The DFG is a very progressive and modern funding agency. More than two years ago, the main German science funding agency signed the “Declaration on Research Assessment” DORA. The first point of this declaration reads “Do not use journal-based metrics […] as a surrogate measure of the quality of individual research articles, to assess an individual scientist’s contributions, or in hiring, promotion, or funding decisions.” Last year, the DFG joined the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment” CoARA and sits on their Board. The CoARA principles also emphasize: “Abandon inappropriate uses in research assessment of journal- and publication-based metrics”. In their position paper from last year, the DFG states in two places in the executive summary:

the assessment of research based on bibliometrics can provide problematic incentives

and

A narrow focus in the system of attributing academic reputation – for example based on bibliometric indicators – not only has a detrimental effect on publication behaviour, it also fails to do justice to scholarship in all its diversity.

In a world in which impact factors and other bibliometric measures still reign supreme, these are laudable policies that set the DFG apart from other institutions. In fact, these steps are part and parcel of an organization with a long tradition of leveraging its power for good scholarly practices. Even before DORA/CoARA the DFG has continually evolved their policies to minimize the effect of publication venue on the assessment of applicants.

Given this long and consistent track-record, now complemented by two major official statements, one could be forgiven to think that applicants for funding at the DFG now feel assured that they will not be judged by their publication venues any longer. After all, journal prestige is correlated with experimental unreliability, so using it as an indicator clearly constitutes “inappropriate use of journal-based metrics”. With all this history, it came as a shock to many when earlier this year, one of the DFG panels deciding which grant proposals get funded, published an article in the German LaborJournal magazine that seemed to turn the long, hard work of the DFG in this area on its head. The panel starts by making the following statements (my translation of sentences 2-4):

Our panel evaluates grant proposals in all their dimensions and one such dimension is the qualification of the applicant by their publication record. In a changing [publication] landscape, it is not easy to choose the right journal for the publication of research results. In this regard, we would like to share some thoughts, such that your publication strategy may match the expectations of decision-making panels.

It seems obvious that in this order, these sentences send this message:

- We decide grants by looking at publication records

- We use publication venue for #1

- You better follow our guidelines of where to publish if you want to meet our expectations (and that of other panels) to get funded.

Which is pretty much the opposite of what DORA and CoARA are all about and what the DFG says in their own position paper. Or, phrased differently, if this article were compatible with DORA, CoARA and the DFG position paper, neither of the three could be taken seriously any more. At the time of this writing, the DFG has not publicly responded, neither to personal alerts about the article, nor to DORA and CoARA which have also contacted them. At the very least, the DFG does not see the article as worrisome enough for a swift response – and this is troubling.

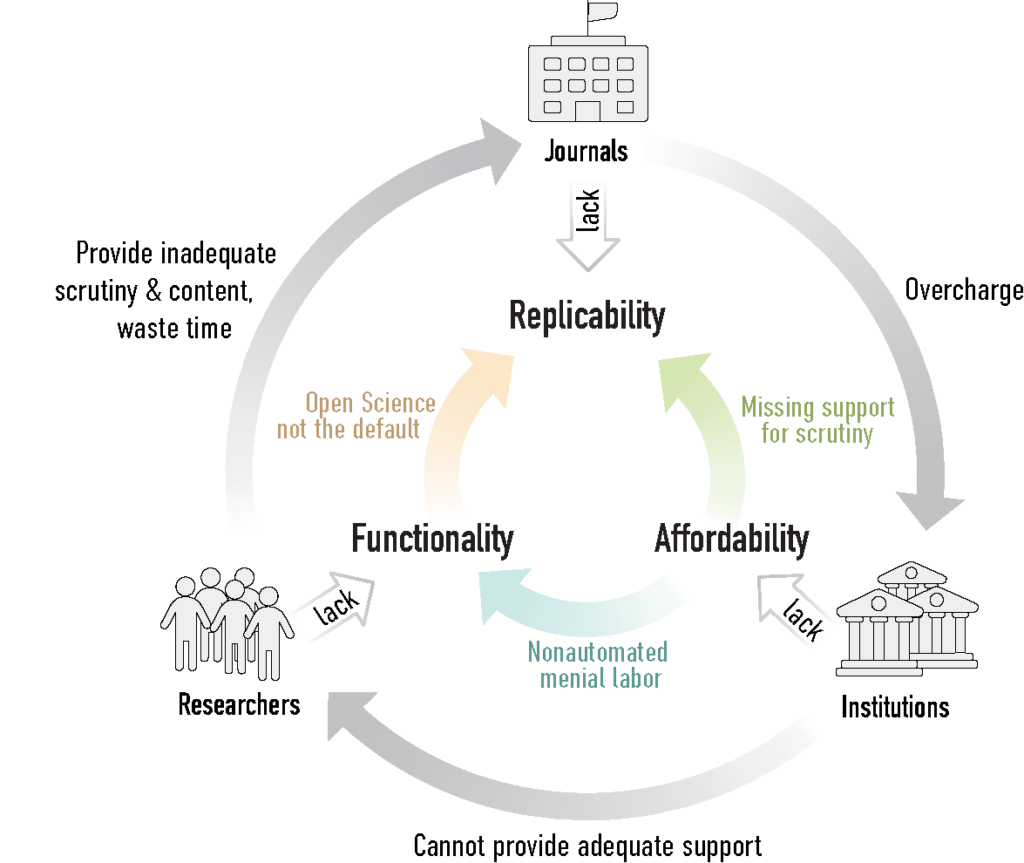

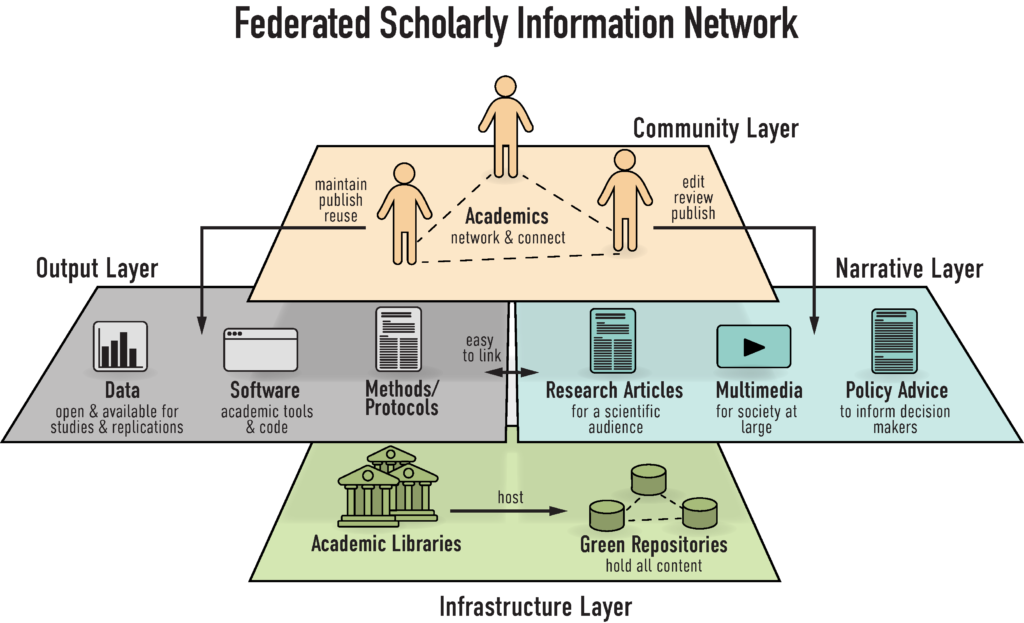

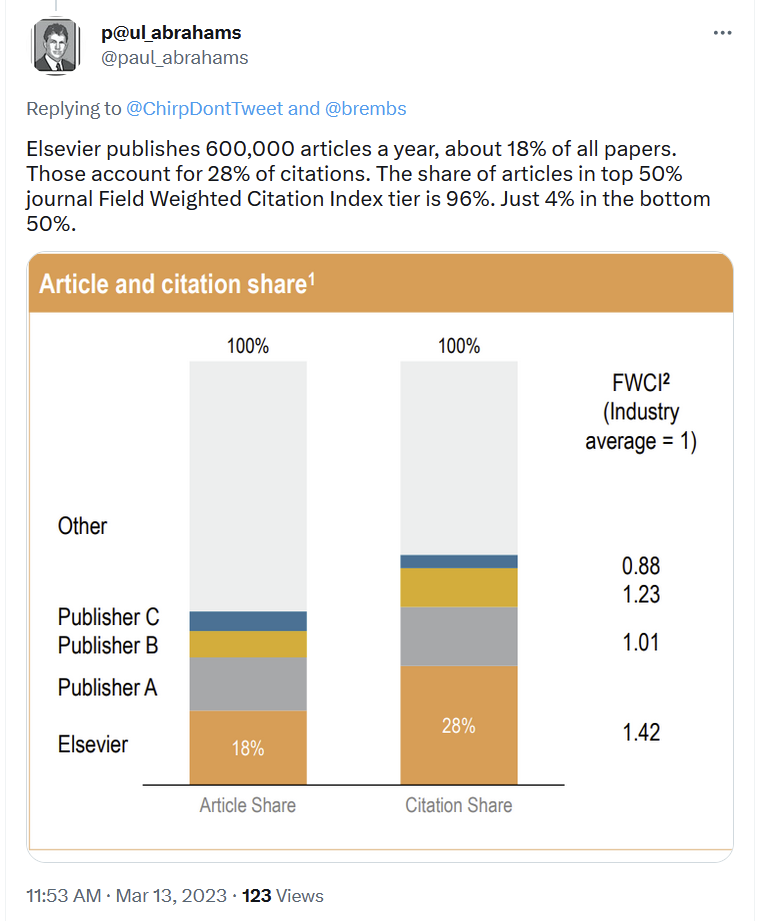

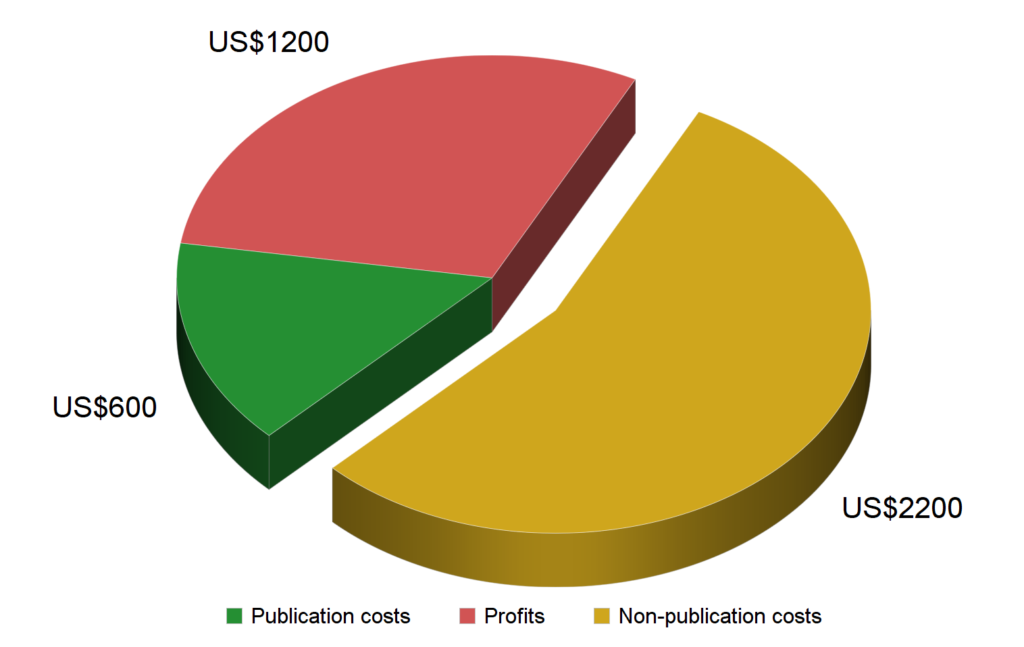

One less worrisome explanation for this slow reaction could be that this is just one panel in a large institution and the DFG has more important things to worry about. After all, both their position paper and in their press release, they support the plans of the EU Council of science ministers’ proposal to fund an open scholarly infrastructure instead of monopolistic publishers, i.e., the plan is to have this infrastructure replace academic journals. This is obviously a major undertaking and one that also requires research assessment to change. So maybe, with limited resources, the DFG is prioritizing the larger goal over mere research assessment? This explanation does not seem very likely: last week, the news broke that the DFG plans to join the recent DEAL agreement with data analytics corporation Elsevier. Similar to the article by the panel, this contract also embodies pretty much the opposite of DFG’s own stated goals, in this case one of establishing “open access infrastructures located at research organisations that operate without publication fees payable by authors and are not operated for profit.” The many reasons why entering this contract is a mistake have already been listed elsewhere. Here, the important aspect is that this decision would be already the second time this year that DFG practice is in direct opposition to their policies.

What could possibly be the reason for this sudden and very recent inconsistency between officially stated policies and actual practice at the largest German funder after so many years of very consistent development? Apparently, it was the DFG’s Board, led by president Katja Becker (since 2020), that forced the decision to join the Elsevier DEAL over the objections of expert committees. What could possibly have motivated the Board to side with the corporate giant Elsevier against not only their own scholarly expertise, but also their own public policies?

Both DORA/CoARA, if widely implemented, would weaken the stranglehold corporate publishers exert over public knowledge and as such would help pave the way for a publicly owned, not-for-profit scholarly infrastructure for said knowledge. With this overarching goal in mind, the public statements by the DFG are internally consistent over many years and appear competent, logical, coordinated and scholar-led. In this regard, the DFG sets an example for funding agencies world-wide. In fact, the EU-supported CoARA was, in part, designed to help support the plan by the EU science ministers for a scholarly infrastructure avoiding corporate vendor lock-in. All of this constitutes a paragon of evidence-based policy-making and stands to negatively affect current corporate publishers. As such, it is safe to assume that these corporate publishers interpret these public policies of the DFG as another threat to their parasitic business model. From this perspective, both the admonition to publish in “good” journals (read: in journals predominantly published by corporate publishers) and the decision to join the Elsevier-DEAL are decidedly publisher-friendly, propping up the status quo and delaying any modernization. Why would the DFG-Board, then, act in such a publisher-friendly way, when the DFG public policies are anything but?

Nobody but the Board members themselves can know this, of course. However, in the last few days, individuals with personal knowledge have been privately pointing to connections between the DFG president, Katja Becker, not only with Stefan von Holtzbrinck (whose company not only owns SpringerNature but also DigitalScience), but also with Elsevier CEO Kumsal Bayazit. Given the DFG’s public policies, both would be expected to voice strong opposition, when given a chance to speak in private with the president of the DFG, one would suppose. Or, alternatively, has the DFG become such a big and unwieldy organization that simply the left hand doesn’t know any more what the right hand is doing? Whatever the reason, this sudden inconsistency is troubling and the potential consequences pernicious. Many applicants, at least, would probably sleep better if this inconsistency were resolved.