These days, many academic publishers can be considered mere Pinos: ‘Publishers in name only’. Instead of making scholarly work, commonly paid for by the public, public, as the moniker ‘publisher’ would imply, in about 80% of the cases, they put them behind a paywall. As if that weren’t infuriating enough, profits and paywall costs add up such that the final cost to the taxpayer is tenfold higher than if each article were just made, you know, public.

The only reason scholarship is in this embarrassing calamity is historical baggage. Nobody in their right mind would construct scholarly communication in the current way if they had to design it from scratch.

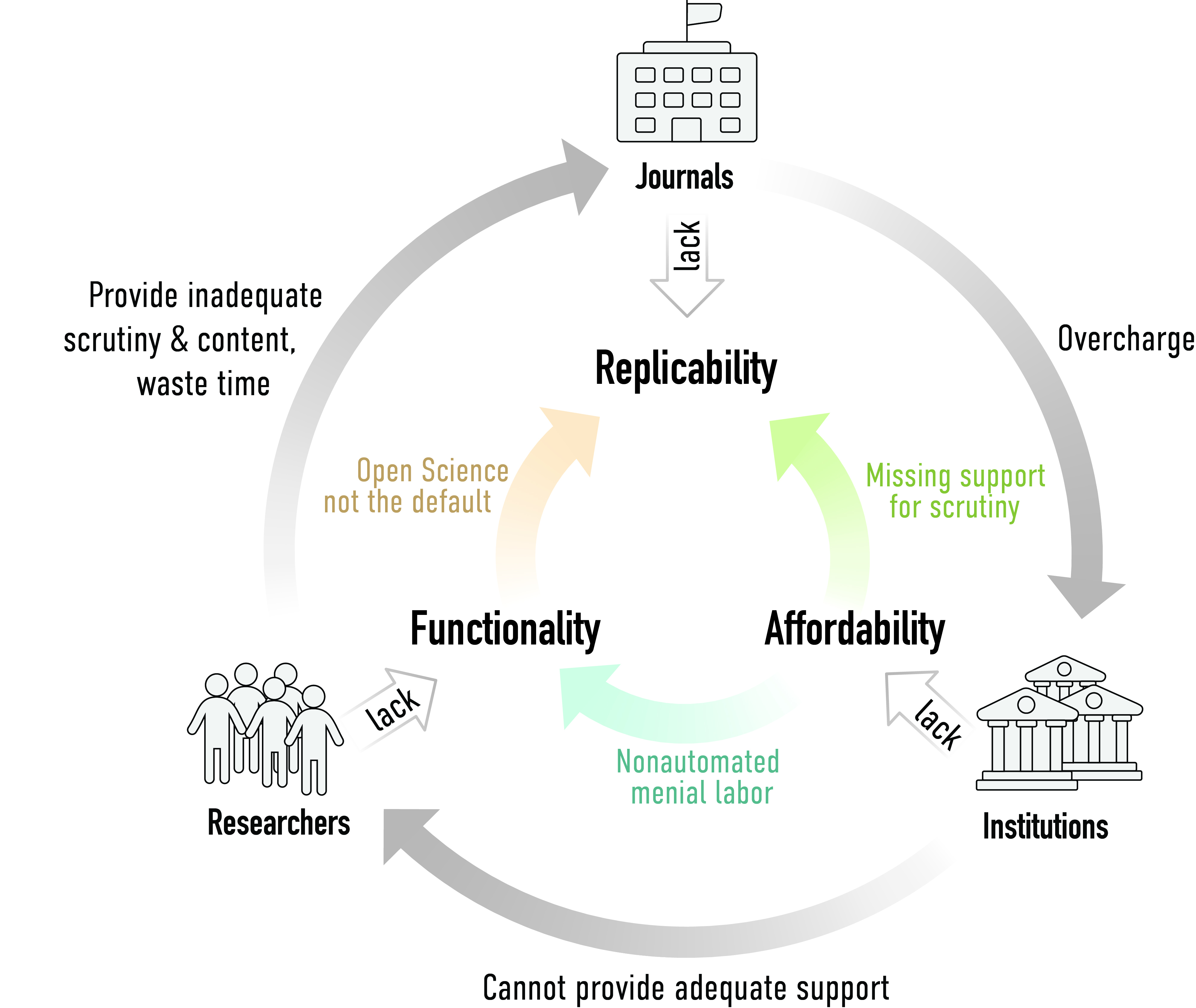

So how would one design our scholarly communication infrastructure from scratch, without historical baggage? To do that, one would have to start by defining the basic functionalities of this infrastructure. Importantly, the infrastructure would have to cover all of scholarships output: our narratives (text, audio, video) as well as our data and code. Current technology should save scholars time and effort when reading, writing, citing as well as assist data collection and analysis both from the data and from the code end. Given that what most of our institutions are offering us today still remains at the technical level of early 1990s technology, the move to current technology should cover most of these desired functionalities.

While modern information technology may be cheap and getting cheaper every day, it isn’t free. The money has to come from somewhere. At what scale could this infrastructure be estimated to come to lie? The UN estimates scholarship at around 7 million full time equivalents, so that is the ballpark figure of users to be served, probably a few million more for the part-time scientists. Researchgate claims to have about 11 million users, so that fits within this ballpark. Compared to the billions of Facebook users, the hundreds of millions of Instagram or Twitter users, this is technical peanuts. A service that serves this size of user base is not facing any major technical issues. Instagram cost Facebook US$1 billion, Researchgate runs on about 50 million, Twitter is estimated to be worth about US$15 billion. Given the size of the scholarly user base, a scholarly infrastructure would probably cost somewhere towards the lower end of this scale to acquire and much less to run. Much of the scholarly functionalities that would be missing in an off-the-shelf social platform already exist either as open source solutions or in various initiatives, start-ups or also as conventional software solutions. Hence, it is probably safe to say that about 1-3 billion US$ would buy us a rather luxurious solution to all our problems off the shelves of currently available technological merchandise.

The running costs for our current journal-based ‘publication’ system are about US$10 billion annually. We know from various sources that actual costs of making these works public are around or less than US$1 billion per year. Thus, if some unfortunate event would force us to redesign scholarly communication from scratch, we’d only need 10% of our current spending to keep the basic article publications running, the way we do now (just with every article being truly public). Conversely, we’d have US$9 billion annually for innovations, data and code, if we keep infrastructure spending at current levels.

Of course, crucial for any such system is governance. Geoffrey Bilder, Jennifer Lin and Cameron Neylon have provided an excellent outline for governing the scholarly commons. Besides governance, a second prerequisite for the scholarly commons is a organizational framework that keeps costs low but provides space for innovation. The last century has provided some rather convincing evidence that well-designed markets can provide precisely such a framework.

Historically, we have not enjoyed such a market. Pino profit margins exceeding 40% are only realizable precisely because there is no competition: almost every article exists only once with any given Pino (at least the legal copies). Hence, each Pino had the de facto monopoly for that article and could charge whatever its customers were able to pay.

However, if the scholarly work instead remained in the hands of scholars, within the scholarly commons, then companies could compete with each other for the best services, the most convenient and innovative functionalities around this scholarship. Institutions would be able to leverage tried and tested bidding procedures to stimulate competition and have a choice of competitors. Alternatively, institutions could decide to invest (part of) their infrastructure funds into in-house expertise and put pressure on companies to provide better value for money than the in-house services. In other words, such a framework for the scholarly commons would afford institutions the same kind of leverage and range of choices and strategies as they enjoy for any other infrastructure, be it IT hard/software, HVAC, electricity, water, etc.

For the past few years, several initiatives and organizations have started to implement such a framework. For instance, the Wellcome trust has launched Wellcome Open Research, a platform for publishing Wellcome funded researchers. Currently, F1000Research runs the technology behind this platform, but that may change in the future, if better competitors come along – without any user necessarily having to notice anything changing. Scholarly societies which run their own journals are starting bidding processes for the service providers to run their journals. The Open Library of Humanities is running their journals on fixed-term contracts with clauses that allow the journals to switch providers if OLH is not satisfied. All of these examples show that this type of framework is both currently in use and viable. Wherever costs are known, they come to lie around the 10% figure given above, i.e., the organizations running these journals or platforms are saving about 90%, compared to legacy Pino solutions. However, most current journals are owned by publishers, preventing any switch in service providers.

If current Pinos really cared as much about scholarship as they keep emphasizing, they would get on board with these more recent developments, maybe help develop the scholarly standards needed for a scholarly commons, and offer their services around these standards. Interestingly, eLife (not a Pino) recently announced a collaboration to start developing the core of such open standards. Pinos, on the other hand, indicate through their acquisitions, lobbying, visions and policies their ongoing efforts to cement current profit margins and to prevent or stall the transition from profiteering to servicing.

“Pino” has echoes of “Dino” and “puny” to me. Let’s make them extinct.

Comments are closed.