our frequent quick, or saccadic, eye movements [48] and is reflected in different brain activation patterns between self-generated and exogenous visual stimulation [49]. It is thought that the detection is accomplished via an efference copy (or corollary discharge) of the motor command which is compared to incoming afferent signals to distinguish re-afference from ex-afference. Such a differentiation has been implied to demonstrate causal reasoning in rats [50,51]. Even robots can use such “self-modeling” to generate a continuously updated model of themselves and their environment [52]. Conspicuously, the organization of the brain also raises doubts about the input/output mainstream image. Less than 10% of all synapses in the brain carry incoming sensory information and as little as 0.5-1% of the brain’s total energy budget are sufficient to handle the momentary demands of the environment [53]. In other words, input/output transformations may only account for a small fraction of what brains are doing. Maybe a much more significant portion of the brain is occupied with the ongoing modeling of the world and how it might react to our actions? Recent evidence suggests that the brain predicts the sensory consequences of motor commands because it integrates its prediction with the actual sensory information to produce an estimate of sensory space that is enhanced over predictions from either source alone [54]. This effect of operant enhancement of sensory cues can be observed also in fruit fly learning [23,34] and may explain why starlings, but not tamarin monkeys can recognize patterns defined by so-called recursive grammar [55]. Such control of sensory input has often been termed “goal-directed” behavior. This perspective provides an intuitive under-standing of the rewarding properties of being in control of the environment. Setting and obtaining goals is inherently rewarding [56]. This reward ensures that individuals always actively strive to control.

At the same time, by controlling the environmental input using operant feedback loops, individuals exert their effect not only on themselves, but their survival and procreation in the environment they create for themselves directly affects

evolution. This has been shown in the field, e.g., for western bluebirds, which dissociate into different niches ac-cording to their level of aggression [57]. Another example are small-brained prey being more likely to be caught by predators, presumably because their capacity for behavioral variability is also smaller [15]. In humans such mechanisms have been proposed to explain otherwise hard to understand phenomena such as high IQ heritability estimates and associated paradoxes (i.e., increasing IQ heritability with age/experience and the “Flynn-Effect” of increasing IQ over generations) [58,59]. Expecting sensory feedback signals can go so far that willing to move a limb can lead to the illusion of limb movement, even if none occurred [60]. One may say that we so want our actions to have an effect that we sometimes even develop a bad con-science even though we have not done anything wrong. Considering the operant feedback loop between initiating behavioral variability and the continuous prediction/evaluation of the environmental stimuli under behavioral control, it becomes clear that brain function can probably be understood just as well in terms of output/input transformations as the other way around. Deciding which output to produce in the next moment in order to control sensory input is the central organizing principle of brains [61]. Only through developing an understanding of the neural bases of operant learning, will we come to a full biological understanding of this principle.

Far-reaching implications

This evidence indicates that our behavior consists at least as much of goal-directed actions as it consists of responses elicited by external stimuli. But not all stimulus-response contingencies are acquired by classical conditioning. Goal-directed actions can become partially independent of their environmental feedback and develop into habits controlled mainly by antecedent stimuli [62-64]. Everybody has experienced such ‘slip of action’ instances, when we take the wrong bus home days after we have moved, when we keep reaching for the wrong buttons or levers in our new car, when we try to open our home door with the work keys or when we take the freeway-exit to our workplace, even though we were heading for the family retreat. William James [65] is often quoted as claiming that “very absent-minded persons in going in their bedroom to dress for dinner have been known to take of one garment after an-other and finally to get into bed, merely because that was the habitual issue of the first few movements when performed at a late hour”.

Habits or rituals are important for efficiently carrying out often-repeated behaviors by limiting the amount of behavioral variability. The degree to which classical responses or operant habits/rituals limit the behavioral variability can also be used to gauge mental health. A range of psychiatric disorders share the symptoms of reduced behavioral variability, in severe cases even behavioral rituals or stereotypies (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, obsessive com-pulsive disorder, depression [17]). Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies provide a potential mechanistic basis for these cases: Negative behavioral consequences mimic depression in that they tend to inhibit cortical premotor-areas. This inhibition is sensitive to psycho-logical therapy [66]. On the other hand, individuals diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder are reported to have increased behavioral variability. Being able to flexibly produce the right amount of behavioral variability under any given circumstance is not only a prerequisite for controlling our environment, but appears to also be a key marker for psychological health. It fits very well into the concept of producing behavioral variability to control our environment that patients with psychiatric depression also often report a lack of control of their lives. The dysfunctional behaviors of animals and people deprived of the opportunity to control their environments are common knowledge, e.g., the self-injury and cage stereotypies of solitary animals, and the depressing, dispiriting effects of living on welfare. “Learned helplessness” is a standard animal model for depression in which animals become depressed by exposure to uncontrollable shocks [67]. The degree of control over such stress-ors is critical for the development of depression. In rats, the infralimbic and prelimbic regions of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex detect whether the stressor is under operant control and suppress the depression-inducing effects the stressor would have without operant control [68]. The ventral medial prefrontal cortex is part of a prefrontal-basal ganglia-cortical feedback system thought to be involved in motor selection and control [62]. In humans, control of painful stimuli exerts an analgesic effect which appears to rely on the anterolateral prefrontal cortex [69]. Operant control is even said to slow the cognitive decay occurring in patients when they enter the late stage of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease), a degenerative motorneuron disorder [70]. Anorexic patients often report that controlling their eating and hunger is the only means of control left in their lives. Often these patients, when they eat, always cut the food into the same number of pieces and chew them for the same number of times. Anorexia nervosa and obsessive compulsive disorder share this symptom of rituals/stereotypies and show a high degree of comorbidity [71]. Patients with obsessive compulsive disorder show hyperactivity in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in on-line behavioral evaluation and detection of negative behavioral consequences [72-74]. The anterior cingulate is also part of the prefrontal-basal ganglia-cortical feedback system.

Apart from overt behavior, the degree to which we feel in control also influences cognitive performance [75]. The need to feel in control drives some people to seek excessively to master novel situations. These “novelty seekers” are known for their vulnerability to develop an addiction to drugs of abuse [76]. It appears that the same midbrain dopamine neurons which are thought to mediate reward [77-80] also mediate the stimulating effects of novelty [5]. This aspect has received particular attention with the majority of studies involving oper-ant conditioning being concerned with the mechanisms of addiction. In these paradigms, ad-diction is modeled by training animals to perform actions in order to obtain drugs until the actions have become habits, i.e. independent of their consequences. This situation mimics the failure of the negative consequences of addiction to exert any significant effect on the drug-taking habit.

But

operant conditioning is also the paradigm of choice to model the production of flexible behavior often compromised in a number of other medical conditions. Complementing the deficits in behavioral variability and control cited above, other symptoms particularly in neuropathologies involving higher-order cognitive or executive functions as well as, more generally, the impact of emotional and motivational dysfunction in a range of syndromes, indicate the widespread relevance of operant mechanisms. For example, neuropsychological studies have established a connection between various compromised prefrontal-subcortical circuits and deficits associated with executive function in humans [27-29,81]. Deficits in ex-ecutive function have been generally described as comprising multiple components usually including volition, planning, purposive action and effective performance [30] and so signifi-cant operant involvement can be expected. Over and above specific deficits in behavioral choice and motor control, executive dysfunction has also been found in a range of neurode-generative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease. The early onset of many of the executive dysfunctions associated with these disorders suggests that even motor deficits involving tremor and choreic symptoms may partially reflect a disorder in the sustained functioning of the pre-frontal-basal ganglia-cortical feedback system during planning, decision making and behavior initiation [82]. In contrast, patients with Tourette’s syndrome show enhanced executive control, dissociating cognitive (frontal, medio-frontal) from non-cognitive control (subcortical, where the tics are assumed to be initiated) [81]. Interestingly, bilingual children also show enhanced cognitive control.

The experience of willing to do something and then successfully doing it is absolutely central to developing a sense of who we are (and who we are not) and that we are in control (and not being controlled). This sense is compromised in patients with dissociative identity disorder, alien hand syndrome, or schizophrenic delusions [21]. In some of these disorders the abovementioned midbrain dopamine neurons appear to play a central role, tying, e.g., Parkinson and schizophrenia tightly to operant models. Parkinson’s patients are administered the dopamine precursor L-DOPA, while schizophrenics are treated with a group of antipsychotics, most of which target and inhibit the D2 dopamine receptor. Some of these antipsychotic drugs have Parkinson-like side-effects. Recent research shows that L-DOPA and the antipsychotic haloperidol have opposite effects on operant decision-making in humans [83]. One is tempted to interpret these data as evidence for the hypothesis that the overlapping and interacting dopaminergic systems mediating primary rewards such as food, water or sex and those mediating behavior initiation and control are so tightly inter-connected precisely because of the rewarding properties of controlling the environment with behavior. As information such as the above accumulates, elucidating the mechanisms of

operant conditioning becomes more and more promising as an avenue into understanding the causality underlying disorders such as those described above and their treatment.

There may even be a wider prospect of the study of

operant conditioning. Many of the abovementioned disorders show a gender-specific pattern of occurrence. For example, depression, anorexia and obsessive compulsive disorder show a higher prevalence in women than in men, while autism, addiction and Tourette’s syndrome are more common in men then in women. A recent study has shown the male striatum to release up to 3 times more dopamine when stimulated by amphetamine, than in females [84]. It is conceivable that such a gender-difference in the processing of appetitive and aversive stimuli may be the underlying factor influencing the gender-specificity of many psychiatric disorders, which can be modeled by

operant conditioning paradigms.

Scarce but converging biological data

Compared to its significance, our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying operant conditioning is rather vague. The more important is a recent swell of ground-breaking studies (see also Fig. 1). A number of different model systems have contributed to this progress on various levels of operant conditioning. I will try to integrate the knowledge gained from such disparate sources to describe the general picture as it is currently emerging.

Conceptually, the mechanism underlying

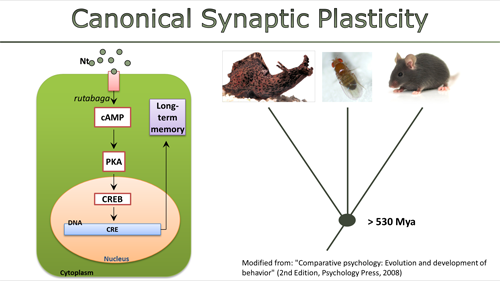

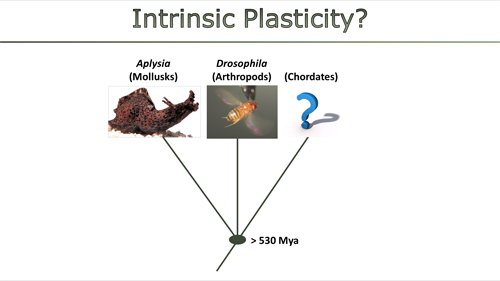

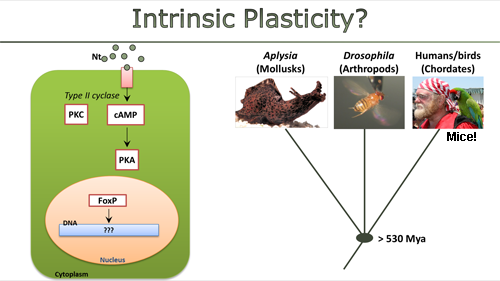

operant conditioning appears to consist of two modules: one is concerned with generating variable behavior and another predicts and evaluates the consequences of this behavior and feeds back onto the initiation stage [85-87]. Evidence from imaging humans suggests that dorsal and ventral striatum, respectively, may represent circuits involved each in one of the modules [87]. There is only very poor biological knowledge about the first module. Behavioral variability could be generated actively by dedicated circuits in the brain [12,14,88] or simply arise as a by-product of accumulated errors in an imperfectly wired brain (“neural noise” [89-92]). Despite recent evidence supporting the neural control of behavioral variability [9,17,93], the question remains controversial. Only little more is known about the neurobiology of the second module. Promising potential mechanisms have recently been reported from humans [21], rats [94], crickets [95] and Aplysia [96]. These studies describe neural pathways for re-afferent evaluation of behavioral output (via efference copies) and potential cellular mechanisms for the storage of the results of such evaluations. However, to this date, a general unifying principle such as that of synaptic plasticity in

classical conditioning is still lacking. But with Eric Kandel joining the swell with new

operant conditioning paradigm for

Aplysia gill withdrawal [97], one can speculate that we may well be on the verge of a genuine paradigm shift in the neurosciences.

From a larger perspective, there is early evidence suggesting that the traditional distinction into operant and

classical conditioning needs to be reconsidered. It appears that an experimental separation of classical and operant components is essential for the study of associative learning. Most associative learning situations comprise components of both behavioral (operant) and sensory (classical) predictors (composite conditioning). For example, if we touch a hot plate, we learn both about the plate and about our touch. If a frog attempts to catch a bee with its tongue, it can learn both about the striped insect and about extending its tongue towards it. If a rat in a Skinner-Box presses the lever for a food reward, it learns both about pressing the lever and about a depressed lever indicating food.

Research primarily from

Drosophila and

Aplysia has succeeded in eliminating much if not all of the classical component in ‘pure’

operant conditioning experiments [34,98-101]. This type of

operant conditioning appears more akin to habit formation and seems to lack an extended goal-directed phase. The same studies also revealed that such pure

operant conditioning (maybe better termed “

self-learning”) differs from

classical conditioning (more parsimoniously called “world-learning”) on the molecular level. While world-learning acts via a type I adenylyl cyclase that is regulated by Ca2+/Calmodulin and G protein, the evidence points towards self-learning as being based on a dopamine receptor-coupled type II adenylyl cyclase which eventually leads to the activation of dopamine and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-regulated phosphoprotein, 32 kDa – DARPP-32, which is involved in a variety of processes and disorders associated with operant functioning in vertebrates [102-104]. The research implies that the acquisition of skills and habits, such as writing, driving a car, tying laces or our going to bed rituals is not only processed by different brain structures than our explicit memories, the neurons also use different biochemical processes to store these memories. If these early results were substantiated, classical conditioning paradigms cannot serve as the general tools for all learning and memory research as they do today.

The realization that composite conditioning consists of separable self-learning and world-learning components opens the possibility to observe the interactions between them [23,34]. For instance, the early, goal-directed phase is dominated by world-learning which is facilitated by allowing a behavior to control the stimulus about which the animal learns. Self-learning in this phase is suppressed by the world-learning mechanism. If training is extended, this suppression can be overcome and a habit can be formed. Organizing these processes in such a hierarchical way safeguards the organism against premature stereotypization of its behavioral repertoire and allows such behavioral stereotypes only if they provide a significant advantage. This insight supports early hypotheses about dominant classical components in operant conditioning [33], but only for the early, goal-directed phase.

These results may have drastic implications for all learning experiments: as soon as the behavior of the experimental subject has an effect on its subsequent stimulus situation, different processes seem to be at work than in experiments where the animal’s behavior has no such consequences, even if the subject in both cases is required to only learn about external stimuli. The hierarchical organization of fact- and skill-learning processes also explains why we sometimes have to train so hard to master certain skills and why it sometimes helps to shut out dominant visual stimuli by closing our eyes when we learn them. Gene expression analysis in vertebrates supports the separation of these two components: goal-directed phases of learning are characterized by immediate-early gene expression in the frontal and cingulate cortices, whereas later, habitual phases are characterized by gene expression in the ventrolateral striatum [63,64].

As mentioned above, midbrain dopamine neurons are considered to be the main mediators of reward in vertebrates[77-80]. Given the prominent status of input/output transformations in the brain, it is not surprising that the role of dopamine signaling has always been described in the context of prediction errors triggered by external stimuli. Only now has a re-thinking begun and a new hypothesis has emerged which challenges this view and instead suggests a prominent role of the short latency dopamine signal in output/input computations [105]. Recent brain imaging evidence points towards the medial orbitofrontal cortex as a component downstream of this dopamine signal. When controlling the environment with behavior, this brain area shows activation both to obtained rewards and to successfully avoided punishments [56].

Another case for multiple model systems

Our relative lack of knowledge stems in part from research into operant conditioning being conceptually much more challenging than classical conditioning. However, recent progress in invertebrate neuroscience suggests that the now classic Kandelian approach of relying heavily on simpler brains while developing tools and models for vertebrate research is even more promising today in the age of advanced molecular, genetic, imaging and physiological repertoires in invertebrates than 30 years ago [20,106]. Even in the post-genomic era, invertebrate models offer the possibility to rapidly and effectively learn about important principles and molecules which can then be used to reduce the complexity of the vast vertebrate brain [107]. Besides offering a more effective avenue into studying the neural basis of operant conditioning, such an integrative approach will provide us with insights into the exciting question of why invertebrate and vertebrate brains are structurally so very different even though the basic demands of life are quite similar in both groups. Moreover, a multi-faceted approach will allow us to distinguish general mechanisms from species-specific adaptations. Coincidentally, using multiple model systems effectively reduces the number of vertebrate experimental animals, working towards the ‘3R’ goals — refinement, reduction and replacement [108]. Combining the rapid technical advancements also in vertebrate physiology, imaging and behavior [109] with modern computational power, neuroscience is now more than ready to finally tackle operant conditioning on a broad scale. The recent swell of publications on operant conditioning is the logical consequence of 20 years of meticulous research during the dominant input/output mainstream [62]. The most important questions to be answered in future research are:

- What are the brain-circuits generating spontaneous behavior?

- How is sensory feedback integrated into these circuits?

- Which are the ‘operant’ genes?

- What are the mechanisms by which fact-learning suppresses skill-learning?

- How can repetition overcome this suppression?

Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Bernd Grünewald, Bernhard Komischke, Gérard Leboulle, Diana Pauly, John Caulfield, Peter Wolbert, Martin Heisenberg and Randolf Menzel for critically reading an earlier version of the manuscript. I am especially indebted to Bernard Balleine and Charles Beck for providing encouragement, stimulating information and some key references.

References:

1. Kant I (1781) Critique of Pure Reason: NuVision Publications, LLC. 444 p.

2. Voltaire (1752/1924) Voltaire’s philosophical dictionary. Wolf HI, translator. New York, NY, USA: Knopf.

3. Shahan TA, Chase PN (2002) Novelty, stimulus control, and operant variability. Behavior Analyst 25: 175-190.

4. Roberts S, Gharib A (2006) Variation of bar-press duration: Where do new responses come from? Behavioural Processes

Proceedings of the Meeting of the Society for the Quantitative Analyses of Behavior – SQAB 2005 72: 215-223.

5. Bunzeck N, Duzel E (2006) Absolute Coding of Stimulus Novelty in the Human Substantia Nigra/VTA. Neuron 51: 369-379.

6. McNamara JM, Barta Z, Houston AI (2004) Variation in behaviour promotes cooperation in the Prisoner’s Dilemma game. Nature 428: 745-748.

7. Glimcher P (2003) Decisions, uncertainty, and the brain: the science of neuroeconomics. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

8. Glimcher PW, Rustichini A (2004) Neuroeconomics: the consilience of brain and decision. Science 306: 447-452.

9. Glimcher PW (2005) Indeterminacy in brain and behavior. Annu Rev Psychol 56: 25-56.

10. Platt ML (2004) Unpredictable primates and prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 7: 319-320.

11. Brembs B (1996) Chaos, cheating and cooperation: Potential solutions to the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Oikos 76: 14-24.

12. Grobstein P (1994) Variability in behavior and the nervous system. In: Ramachandran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. New York: Academic Press. pp. 447-458.

13. Driver PM, Humphries N (1988) Protean behavior: The biology of unpredictability. Ox-ford, England: Oxford University Press.

14. Miller GF (1997) Protean primates: The evolution of adaptive unpredictability in competition and courtship. In: Whiten A, Byrne RW, editors. Machiavellian Intelligence II: Extensions and evaluations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 312-340.

15. Shultz S, Dunbar R (2006) Chimpanzee and felid diet composition is influenced by prey brain size. Biology Letters: FirstCite.

16. Belanger JH, Willis MA (1996) Adaptive control of odor-guided locomotion: Behavioral flexibility as an antidote to environmental unpredictability. Adaptive Behavior 4: 217-253.

17. Neuringer A (2004) Reinforced variability in animals and people: implications for adaptive action. Am Psychol 59: 891-906.

18. Jablonski PG, Strausfeld NJ (2001) Exploitation of an ancient escape circuit by an avian predator: relationships between taxon-specific prey escape circuits and the sensitivity to visual cues from the predator. Brain Behav Evol 58: 218-240.

19. Heisenberg M (1994) Voluntariness (Willkürfähigkeit) and the general organization of behavior. Life Sciences Research Report 55: 147-156.

20. Greenspan RJ (2005) No Critter Left Behind: An Invertebrate Renaissance. Current Biology 15: R671-R672.

21. Bays PM, Flanagan JR, Wolpert DM (2006) Attenuation of Self-Generated Tactile Sensations Is Predictive, not Postdictive. PLoS Biology 4: e28.

22. Wegner DM (2002) The illusion of conscious will. Boston: Bradford Books/MIT press. 419 p.

23. Heisenberg M, Wolf R, Brembs B (2001) Flexibility in a single behavioral variable of Drosophila. Learn Mem 8: 1-10.

24. Thorndike EL (1911) Animal Intelligence. New York: Macmillan.

25. Watson J (1928) The ways of behaviorism. New York: Harper & Brothers Pub.

26. Skinner BF (1938) The behavior of organisms. New York: Appleton.

27. Owen AM (1997) Cognitive planning in humans: neuropsychological, neuroanatomical and neuropharmacological perspectives. Prog Neurobiol 53: 431-450.

28. Frith CD, Friston K, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RS (1991) Willed action and the prefrontal cortex in man: a study with PET. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 244: 241-246.

29. Knight RT, Grabowecky MF, Scabini D (1995) Role of human prefrontal cortex in attention control. Adv Neurol 66: 21-34; discussion 34-26.

30. Lezak MD (1995) Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 1056 p.

31. Gutnisky DA, Zanutto BS (2004) Cooperation in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma is learned by operant conditioning mechanisms. Artificial Life 10: 433-461.

32. Sanabria F, Baker F, Rachlin H (2003) Learning by pigeons playing against tit-for-tat in an operant prisoner’s dilemma. Learn Behav 31: 318-331.

33. Rescorla RA (1987) A Pavlovian analysis of goal-directed behavior. American Psychologist 42: 119-129.

34. Brembs B (2006, subm.) Hierarchical interactions facilitate Drosophila predictive learning. Neuron.

35. Greene J, Cohen J (2004) For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 359: 1775-1785.

36. Weigmann K (2005) Who we are. EMBO Rep 6: 911-913.

37. Garland B, Glimcher PW (2006) Cognitive neuroscience and the law. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 16: 130-134.

38. Garland B (2004) Neuroscience and the Law: Brain, Mind, and the Scales of Justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

39. LeDoux JE (2000) Emotion Circuits in the Brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience 23: 155-184.

40. Medina JF, Christopher Repa J, Mauk MD, LeDoux JE (2002) Parallels between cerebellum- and amygdala-dependent conditioning. Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 122-131.

41. Kandel ER (2001) The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science 294: 1030-1038.

42. Mauk MD (2000) The potential effectiveness of simulations versus phenomenological models. Nat Neurosci 3: 649-651.

43. Todorov E (2004) Optimality principles in sensorimotor control. Nat Neurosci 7: 907-915.

44. von Holst E, Mittelstaedt H (1950) Das Reafferenzprinzip. Wechselwirkungen zwischen Zentralnervensystem und Peripherie. Naturwissenschaften: 464-476.

45. Webb B (2004) Neural mechanisms for prediction: do insects have forward models? Trends Neurosci 27: 278-282.

46. Plotnik JM, de Waal FBM, Reiss D (2006) Self-recognition in an Asian elephant. PNAS 103: 17053-17057.

47. Reiss D, Marino L (2001) Mirror self-recognition in the bottlenose dolphin: A case of cognitive convergence. PNAS 98: 5937-5942.

48. Sommer MA, Wurtz RH (2006) Influence of the thalamus on spatial visual processing in frontal cortex. Nature advanced online publication.

49. Matsuzawa M, Matsuo K, Sugio T, Kato C, Nakai T (2005) Temporal relationship be-tween action and visual outcome modulates brain activation: an fMRI study. Magn Reson Med Sci 4: 115-121.

50. Blaisdell AP, Sawa K, Leising KJ, Waldmann MR (2006) Causal Reasoning in Rats. Science 311: 1020-1022.

51. Clayton N, Dickinson A (2006) Rational rats. Nat Neurosci 9: 472-474.

52. Bongard J, Zykov V, Lipson H (2006) Resilient Machines Through Continuous Self-Modeling. Science 314: 1118-1121.

53. Raichle ME (2006) NEUROSCIENCE: The Brain’s Dark Energy. Science 314: 1249-1250.

54. Vaziri S, Diedrichsen J, Shadmehr R (2006) Why Does the Brain Predict Sensory Consequences of Oculomotor Commands? Optimal Integration of the Predicted and the Ac-tual Sensory Feedback. J Neurosci 26: 4188-4197.

55. Marcus GF (2006) Language: Startling starlings. Nature 440: 1117-1118.

56. Kim H, Shimojo S, O’Doherty JP (2006) Is Avoiding an Aversive Outcome Rewarding? Neural Substrates of Avoidance Learning in the Human Brain. PLoS Biology 4: e233.

57. Duckworth R (2006) Aggressive behaviour affects selection on morphology by influencing settlement patterns in a passerine bird. Proc R Soc Lond B: FirstCite.

58. Dickens WT, Flynn JR (2001) Heritability estimates versus large environmental effects: the IQ paradox resolved. Psychol Rev 108: 346-369.

59. Toga AW, Thompson PM (2005) Genetics of brain structure and intelligence. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 1-23.

60. Gandevia SC, Smith JL, Crawford M, Proske U, Taylor JL (2006) Motor commands contribute to human position sense. J Physiol (Lond) 571: 703-710.

61. Gintis H (2006, in press) A Framework for the Unification of the Behavioral Sciences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

62. Yin HH, Knowlton BJ (2006) The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 464-476.

63. Hernandez PJ, Schiltz CA, Kelley AE (2006) Dynamic shifts in corticostriatal expression patterns of the immediate early genes Homer 1a and Zif268 during early and late phases of instrumental training. Learn Mem 13: 599-608.

64. Aragona BJ, Carelli RM (2006) Dynamic neuroplasticity and the automation of motivated behavior. Learn Mem 13: 558-559.

65. James W (1890) The Principles of Psychology. New York: Holt.

66. Davis H. fMRI Bold Signal changes in Athletes in response to video review of failure: Effects of cognitive reappraisal (CBT). 2006; San Francisco.

67. Seligman M (1975) Helplessness: On depression, development, and death.: W. H. Free-man.

68. Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, et al. (2005) Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nat Neurosci 8: 365-371.

69. Wiech K, Kalisch R, Weiskopf N, Pleger B, Stephan KE, et al. (2006) Anterolateral Pre-frontal Cortex Mediates the Analgesic Effect of Expected and Perceived Control over Pain. J Neurosci 26: 11501-11509.

70. Birbaumer N (2006) Breaking the silence: Brain-computer interfaces (BCI) for communication and motor control. Psychophysiology 43: 517-532.

71. Steinglass J, Walsh BT (2006) Habit learning and anorexia nervosa: A cognitive neuroscience hypothesis. Int J Eat Disord.

72. Taylor SF, Martis B, Fitzgerald KD, Welsh RC, Abelson JL, et al. (2006) Medial Frontal Cortex Activity and Loss-Related Responses to Errors. J Neurosci 26: 4063-4070.

73. Magno E, Foxe JJ, Molholm S, Robertson IH, Garavan H (2006) The Anterior Cingulate and Error Avoidance. J Neurosci 26: 4769-4773.

74. Somerville LH, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM (2006) Anterior cingulate cortex responds differentially to expectancy violation and social rejection. 9: 1007-1008.

75. Miller LS, Lachman ME (1999) The sense of control and cognitive aging: Toward a model of mediational processes.. In: Blanchard-Fields F, Hess T, editors. Social cogni-tion. New York: Academic Press. pp. 17–41.

76. Bardo MT, Donohew RL, Harrington NG (1996) Psychobiology of novelty seeking and drug seeking behavior. Behavioural Brain Research 77: 23-43.

77. Schultz W (2005) Behavioral Theories and the Neurophysiology of Reward. Annu Rev Psychol.

78. Schultz W (2001) Reward signaling by dopamine neurons. Neuroscientist 7: 293-302.

79. Schultz W (2002) Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron 36: 241-263.

80. Schultz W, Dickinson A (2000) Neuronal coding of prediction errors. Annu Rev Neurosci 23: 473-500.

81. Mueller SC, Jackson GM, Dhalla R, Datsopoulos S, Hollis CP (2006) Enhanced Cognitive Control in Young People with Tourette’s Syndrome. Current Biology 16: 570-573.

82. Brown P, Marsden CD (1999) Bradykinesia and impairment of EEG desynchronization in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 14: 423-429.

83. Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Frith CD (2006) Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. 442: 1042-1045.

84. Munro, McCaul, Wong, Oswald, Zhou, et al. (2006) Sex Differences in Striatal Dopamine Release in Healthy Adults. Biological Psychiatry 59: 966-974.

85. Dayan P, Balleine BW (2002) Reward, motivation, and reinforcement learning. Neuron 36: 285-298.

86. Wolf R, Heisenberg M (1991) Basic organization of operant behavior as revealed in Drosophila flight orientation. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology 169: 699-705.

87. O’Doherty J, Dayan P, Schultz J, Deichmann R, Friston K, et al. (2004) Dissociable roles of ventral and dorsal striatum in instrumental conditioning. Science 304: 452-454.

88. Krechevsky I (1937) Brain mechanisms and variability II. Variability where no learning is involved. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 23: 139-160.

89. McCormick DA (1999) Spontaneous Activity: Signal or Noise? Science 285: 541-543.

90. Lum CS, Zhurov Y, Cropper EC, Weiss KR, Brezina V (2005) Variability of swallowing performance in intact, freely feeding Aplysia. J Neurophysiol 94: 2427-2446.

91. de Ruyter van Steveninck RR, Lewen GD, Strong SP, Koberle R, Bialek W (1997) Reproducibility and Variability in Neural Spike Trains. Science 275: 1805-1808.

92. Gilden DL, Thornton T, Mallon MW (1995) 1/f noise in human cognition. Science 267: 1837-1839.

93. Maye A, Hsieh C, Sugihara G, Brembs B (2006, in prep.) Order in spontaneous behavioral activity in Drosophila.

94. Reynolds JNJ, Hyland BI, Wickens JR (2001) A cellular mechanism of reward-related learning. Nature 413: 67-70.

95. Poulet JFA, Hedwig B (2006) The Cellular Basis of a Corollary Discharge. Science 311: 518-522.

96. Brembs B, Lorenzetti FD, Reyes FD, Baxter DA, Byrne JH (2002) Operant reward learning in Aplysia: neuronal correlates and mechanisms. Science 296: 1706-1709.

97. Hawkins RD, Clark GA, Kandel ER (2006) Operant Conditioning of Gill Withdrawal in Aplysia. J Neurosci 26: 2443-2448.

98. Baxter DA, Byrne JH (2006) Feeding behavior of Aplysia: A model system for comparing cellular mechanisms of classical and operant conditioning. Learning and Memory 13: 669-680.

99. Putz G, Bertolucci F, Raabe T, Zars T, Heisenberg M (2004) The S6KII (rsk) gene of Drosophila melanogaster differentially affects an operant and a classical learning task. J Neurosci 24: 9745-9751.

100. Lorenzetti FD, Mozzachiodi R, Baxter DA, Byrne JH (2006) Classical and operant conditioning differentially modify the intrinsic properties of an identified neuron. Nat Neurosci 9: 17-29.

101. Lorenzetti FD, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Both PKA and PKC are necessary for plasticity in a single-cell analogue of operant conditioning; 2006; Atlanta, Ga. USA. pp. 669.668.

102. Greengard P (2001) The Neurobiology of Slow Synaptic Transmission. Science 294: 1024-1030.

103. Greengard P, Allen PB, Nairn AC (1999) Beyond the Dopamine Receptor: the DARPP-32/Protein Phosphatase-1 Cascade. Neuron 23: 435-447.

104. Svenningson P, Greengard P (2006) A master regulator in the brain. The Scientist 20: 40.

105. Redgrave P, Gurney K (2006) The short-latency dopamine signal: a role in discovering novel actions? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7: 967-975.

106. Menzel R, Leboulle G, Eisenhardt D (2006) Small Brains, Bright Minds. Cell 124: 237-239.

107. Brembs B (2003) Operant conditioning in invertebrates. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 13: 710-717.

108. Axton M (2006) Animal research and the search for understanding. Nature Genetics 38: 497-498.

109. Kleinfeld D, Griesbeck O (2005) From Art to Engineering? The Rise of In Vivo Mammalian Electrophysiology via Genetically Targeted Labeling and Nonlinear Imaging. PLoS Biology 3: e355.

Like this:

Like Loading...

And until today, this paper from last week even flew completely under my radar. I had seen the title and decided it’s not relevant. A collaborator of mine sent it to me after she found it searching for a current affiliation of a former postdoc of hers – which was how she realized how pertinent this work was to our research and sent it to me (which says something about the way scientists are able to stay on top of the literature. Note to self: write separate post!).

And until today, this paper from last week even flew completely under my radar. I had seen the title and decided it’s not relevant. A collaborator of mine sent it to me after she found it searching for a current affiliation of a former postdoc of hers – which was how she realized how pertinent this work was to our research and sent it to me (which says something about the way scientists are able to stay on top of the literature. Note to self: write separate post!).