There can be little doubt that the defunding of public academic institutions is a main staple of populist movements today. Whether it is Trump’s budget director directly asking if one really needs publicly funded science at all, or the planned defunding of the endowments of arts and humanities or the initiatives to completely abolish the EPA and other science agencies. Also across the pond, there are plenty of populist parties and other Trump fans who certainly also strive to mimic their idol and rid their countries of intellectuals who may see through their shenanigans, or use evidence to oppose their policies.

For decades, these anti-intellectual forces have been fighting science tooth and nail around the globe. Recently, in the UK, a website, whose former boss is now the main advisor to Trump in the White House, titled: “When you hear a scientist talk about ‘peer-review’, you should reach for your Browning” (link to archive.org snapshot). The author argues that the scholarly literature we refer to when making scientific claims was written by “charlatans and chancers”.

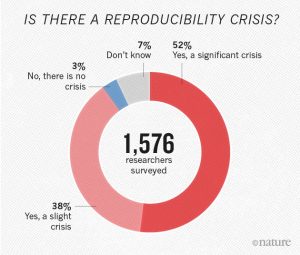

The horrifying aspect of this article is that from their perspective, this isn’t even ‘fake news’. Already in 2005, John Ioannidis found that “most published research findings are false“. Since then, numerous reports have been published which seem to suggest that our scholarly literature is much less reliable than one would desire. While the scope of irreproducibility is not yet clear, the overwhelming majority of scientists believes the problems are bad enough to justify the term ‘replication crisis’:

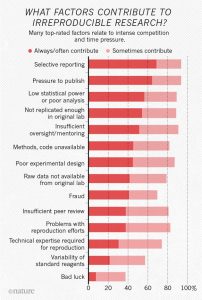

Besides criminal intent and inadequate training, one major factor in the potential unreliability of our scholarly literature is socioeconomic in nature. The two factors deemed to contribute most to irreproducible research were selective reporting and the pressure to publish:

In an attempt to provide accountability and to combat biases in scholarship, we have introduced quantitative measures to assess individual scholars. Most widely used in hiring, promoting and funding scholars are two general aspects: quality and productivity of scholars. To quantify quality, individuals are commonly assessed by where they publish, for productivity, how much they publish. Both of these quantifications have been shown to be highly problematic, especially in today’s hyper-competitive scholarly environment.

In the fields where scholars publish their experiments in journals, it has been shown that the most prestigious journals publish the least reliable science. So by preferentially hiring, promoting and funding scientists who publish in these journals, we are also rewarding unreliability, to some extent. Similarly, if we count the number of journal articles with novel findings, we are selecting for underpowered studies with erroneous conclusions.

Taken together, these data suggest that even if the reliability of our current literature turns out to be higher than the initial reports suggest, we are currently running a system poised to make it less reliable every year. Consequently, inasmuch as anti-science forces seize on the unreliability of the scholarly literature to support their defunding plans, the horrifying possibility emerges, that every stakeholder – academic, librarian or publisher – who, willingly or not, props up the current journal system, may be inadvertently supporting anti-intellectual agendas.