Due to ongoing discussions on various (social) media, this is a mash-up of several previous posts on the strategy of ‘flipping’ our current >30k subscription journals to an author-financed open access corporate business model.

I consider this article processing charge (APC)-based version of ‘gold’ OA a looming threat that may deteriorate the situation even beyond the abysmal state scholarly publishing is already in right now.

Yes, you read that right: it can get worse than it is today.

What would be worse? Universal gold open access – that is, every publisher charges the authors what they want for making the articles publicly accessible. Take the case of Emerald, a publisher which recently raised their APCs by a whopping 70%. When asked for the reason for their price-hike, they essentially answered “because we can“:

The decision, based on market and competitor analysis, will bring Emerald’s APC pricing in line with the wider market, taking a mid-point position amongst its competitors.

Quite clearly, publishers know their market and know how much they can extract from it (more to that below).

(UPDATE, 13.04.2018: There is data that also Frontiers is starting to milk the cash cow more heavily now, with APC price hikes of up to 40%, year over year)

Already a few years ago. a blog post by Ross Mounce described his reaction to another pricing scheme:

Outrageous press release from Nature Publishing Group today.

They’re explicitly charging more to authors who want CC BY Gold OA, relative to more restrictive licenses such as CC BY-NC-SA. Here’s my quick take on it: https://rossmounce.co.uk/2012/11/07/gold-oa-pricewatch

More money, for absolutely no extra work.

How is that different from what these publishers have been doing all these years and still are doing today? What is so surprising about charging for nothing? That’s been the modus operandi of publishers since the advent of the internet.

Why should NPG not charge, say, US$20k for an OA article in Nature, if they chose to do so? In fact, these journals are on record that they would have to charge around US$50,000 per article in APCs to maintain current profits (more like US$90,000 per article today, see update below).

If people are willing to pay more than 230k ($58,600 a year) for a Yale degree or over 250k ($62,772 a year) just to have “Harvard” on their diplomas, why wouldn’t they be willing to shell out a meager 90k for a paper that might give them tenure? That’s just a drop in the bucket, pocket cash. Just like people will go deep into debt to get a degree from a prestigious university, they will go into debt for a publication in a prestigious journal – it’s exactly the same mechanism.

If libraries have to let themselves get extorted by publishers because of the lack of support of their faculty now, surely scientists will let themselves get extorted by publishers out of fear they won’t be able to put food on the table nor pay the rent without the next grant/position. Without regulation, publishers can charge whatever the market is willing and able to pay. If a Nature paper is required, people will pay what it takes.

Speaking of NPG, they are already testing the waters of how high one could possibly go with APCs. While the average cost of a subscription article is around US$5,000, NPG is currently charging US$5,200 plus tax for their flagship OA journal Nature Communications. So in financial terms at least, any author who publishes in this journal becomes part of the problem, despite the noble intentions of making their work accessible. At this level, gold OA becomes even less sustainable than current big subscription deals.

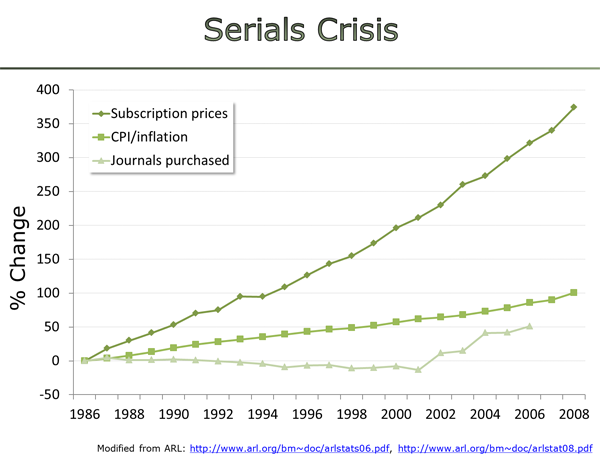

Of course, this is no surprise. After all, maximizing profits is the fiduciary duty of corporate publishers. For this reason, the recent public dreaming about how one could just switch to open access publishing by converting subscription funds to APCs are ill-founded. Proponents may argue that the intent of the switch is to use library funds to cover APC charges for all published articles. This is a situation we have already had before. This is what happens when you allow professional publisher salespeople to negotiate prices with our unarmed and unsupported academic librarians – hyperinflation:

Given this subscription publisher track record (together with the available current evidence of double digit percentage APC increases by NPG, Emerald or Frontiers, or the already now above-inflation increase in APCs more generally), I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating Big Deal APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.

The current scholarly publishing market is worth round US$10bn annually, so this is what publishers will shoot for in total revenue. In fact, if a lesser service (subscriptions) was able to extract US$10bn, shouldn’t a better service (open access) be able to extract 12 or 15bn from the public purse? Hence, any cost-savings assumed to come from corporate gold OA are naive and completely imaginary at this point.

In fact, if the current reluctance to cancel/not renew the more and more obsolete subscriptions is anything to go by, such Open Access Big Deals will be even more of a boon for publishers than subscriptions. The most cited reason for continued subscription negotiations and contracts is perceived faculty demand. One needs to emphasize that this demand here merely constitutes unwillingness to spend a few extra clicks or some wait time to get the article, in most cases. In contrast, when the contracts are about APCs, they do not concern read-access, but write-access. If a library were to not pay a Big APC Deal any more, it would essentially mean that their faculty would be unable to publish. Hence, if librarians now worry about the consequences of their faculty having to click a few extra times to get an article, they ought to be massively worried what happens when their faculty can’t publish in certain venues any more. Faculty response will be disproportionately more vicious, I’d hazard a guess.

One might argue that without library deals, the journals compete for authors, keeping prices down. This argument forgets that we are not free to choose where we publish: only publications in high-ranking journals will secure your job in science. These journals are the most selective of all journals. In the extreme cases, they only publish 8% of all submitted articles. This is an expensive practice as even the rejected articles generate some costs. It is hence not surprising that also among open access journals, APCs correlate with their standing in the rankings and hence their selectivity (Nature Communications being hence just a case in point). In fact, this relationship is the basis for pricing strategies at SpringerNature (the corporation that publishes the Nature brand): “Some of our journals are among the open access journals with the highest impact factor, providing us with the ability to charge higher APCs for these journals than for journals with average impact factors. […] We also aim at increasing APCs by increasing the value we offer to authors through improving the impact factor and reputation of our existing journals.” It is reasonable to assume that authors in the future scenario will do the same they are doing now: compete not for the most non-selective journals (i.e., the cheapest), but for the most selective ones (i.e., the most expensive). Why should that change, only because now everybody is free to read the articles? The new publishing model would even exacerbate this pernicious tendency, rather than mitigate it. After all, it is already (wrongly) perceived that the selective journals publish the best science (they publish the least reliable science). If APCs become predictors of selectivity because selectivity is expensive, nobody will want to publish in a journal without or with low APCs, as this will carry the stigma of not being able to get published in the expensive/selective journals.

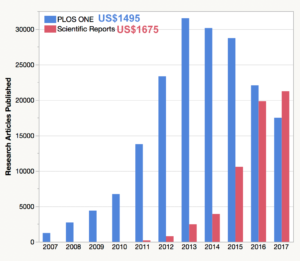

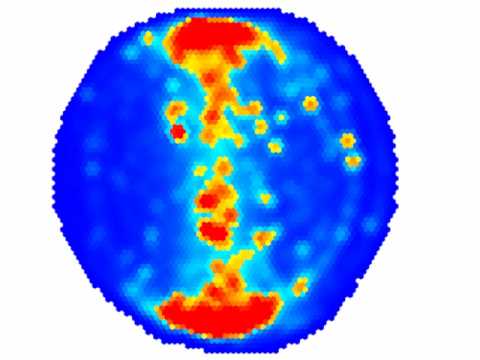

There are even data to suggest that this is already happening. PLoS One and Scientific Reports (another Nature brand journal) are near identical megajournals, which essentially only differ in two things: price and the ‘Nature’ brand. If competition would serve to drive down prices, authors would choose PLoS One and shun Scientific Reports. However, the opposite is the case, falsifying the hypothesis that a gold Open Access market would serve to keep prices in check:

Proponents of the “competition will drive down prices” mantra will have to explain why their proposed method fails to work in this example, but would work if all journals operated in the same way. One could go one step further: just as scholars now are measured by the amount of research funds (grants) they have been able to attract for their research in a competitive funding scheme, it seems only consequential to then also measure them by the amount of funds they were able to spend on their publications in a competitive publications scheme, if the most selective journals are the ones charging the highest APCs: the more money one has spent on publications, the more valuable their research must be. In other words, researchers will actively strive to only publish in the most expensive journals – or face losing their jobs.

Also here, we are already seeing the first evidence of such stratification in terms of who can afford to pay to publish in prestigious journals. A recent study showed that higher ranked (thus, richer and more prestigious) universities tend to pay more for open access articles in higher ranking journals, while authors from lower ranking institutions tend to publisher either in closed access journals or cheaper open venues. Thus, the new hierarchies are already forming, showing us how this brave new APC world will look like.

This, to me as a non-economist, seems to mirror the dynamics of any other market: the Tata is no competition for the Rolls Royce, not even the potential competition by Lamborghini is bringing down the prices of a Ferrari to that of a Tata, nor is Moët et Chandon bringing down the prices of Dom Perignon. On the contrary, in a world where only Rolls Royce and Dom Perignon count, publications in journals on the Tata or even the Moët et Chandon level will only be ignored. Moreover, if libraries keep paying the APCs, the ones who so desperately want the Rolls Royce don’t even have to pay the bill. Doesn’t this mean that any publisher who does not shoot for at least US$5k in their average APCs (better more) fails to fulfill their fiduciary duty in not one but two ways: not only will they lose out on potential profit, due to their low APCs, they will also lose market share and prestige. Thus, in this new scenario, if anything, the incentives for price hikes across the board are even higher than what they are today. Isn’t this scenario a perfect storm for runaway hyperinflation? Do unregulated markets without a luxury segment even exist?

Of course, if libraries refuse to pay above a certain APC level (i.e., price caps), precariously employed authors won’t have any other choice than to cough up the cash themselves – or face the prospect of flipping burgers. Coincidentally, price caps would entail that those institutions which introduce these caps, have to live with the slogan “we won’t pay for your Nature paper!”, so I wonder how many institutions will actually decide to introduce such caps and what this decision might mean for their attractiveness for new faculty.

One might then fall back on the argument that at least journal-equivalent Fiat will compete with Journal of Peugeot for APCs, but that forgets that a physicist cannot publish their work in a biology journal. Then one might argue that mega-journals publish all research, but given the constant consolidation processes in unregulated markets (which is alive and well also in the publishing market as was recently reported), there quickly won’t be many of these around any more. As a consequence, they are, again, free to increase prices. Indeed, NPG’s Scientific Reports has now overtaken PLoS ONE as the largest mega-journal, despite charging more than PLoS ONE, as shown in the figure above. No matter how I try to turn the arguments around, I only see incentives for price hikes that will render the new system just as unsustainable as the current one, only worse: failure to pay leads to a failure to make your discovery public and no #icanhazpdf or Sci-Hub can mitigate that. Again, as in all scenarios and aspects discussed above, also this kind of scenario can only be worse than what we have now.

In the end, it seems the trust in ‘market forces’ and ‘competition’ to solve these problems for us is about as baseless and misguided as the entire neoliberal ideology from which this pernicious faith springs.

At the very least, if there ever should be universal gold OA, the market needs to be heavily regulated with drastic, enforced, world-wide, universal price caps much below current article processing charges, or the situation will be worse than today: today, you have to cozy up with professional editors to get published in ‘luxury segment’ journals. In a universal OA world, you would also have to be rich. This may be better for the public in the short term, as they then would at least be able to access all the research. In the long term, however, if science suffers, so will eventually the public. In today’s world, one needs some tricks to read paywalled articles, such as Sci-Hub or #icanhazpdf or friends at rich institutions. In this brave new universal gold OA world, you need cold, hard cash to even be able to get read. Surely, unpublished discoveries must be considered worse than hard-to-read, but published discoveries?

Thus, from any perspective, gold OA with corporate publishers will be worse than even the dreaded status quo. [UPDATE I: After I wrote this post, the American Research Libraries posted an article pretty much along the same lines, emphasizing the reduced market power of the individual authors above and beyond many of the same concerns I have raised above. Clearly, a quick analysis by anyone will reveal the unintended consequences of merely ‘flipping’ existing journals to an APC-based OA format. UPDATE II: A few month after this post, a recent study by several research-intensive universities in the US also came to the same conclusions as the ARL and yours truly: “the total cost to publish in a fully article processing charge-funded journal market will exceed current library journal budgets”]

Obviously, the alternative to gold OA cannot be a subscription model. What we need is a modern scholarly infrastructure, around which there can be a thriving marketplace of services for these academic crown jewels, but the booty stays in-house. We already have many such service providers and we know that their costs are at most 10% of what the legacy publishers currently charge. How can we afford such a host of modern functionalities and get rid of the pernicious journal rank at the same time?

Institutions with sufficient subscription budgets and the motivation to reform will first have to coordinate with each other to safeguard the back issues. Surprisingly, there are still some quite substantial technical hurdles, but, for instance, a cleverly designed combination of automated, single-click inter-library loan, LOCKSS and Portico by the participating institutions, should be able to cover the overwhelming part of the back archives. For whatever else remains, there still is Sci-Hub et al.

Once the back-issues are made accessible even after subscriptions run out, a smart scheme of staged phasing out of big subscription deals will ensure access to most of these issues for at least 5 years if not more. In this time, some of the freed funds from the subscriptions can be used to pay for single article access for newly published articles. The majority of the funds would of course go towards implementing the functionalities which will benefit researchers to such an extent, that any small access issues seem small and negligible in comparison.

In conclusion, there is no way around massive subscription cuts, both out of financial considerations and to put an end to pernicious journal rank. If cleverly designed, most faculty won’t even notice the cuts, while they simultaneously will reap all the benefits. Hence, there is no reason why people without infrastructure expertise (i.e., faculty generally), should be involved in this reform process at all. Much like we weren’t asked if we wanted email and skype. At some point, we had to pay for phone calls and snail mail, while the university covered our email and skype use. At some point, we’ll have to pay subscriptions, while the university covers all our modern needs around scholarly narrative (text, audio and video), data and code.

It’s clearly not trivial, but the savings of a few billion dollars every year should grease even this process rather well, one would naively tend to think.

UPDATE III (14/12/2017): Corroborating the arguments above, a recent analysis from the UK, a country who has favored gold Open Access for the last five years, comes to the conclusion that “Far from moving to an open access future we seem to be trapped in a worse situation than we started“. I think it is now fair to say that gold open access is highly likely to make everything worse (rather than ‘may‘ as in the title of this post). UPDATE to the update (08/05/2018): A Wellcome Trust analysis also found average APCs to rise between 7% and 11%, i.e., double to triple inflation rate, year over year. Clearly, if more and more gold OA journals indeed would lead to more competition, it’s not driving down prices, on the contrary.

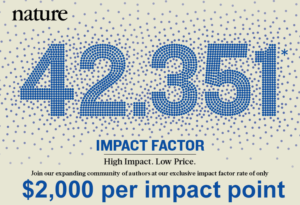

UPDATE IV (19/12/2017): I just went back to Nature‘s old statement in front of the UK parliament, added about 6% in annual price increases (a bit above APC increases and a bit below subscription increases, see above) and arrived at about £22,600-£67,800 that Nature would need to charge for an article in their flagship journal, if they went gold open access today. At current exchange rates, this would amount to about US$30,000-90,000. Rounded out to about US$1000-2000 per impact point:

If one looks at Nature’s actual subscription increases from 2004 to today, they are much lower and amount to an increase of about 25%. This would bring us to pretty much exactly US$50,000 per article, at the current exchange rate. So depending on how one calculates, 30-90k per article for a high impact journal seems what has to be expected.

If one looks at Nature’s actual subscription increases from 2004 to today, they are much lower and amount to an increase of about 25%. This would bring us to pretty much exactly US$50,000 per article, at the current exchange rate. So depending on how one calculates, 30-90k per article for a high impact journal seems what has to be expected.

UPDATE V (14/09/2018): At the persistent request from a reader, I’m extending the discussion on the content of this post to a more suitable forum.

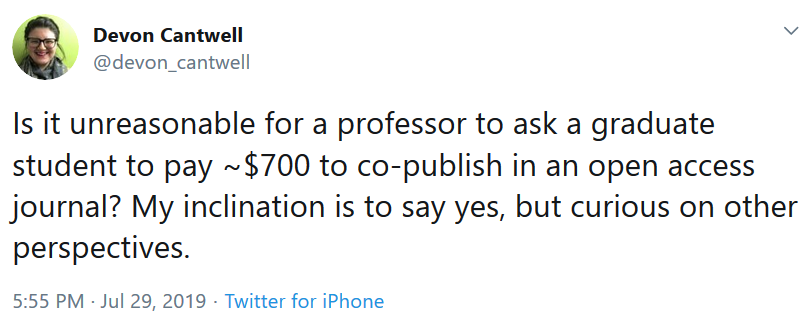

UPDATE VI (30/07/2019): Not surprisingly, students are being asked to co-pay the APCs:

Clearly, those who find tuition fees reasonable will argue that this is the best investment in their career that the PhD student can make. Those who argue that price sensitivity of authors will help bring down publisher prices will also find this very reasonable.

Clearly, those who find tuition fees reasonable will argue that this is the best investment in their career that the PhD student can make. Those who argue that price sensitivity of authors will help bring down publisher prices will also find this very reasonable.

I have two issues with your analysis.

1. Unfair to librarians! You write:

“… libraries let themselves be extorted by publishers out of fear they’ll get yelled at by their faculty, surely scientists will let themselves get extorted by publishers out of fear they won’t be able to put food on the table…”

This implies that librarians face lesser penalties for bucking the system, which is not true. Ask any of the people who kicked you in the shins yesterday on Twitter! It’s the same deal: librarians who take initiative in cancelling subscriptions or breaking off negotiations with publishers face faculty/admin backlash that can cost them their positions. Similarly:

“This is what happens when you allow publishers to negotiate prices with our librarians – hyperinflation”

No, hyperinflation is what you get when you send librarians unarmed and unsupported to negotiate with publishers. If librarians could go in knowing that faculty had their back, we’d see a very different outcome (as, indeed, we have seen those few times when negotiations broke off or Big Deals were canceled).

I know you do not mean to lay blame on libraries without reserving plenty for faculty, but it bears pointing out that the two groups are in this together, are natural allies, and ought to be co-ordinating their attacks.

2. You write:

“Institutions with sufficient subscription budgets and the motivation to reform will first have to coordinate with each other to safeguard the back issues.”

You mean “liberate”, right? (A publisher would say “steal”.) Because unless you make and keep a copy, you lose access when you cancel the last subscription.

In addition to that problem, your model does not cure Glam Fever. While libraries are working behind the scenes to make a seamless, invisible transition from Subscription Access to Sci-Hub, researchers are still publishing in whatever journal they choose, and your own argument is that the stupid fuckers will choose Glam.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments, Bill!

1. I think I can see why someone could read the two sentences you quote the way you read them and this is unfortunate. There is probably a way to say it better and I’ve rephrased both sentences to reflect that effort.

As for the first sentence, I wrote ‘libraries’ not ‘librarians’ because in my experience, subscription cancellations are never done on a whim by one rogue librarian. Of the many subscription cuts I have been witnessing over the years, libraries would first send messages to all faculty asking for information on top of the usage data they have. Then there is an official message from the head of the library detailing why the painful cuts had to be made and what the decision process and reasons were like. The most recent case was cancelling 50% of our university hospital’s library. In every single one of the many cases I have experienced, at least the biological/medical faculty I had direct contact to sighed and threw their arms up in despair over the poor funding of their libraries that they are faced to make such cuts. Obviously, YMMV and things aren’t th same all over the place, but if budget decisions really were a case of loosing your job, what is the problem of informing your boss before you make such an important decision?

Finally, there is a small biological library section at our university run b a single woman. She is in constant contact with us about acquisitions, so she essentially always has faculty backing for anything she decides.

All of this doesn’t mean that a librarian who consistently makes unilateral decisions to the detriment of a particularly influential faculty isn’t at some risk. It of course also doesn’t mean that some trigger-happy decision-maker in some relevant place is only waiting for a mistake to fire an employee. All of these are very real possibilities.

However, neither in the cancellations I have observed, nor at the international librarian meetings I have attended has anyone ever mentioned that whenever librarians negotiate with publishers, thy fear fear for their jobs. I also don’t think that kind of pressure is necessary at all: the social pressure of feeling like all faculty hates you for cutting subscriptions, in particular if you feel that this is your main function, is completely sufficient to put the librarians at such a disadvantage in these negotiations, that even mediocre negotiators can get almost any price they want (in particular if they insinuate that the librarians might lose their jobs if the walk away from that offer).

Of course, my experiences may be completely lopsided and non-representative, so some data on how many librarians have been fired after subscriptions had to be cancelled would be much appreciated to set me straight. I’m of course aware of the regional differences such that, e.g., librarians in Germany are virtually tenured, while their jobs in the US, for instance, are much less secure.

As for the second sentence – I thought that was what I wrote 🙂 Will amend it with your words.

2. If you click on the LOCKSS and Portico links, you’ll see that they’re perfectly legal ways to save the back issues and do not somehow require to ‘liberate’ the back archives. However, there are technical and procedural issues with these services that make it non-trivial to leverage them effectively.

I’m with Bjoern on that, it makes sense economically for the publishers to no longer pretend that they are doing the useful service of dissemination of research. Instead they may jump in the Gold OA business of delivering social validation for researchers, for APCs comparable with the $ for a good university diploma. It’s striking to think that it might be more viable for the publishers to multiply the APC by 6-10, say, than to lower them.

Horror! Rich universities will love it, academic managers will ask for more of it and any ambitious young researcher will fight to be a member of a grant led by a validated researcher, like in a new Prix du Rome.

Dear Björn,

in my eyes you are doing two assumptions in your blog post that are leading to a wrong conclusion.

First you are taking the situation of the top journals (Nature, Science, Cell) which makes less than 1 per mill of the whole scientific output and assume this situation would fit for the whole market of scientific communication. As you describe right this market is to compare with luxury cars, and certainly this is not comparable with the market from average cars.

This leads to the second assumption. You are saying the rest of market of scientific communication is not comparable with average cars because you don’t have the choice to publish in journals from different fields. Certainly is this right but this gives the impression that there is just one journals left in which you have to publish if you are in a specific field. And this is not true else there where no way that Journals like PLOS Biology got established because everybody had the one journal where he has to publish. Beside from the top area of journals there is choice and there is a market. This leads me back to cars. The reason my a specific cars is chosen are quite different because for one it is stilly mainly the brand for others it is the price and for a third persons it is about the features. Now we imagine we are living in gold OA world there will be three journals with nearly the same impact factor in one field: One with a cheap APC and no service at all, a second one with a more expensive APC where the APC included proof reading (or semantic highlighting) and a third a little bit better known one (from one of the big publisher) with the highes APC. If the scientists has at a minimum to pay a share from there research budget there will be makes considerations like in market for average cars.

Still a question is how we can reach this situation. I believe different actions from different players are needed as highlighted in the Recommendations for the Transition to Open Access in Austria (https://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.34079) paper. Only managing the transition for the big publishers can’t be the right answers. Funding of alternative models is also a important part of the Transition to avoid further market concentration.

If there are promising approaches from new players, librarians will be happy to support them. Maybe there will be also new models after a Gold Open Access world but as a basic step to Open Science the transition is needed.

Also there is one point even for Björn one good point in the new Open Access big deals: Libraries are using all the market power they have to establish CC-By as the standard license for paid Open Access.

Disclaimer: I’m librarian and co-author of the Recommendations for the Transition to Open Access in Austria

Excellent comments, thanks a lot Patrick!

To your first point about the %o of the market: You are of course correct, that the few journals that will charge 10-50k per article will not really affect the average price of the entire market (and this is not what I wrote or intended to write).

However, it’s the section of the ‘market’ you need to get a job. From that perspective, as long as you don’t have a job (the vast majority of scientists), the non-GlamMagz might as well not exist, as they are only there to tell your science, which by itself doesn’t mean you’ll have a job. So essentially, we’ll hire those people who are rich enough to be able to afford GlamMagz. That is worse than now, even if the difference isn’t that big for the tax-payer in the short run. In the long run, we we keep hiring those who publish unreliable research from rich institutions/countries, the taxpayer will be worse off than now, as the research they have access to is unreliable. What good is access to unreliable research?

I’m not sure what exactly your second point is trying to convey. On the one hand I read, implicitly, that there won’t be any monopolies/oligopolies in the low-prestige ‘market’. Why would that not happen? There are only a handful mega-breweries left, a handful corporate retailers, a handful academic publishers, a handful car makers, etc. I’m not an economist so I’d like to know why this seemingly ubiquitous consolidation should not happen in this low-prestige segment? On the other hand, I see the idea that each journal would be offering different services, different formats, functionalities, etc. to justify different prices? I’m not sure, but that would definitely qualify as worse than today: our literature would be even more balkanized than it is now, with some journals being even more obscure than today, researchers from poor countries only being able to publish in the least visible, most functionality-stripped journals. That would be a complete nightmare! I’d take subscriptions with Sci-Hub any day over that scenario, even if publishers doubled the prices!

So I cannot see anything positive ion the scenarios as I understand them, on the contrary, none of these would make things any better and some of them even worse than what I imagined.

However, let’s say we have a market that drives down prices and there are standards that the 30k journals would really all get together and agree to common standards that would eliminate balkanization and lead to a homogeneous scholarly literature that one actually technically can use, e.g., content-mining on, with standards that allow the integration of text, audio, video, data and code. I have never heard of a market where competitors would actually do that, but let’s just assume that hypothetical scenario for the sake of argument. All that would still not eliminate journal rank which is a major player in the unreliability of our research and contributes to hiring scientists who do unreliable work. In this case, the taxpayer would pay less money to access increasingly unreliable research. Personally, I don’t find this to be a desirable trade-off: “ok, dear taxpayer, you wanted access, here you have it, but now what you read isn’t worth what you paid for”. That’s not what I would consider a message that is going to sell very well.

I’m actually a great fan of the Austrian declaration as it doesn’t mention publishers specifically, but very vaguely talks about “entities”: with today’s technology, I cannot see any rational reason why one needs someone else to physically take our works from us. In a scholarly infrastructure run by our institutions, we can have a flourishing market around services. Just as universities chose which company should do their plumbing, or they do it themselves, which company should handle HVAC, or to do it in-house, universities should chose how much of the services around text, data and code they want to do themselves and how much they want to pay which companies for. Giving away our most valuable assets (narrative, data and code) just makes us liable to extortion as we have been witnessing for a couple of decades now. Why repeat the same mistake? Shouldn’t we learn from history?

Well, on one hand I agree, that we don’t want commercial publishers to rule monopoly-like all the scientific journals. We cannot afford to pay them even more money. We want to have open access to increase the impact of science and to serve the scientific progress best.

On the other hand I have some questions and comments:

1) You are describing the current flipping strategy as:

> strategy of ‘flipping’ our current >30k subscription journals to an author-financed open access corporate business model

Where did you come up with that? This is different compared to the https://oa2020.org/mission/ :

“We aim to transform a majority of today’s scholarly journals from subscription to OA publishing in accordance with community-specific publication preferences. At the same time, we continue to support new and improved forms of OA publishing.”

Moreover, you don’t mention open access offsetting contracts, which IMO are a key feature of the current transition strategy. Why the omission?

2) Impact factor and journal-based rankings of articles/scholars are ridiculous

> only publications in high-ranking journals will secure your job in science

Even if this is the status quo, we shouldn’t stop here. Who can best evaluate the work of scientist? Other scientists! Therefore scholars should say clearly that it is ridiculous to use these journal rankings and change the evaluation processes. You agree on that

> put an end to pernicious journal rank

Yes, but no one will do that for you, the scientists themselves have to take actions to stop this practice. It may take a long time, but even in the meantime we shouldn’t use journal ranking in argumentation.

3) Journals are not comparable to cars

Cars can be fast, secure, or just looking good. Based on what is important for me, I can be willing to spend more money on a car with some special features. However, the same is IMO not clear for journals, where journals are just the compound around the articles. The title page or layout of the journal is not important, quality depends on the peer-review process which are other scientists doing and therefore not part of the journal, IF are ridiculous. As a reader I will read the articles, which are normally just PDFs and they are looking quite similar among the journals of a given discipline.

Actually, I think there might still be some more services which publishers are already or maybe could in the future provide. In my future vision the journal editors can (based on such options) choose between different publishers and maybe even mix different services from different publishers (commercial ones, not-for-profit, local infrastructure institution, scientific associations).

Thanks a lot, I don’t have much to say to your comments, I think I agree with most if not all of them. Please let me try to address your questions:

1. Mainly from this paper:

https://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:2148961:7/component/escidoc:2149096/MPDL_OA-Transition_White_Paper.pdf

and the discussions and developments since it was published, especially with regard to some policy decisions in the UK before this paper and in the Netherlands afterwards. Luckily, as I see it, these are scenarios and ideas being bandied about and discussed. As far as I can tell, none of these plans have been set in motion, as of yet, but they seem to be gaining traction, in particular as organizations with money and influence (e.g., Max Planck) are behind some of the initiative and have a stake in the discussion as Max Planck is now a publisher as well with a significant amount of tax-funds sunk into eLife.

From the abstract:

“This paper makes the strong, fact-based case for a large-scale transformation of the current corpus of scientific subscription journals to an open access business model.”

That’s what a lot of people are talking about right now (although it is by no means the only, hopefully not even the dominant approach).

About offsetting contracts: a far as I understand those, they’re there to make sure hybrid journals aren’t double-dipping? If this is what you refer to then they’re outside the scope of this post: I only wanted to think about what would happen if we had a universal gold OA situation, no matter how we would get there.

2. Your write: “Yes, but no one will do that for you, the scientists themselves have to take actions to stop this practice. It may take a long time, but even in the meantime we shouldn’t use journal ranking in argumentation.”

You are very correct – in principle. Our paper:

https://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00291/full

was written with the intention to provide probably the strongest argument for scientists: evidence. One can plead ethics all one wants, pleading rarely changes people’s behavior (maybe their minds, but not their behavior). Evidence that the current system rewards the least reliable scientists should be the strongest argument to let go of journal rank.

However, most prominent decision-makers in German science have publicly stated that they don’t care about such evidence:

https://bjoern.brembs.net/2015/07/evidence-resistant-science-leaders/

If even the strongest argument fails, there is no reason to sit back and grow old while one is waiting for some miracle to occur that makes journal rank magically disappear (in particular as scientists have been pleading to drop journal rank for about the last 20 years with no effect at all). 20 years of pleading hasn’t worked, evidence isn’t working – what is left that we should wait for? Superman? 🙂

3. You are very correct, journals are not comparable to cars, but proponents of gold OA ‘markets’ invoke the impression that they are, that authors can then shop around for the journal that suits them best. Of course this is quite unrealistic for the reasons laid out in the post and in my reply to Patrick. The one scenario hinted at by Patrick, where every journal is different from every other journal by format, services, visibility, prestige, functionalities and price, would make journals more similar to cars – but I personally would find this situation much worse than even the horror-scenario I developed in the post.

Dear Björn,

a bit of healthy paranoia cannot hurt! (I share that one with you). But on the other hand:

– Sci-Hub will no longer be a fall-back solution, since Elsevier is about to or has bought it already ;-)) Similarly, I believe that Portico etc. don’t have rights to make back issues available to non-subcribers of such journals. We will have to find other solutions for the past, I am afraid.

– As to the future: Whether it is the impact factor or the mere fact that a journal has been blessed by Thomson Reuters (i.e.: included in their master list) or some other indicator: Founding a new journal – which university/community operated journals would be – and getting authors to write for them is very much an uphill battle, if there already is an established, influential journal.

Wut? Paranoia? Are you saying there’s someone after me? 🙂

I completely agree that setting something new up is very difficult if the old system still exists. There are some ‘flipped’ journals that have managed this well, but those instances where the old journal just died were considerably more successful.

Welcome to Fool’s Gold! https://j.mp/foolsGOLDoa

You nailed it, Stevan!

Could we, once and for all, agree not to confuse Gold OA with APC-Gold OA or, as Stevan puts it, as Fool’s-Gold. Publishers have been very good at feeding this confusion, but there is no reason why OA supporters should assist. There is APC-Gold and there is non-APC-Gold. let us keep this distinction clear.

I hope I’ve done that from the very outset in this post by qualifying ‘gold OA’ in the first and many other mentions with ‘corporate business model’ or ‘author financed’ and similar?

I was not aiming at you specifically, but I think that either Stevan’s “fool’s Gold” or my own APC-Gold are far more accurate. There are problems with the APC model even when practised by “good guys” (e.g. PLoS). And we need some quick, clear, unambiguous way to characterize non-APC-Gold from APC-Gold. I just did! Each approach is absolutely distinct from the other, even though there are many gradations in APC-Gold and many variations in the business models of non-APC-Gold. APC-Gold opens the possibility of Hybrid journals, and that of so-called “predatory” journals. Non-APC-Gold does not.

I thought “Platinum OA” was used for that (but I’m aware people also have used ‘diamond’ and that none of the two really have caught on). Hence, I stick with common usage and use qualifiers, but I agree that the APC model hurts OA’s perception.

Hi Bjorn. I hope you can put a version of this comment at the right place(s) in the draft journal-flipping report now open for public comment.

https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/programs/journal-flipping/public-consultation/

The draft report (by Dave Solomon, Bo-Christer Björk, and Mikaell Laasko) covers the full range of conversion methods actually tried and proposed. My interest is getting people like you –through their comments– to recommend scenarios they find worth recommending and advise against scenarios they find unwise or harmful.

The public comment period won’t last much longer. FYI, here are some more details on the public comment period.

https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/programs/journal-flipping/call-for-public-comments/

So many thanks for alerting me to this opportunity. For lack of time I have just left the link there, but I can, of course, also leave a longer comment at a later time.

Dear Björn,

Thanks for your post — it raises points worth discussing. However, I find it rather biased in not acknowledging that several different approaches to Gold OA (even to APC-based Gold OA) are co-existing at the moment, most of them being capped APC funds provided by Continental European research funders. The text also fails to mention the extensive work being undertaken by the library community in ensuring transparency to the APC fees being paid, in a way that will make it easy to identify and (hopefully) shame artificial fee increases. There’s a frequent argument against funding caps, namely that APC fees will raise to match them: this is not happening in any of the capped funding initiatives presently going on. As for the benefits of the generic Gold OA model that the post does not mention either, there is the extraordinary level of political support shown earlier this week at the Open Science conference held by the Dutch EU Presidency, which is already being channeled into looking at the research assessment procedures as one of the key roots of the bigger issue. There is the outstanding opportunity for library involvement and collaboration around data collection & sharing. And there is the fact that by bringing libraries much closer to researchers, it opens the way to a better, more effective advocacy around where it’s sensible to publish. All of this is part of a wider approach which includes journal flipping and Green OA. The MPDL paper and the offsetting agreements are just a way forward and it’s unfair and misleading to judge Gold OA solely through its lense.

Thanks a lot for your perspective! My post is just a cautionary note against a path that I currently see a few major players getting dangerously close to and some powerful publishers actively pursuing. Of course, I have left those out that do not seem to be that close to this path. Had I included all those initiatives, this post would likely have turned into a book 🙂

I would be more than happy, if your assessment were correct, that all players are aware of the possible dangers and that the chances of us ending up there are minute. In other words, if my lense were myopic and my fears unfounded, that’d be good for all of us. However, some of the reactions here and elsewhere suggest to me that at least I’m neither unfair nor misleading.

As other comments noted, there are many kinds of Gold OA, so I take this as an argument against “Gold OA at any cost” rather than against Gold OA per se, right? In particular, it can be unwise to force people to publish in Gold OA.

In my opinion this post underestimates the importance of free culture, i.e. of free copyright licenses and copyleft. Gold OA is really golden only if it’s free, i.e. CC-BY or CC-BY-SA (or CC-0), because then all content can be republished and “forked” freely by anyone without copyright worries. So, as an institution, I’d make a policy forcing people to adopt a certain copyright licensing, rather than on the publishing method.

Which brings me to my two questions on the proposed single-click ILL + LOCKSS/Portico, which is a no-brainer, but surprisingly hard to implement institutionally (and in practice Sci-Hub is already doing it).

1) How would you get institutions on-board in countries where digital ILL is legally risky (see e.g. Communia’s answer 32b to the 2014 EU consultation on copyright, «The interlibrary loan between universities and national libraries is not a reality» https://www.communia-association.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/140305communia_response_simple.pdf )?

2) Do you envisage self-archiving repositories and other institutionally-run journals or databases to be part of such automatic ILL? I think that would be easier to achieve, as each institution clearly has an interest in circulating their researchers’ publications, but not in circulating the publications they happen to be subscribed to (they may even fear free-riders for future subscriptions, or the loss of a competitive advantage).

Finally, I agree with the other comments that the cases you consider are on the extreme side. In many universities of Italy, I see university-run OA OJS instances going very well, especially for humanities. Such systems replace outdated methods, increase transparency on the costs of research and produce a natural incentive to take control of journals by running them in-house (with internal staff or, why not, an external consultancy from the same publishers which previously owned them).

Thanks for your thoughts! You write:

"As other comments noted, there are many kinds of Gold OA, so I take this as an argument against “Gold OA at any cost” rather than against Gold OA per se, right?"

Yes – if by 'cost' you mean anything that's going to be worse than now 🙂 Gold essentially means "open upon publication". If our repositories became the place where we publish, it would be gold 🙂

If I had my way, the default on our infrastructure would always be open, with very liberal re-use rights. Only if there are good reasons, people will have to go the extra mile to make their work less open. In other words, the opposite of today.

1) As you point out, not only the technicalities but also the legal framework for securing the back-archives leaves much to be desired. This is where I think most current efforts ought to be directed. After all, there is little that is of more value in this context than our content. I'm no legal scholar, so I would argue to use ILL to the outmost extent legal and then use safety in numbers (institutions already have to coordinate for technical and financial reasons) to challenge the laws in court. Of course, the more ubiquitous LOCKSS and portico were, the less need for ILL there were, although it would never get eliminated as we have it today as well.

I'd also argue that CLOCKSS will start to come into play as more and more subscriptions are cut and publishers eventually go belly up.

Be that as it may, you are correct that there are significant hurdles to be overcome – and some of them are being addressed on the legislative end, see e.g., the initiative for a research exception for copyright:

https://libereurope.eu/liber-position-statement-copyright-in-the-digital-age/

2) Absolutely! ILL would try to fetch the most easily obtainable copy. One way would be to get the repository version, another would be an automated email to the author with single-click approval. I'm sure imaginative librarians can come up with at least a dozen or more different ways of digitally localizing a document 🙂

We also run four free/free OA journals here at our university, so you are right that it is likely not the institutions themselves who are very keen on corporate OA! Least of all, I'd assume, libraries who would see themselves squeezed between faculty and publishers yet again. No, you are right, the drivers in this game are mostly other players.

thanks Björn for your considerations;

i suggest you to consider what happens in High Energy Physics,where SCOAP3 project https://scoap3.org/ funds APC-Gold OA model you oppose. However, why this model could not extend to other fields of Academic Publishing?

Thank you for your valuable comment, Giovanni.

I was very happy, a few years ago, when I heard about the SCOAP3 project. Today, I still think it’s a good and worthwhile initiative, but I think it has shown why it can only be a transition project. For one, the prices are still inflated and participating institutions complain about the complexity and bureaucracy of the pricing calculations. Moreover, the effectiveness of the approach may be questioned, as only 50% of all high-energy physics papers are now formally accessible, even 4 years after they started. Finally, the outdated model of journals is still propped up, something which I would consider worse than having no access: journals make our research balkanized, unreliable and unsuitable for modern approaches such as content-mining. Access alone only provides a temporary fix to some of our problems. Access is not bad in itself, of course, but if we focus exclusively on just access, we will lose sight of the bigger problems will will be left unsolved.

Dear Björn, thank for your reply; if matter of discussion regards the Journals role on schorarly dissemination, i am not so skilled to discuss with you; i am mostly involved in HHS fields where we have a Monograph/series model so that talking about content or data mining is really hard for me to imagine!

If possible, i would offer my 2 cents points of view about Gold OA with APC model, in which i believe!

The big new (if it is so new) is that Gold OA it is becoming really matter of interest of Academic Publishers and University Presses (and not only their Libraries!) to get a substainable economic model for Scientific dissemination of research. This is true both for big Fish than for smaller ones, so that competition could re/start using new rules and involving services offered to authors.