Even without retractions, ‘top’ journals publish the least reliable science

In: science politicstl;dr: Data from thousands of non-retracted articles indicate that experiments published in higher-ranking journals are less reliable than those reported in ‘lesser’ journals.

Vox health reporter Julia Belluz has recently covered the reliability of peer-review. In her follow-up piece, she asked “Do prestigious science journals attract bad science?“. However, she only covered the data on retractions, not the much less confounded data on the remaining, non-retracted literature. It is indeed interesting how everyone seems to be attracted to the retraction data like a moth to the flame. Perhaps it’s because retractions constitute a form of ‘capital punishment’, they seem to reek of misconduct or outright fraud, which is probably why everybody becomes so attracted – and not just journalists, scientists as well, I must say. In an email, she explained that for a lay audience, retractions are of course much easier to grasp than complicated, often statistical concepts and data.

However, retractions suffer from two major flaws which make them rather useless as evidence base for any policy:

I. They only concern about .05% of the literature (perhaps an infinitesimal fraction more for the ‘top’ journals 🙂

II. This already unrepresentative, small sample is further confounded by error-detection variables that are hard to trace.

Personally, I tentatively interpret what scant data we have on retractions as suggestive that increased scrutiny may only play a minor role in a combination of several factors leading to more retractions in higher ranking journals, but I may be wrong. Indeed, we emphasize in several places in our article on precisely this topic that retractions are rare and hence one shouldn’t place so much emphasis on them, e.g.:

“These data, however, cover only the small fraction of publications that have been retracted. More important is the large body of the literature that is not retracted and thus actively being used by the scientific community.”

Given the attraction of such highly confounded data, perhaps we should not have mentioned retraction data at all. Hindsight being 20/20 and all that…

Anyway, because of these considerations, the majority of our article is actually about the data concerning the non-retracted literature (i.e., the other 99.95%). In contrast to retractions, these data do not suffer from any of the above two limitations: we have millions and millions of papers to analyze and since all of them are still public, there is no systemic problem of error-detection confounds.

For instance, we review articles that suggest that (links to articles in our paper):

1. Criteria for evidence-based medicine are no more likely to be met in higher vs. lower ranking journals:

Obremskey et al., 2005; Lau and Samman, 2007; Bain and Myles, 2005; Tressoldi et al., 2013

2. There is no correlation between statistical power and journal rank in neuroscience studies:

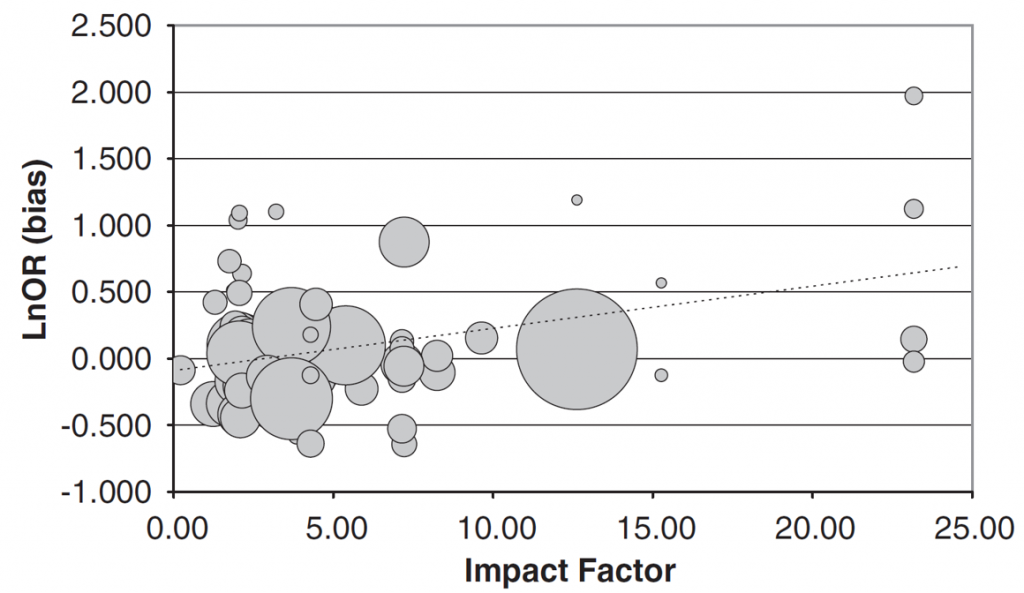

Figure 2:

3. Higher ranking journals tend to publish overestimates of true effect sizes from experiments where the sample sizes are too low in gene-association studies:

Figure 1C:

4. Three studies analyzing replicability in biomedical research and found it to be extremely low, not even top journals stand out:

Scott et al., 2008; Prinz et al., 2011; Begley and Ellis, 2012

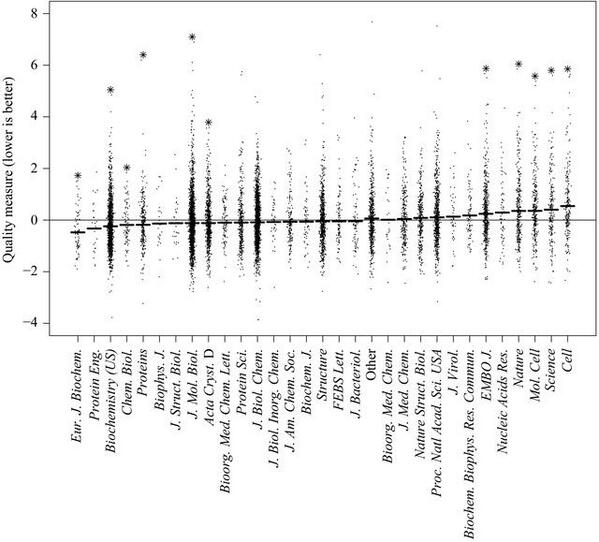

5. Where quality can actually be quantified, such as in computer models of crystallography work, ‘top’ journals come out significantly worse than other journals:

esp. Fig. 3 in Brown and Ramaswamy, 2007

After our review was published, a study came out which showed that

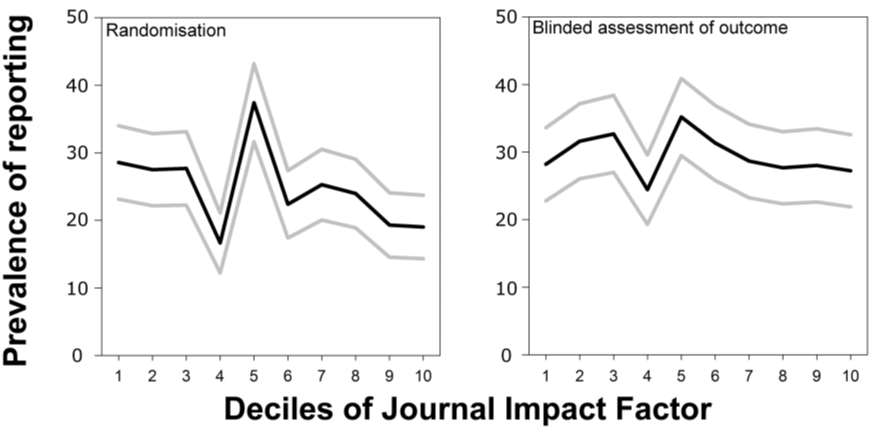

6. In vivo animal experimentation studies are less randomized in higher ranking journals and the outcomes are not scored more often in blind in higher-ranking journals either:

Hence, in these six (nine including the update below) areas, unconfounded data covering orders of magnitude more material than the confounded retraction data reveal only two out of three possible general outcomes:

a) Non-retracted experiments reported in high-ranking journals are no more methodologically sound than those published in other journals.

b) Non-retracted experiments reported in high-ranking journals are less methodologically sound than those published in other journals

Not a single study we know of (there may be some we missed! Let me know.) shows the third option of higher-ranking journals publishing the most sound experiments. It is this third option that at least one analysis should have found somewhere if there was anything to journal rank with regard to reliability.

Hence, even if you completely ignore the highly scattered and confounded retraction data, experiments published in higher ranking journals are still less reliable than those published in lower ranking journals – and error-detection or scrutiny has nothing to do with it.

In that view, one may interpret the observation of more retractions in higher ranking journals as merely a logical consequence of the worse methodology there, nothing more. This effect may then, in turn, be somewhat exaggerated because of higher scrutiny, but we don’t have any data on that.

All of this data is peer-reviewed and several expert peers attested that none of the data in our review is in dispute. It will be interesting to see if Ms. Belluz will remain interested enough to try and condense such much more sophisticated evidence into a form for a lay audience. 🙂

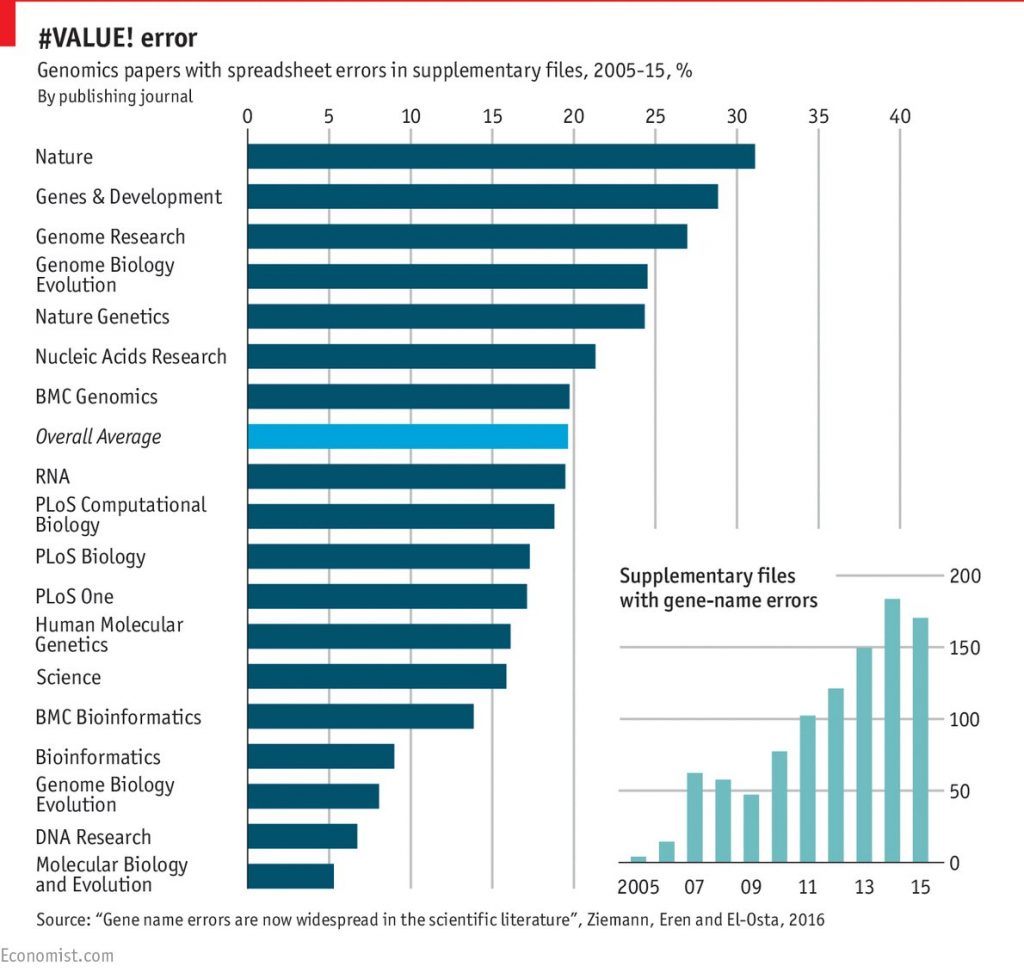

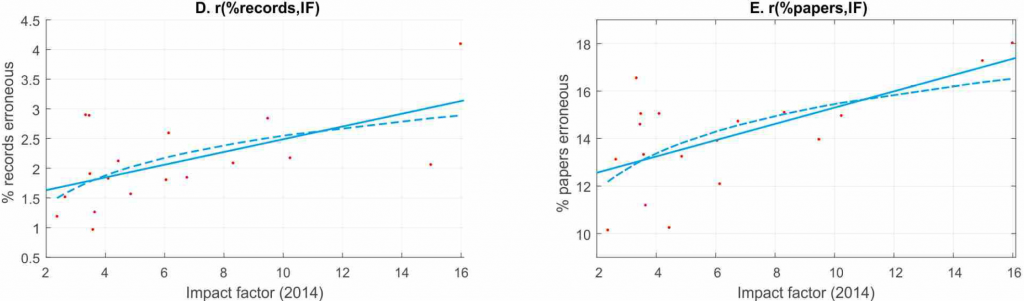

UPDATE (9/9/2016): Since the publication of this post, two additional studies have appeared that further corroborate the impression that the highest ranking journals publish the least reliable science: In the field of genetics, it appears that errors in gene names (and accession numbers) introduced by the usage of Excel spreadsheets are more common in higher ranking journals:

The authors speculate that the correlation they found is due to higher ranking journals publishing larger gene collections. This explanation, if correct, would suggest that, on average, error detection in such journals is at least not superior to that in other journals.

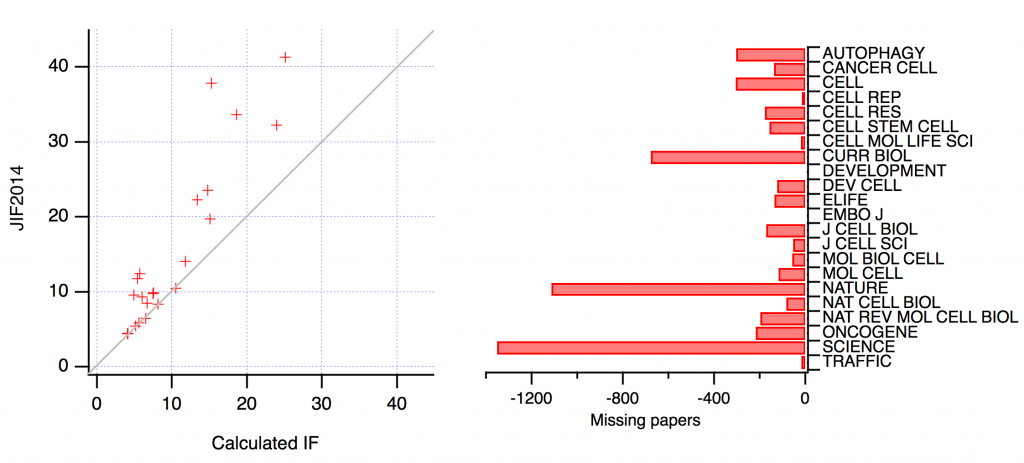

The second study is on the statistical power of cognitive neuroscience and psychology experiments. The authors report that statistical power has been declining since the 1960s and that statistical power is negatively correlated with journal rank (i.e., a reproduction of the work above, with an even worse outcome). Moreover, the fraction of errors in calculating p-values is positively correlated with journal rank, both in terms of records and articles (even though I have to point out that the y-axis does not start from zero!):

Thus, there are at least three additional measures in these articles that provide additional evidence supporting the interpretation that the highest ranking journals publish the least reliable science.

Thus, there are at least three additional measures in these articles that provide additional evidence supporting the interpretation that the highest ranking journals publish the least reliable science.

UPDATE II (9/5/2017): Since the last update, there has been at least one additional study comparing the work in journals with different impact factors. In the latest work, the authors compared the p-values in two different psychology journals for signs of p-hacking and other questionable research practices. Dovetailing the data available so far, the authors find that the journal with the higher impact factor (5.0) contained more such indicators, i.e., showed more signs for questionable research practices than the journal with a lower impact factor (0.8). Apparently, every new study reveals yet another filed and yet another metric in which high-ranking journals fail to provide any evidence for their high rank.

UPDATE III (07/03/2018): An edited and peer-reviewed version of this post is now available as a scholarly journal article.