To my knowledge, no neuroscientist hypothesizes that there is magic in our heads. However, it appears this is a hypothesis that flies by the editors at the New York Times. The title of this op-ed piece says it all: “beyond the brain”. The author, David Brooks, claims: “The brain is not the mind.” Last I looked (which was a few seconds ago, I admit), beyond the brain was the Pia mater, the subarachnoid space, the Arachnoid, the dura mater and the skull. I wonder, just where precisely does the magic mind sit, if it’s not the brain? In the subarachnoid space, squeezed between layers of connective tissue and blood vessels? Or is it even beyond the skull, hovering above our heads? Now, Mr. Brooks doesn’t mention the Psychokinetic Energy Meter, but he makes it sound as if in his world this is the scientific instrument with which one would measure the capacity of the mind to move the body. Probably most disappointingly, Mr. Brooks bolsters his magic-mind hypothesis with the classic argument from incredulity: ‘I don’t understand it, so it must be magic’: “It is probably impossible to look at a map of brain activity and predict or even understand the emotions, reactions, hopes and desires of the mind.” This is like saying “it’s probably impossible to build a heavier-than-air flying machine” before the Wright brothers’ first flight. More disturbingly, it’s like saying: “I don’t understand no evilution, therefore magic man dunnit”.

Mr. Brooks caps his magic-mind hypothesis off with a few short paragraphs essentially saying “we have free will because I think so, free will is magic, so there’s magic in the head – and science is too limited to get into magic, don’t you forget that!” Given that his main point is that the mind is magic, one can only assume that he means neuroscience is too limited to understand free will sort of like medicine is too limited to understand homeopathy and physics is too limited to understand astrology. This final point is probably the only accurate statement of the entire piece: magic in the head is about as thoroughly debunked as homeopathy or astrology.

What we call ‘mind’ exists in a similar way as colors exist: our brain creates it. Colors are real in the sense that our brain makes colors real, it constructs a reality with colors, but spectral properties of light are not colors. Just like colors, the mind, free will, are real, but not in the way Mr. Brooks apparently thinks: they’re not magic. Neural activity makes our minds just as real as colors, but neither are magic nor do they exist outside of our heads. The fact that we don’t understand, yet, how the brain does that, is not a valid reason to explain our ignorance away with magic, but a boon to neuroscientists (or we’d be unemployed). The correct answer to the question: “what is the mind?” is not “magic”, but “we don’t know how, but all the evidence says it’s our brain that somehow creates it”.

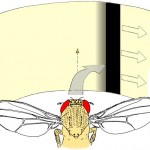

This very fundamental insight of the last 40 years or so of neuroscience, obviously entails that with every discovery we will be better able to predict future actions. If that seems disappointing, tough luck, live with it. Today, we clearly cannot “take pretty brain-scan images and […] use them to predict what product somebody will buy”, this is pop-neuroscience. However, much like we got better at predicting the weather by studying it, we will get better at predicting future actions by studying the brain – as we have already become much better over the last decades. Importantly, and I cannot stress this enough, we don’t need magic to understand that we will nevertheless, not even with unlimited time and resources, never be able to fully predict human behavior. Just like no neuroscientist postulates magic in our heads, no meteorologist would postulate that it’s magic that prevents us from making accurate weather forecasts and no astrophysicist would claim that magic messes with Pluto’s unpredictable orbit. Apparently, it will take a few more decades until it sinks in that the brain is a little more complex than the weather or our solar system. Anybody who thinks that the brain needs magic to bring about the mind with free will thoroughly underestimates it. Everybody and their grandma today has already realized that complex nonlinear dynamics (“butterfly effect”, “chaos” – coincidentally coined in the same decade that dualism essentially died) prevent accurate weather forecasts on a principle basis, not out of technical problems. These effects even make the orbit of Pluto unpredictable! The data from brain recordings and behavioral studies show mathematically analogous nonlinearities, which lead to the predictability of behavior to decay exponentially with the forecasting period even in flies. Clearly, one can assume that humans are less nonlinear and more predictable than flies as apparently Joshua Greene at Harvard seems to postulate, but even as a fly researcher, I find that somewhat hard to accept. But hey, what does a fly guy know? Be that as it may, as long as humans are equally or less predictable than fruit flies, the data from our own little lab alone already alleviate Mr. Brooks’ fears: brains will not become fully predictable with more neuroscience, only gradually more so.

It seems there is a deep-seated frustration that science explains away magic, even in otherwise science-o-phile individuals. More and more research (some of it reviewed here) is accumulating that demonstrates that not only our flies, but many, perhaps all animals have the capacity, given the right circumstances, to make different decisions under identical circumstances. In fact, as has often been argued (review here) before, such protean behavior is a prerequisite and an inevitable outcome of evolution. Why should animal brains possess this capacity and human brains not? If this kind of free will disappoints you, tough luck, live with it. Free will is the capacity of the brain to make decisions that are influenced by all the events leading up to the decision, but not determined by them. Free will is a brain capacity that is of course determined by neural activity, but the neural activity is no more deterministic than the weather is. In fact, I would postulate that our brains are even less deterministic than the weather. Call it wiggle-room, or elbow room, the nonlinearity of decision-making relegates the question of just how deterministic the brain really is to a (highly interesting!) academic debate: in practice, brains will always be less predictable than the weather, irrespective of any quantum effects playing a role or not. This modern, scientific concept of free will emphasizes that our freedom can of course not be absolute. Freedom is always a matter of degree, of shades of gray between the blacks and whites of determinism and stochasticity. In fact, this is precisely how such nonlinearities operate, by implementing deterministic and stochastic components to create phenomena that are neither fully deterministic nor completely stochastic. As we understand the deterministic components better, we get better at predicting nonlinear behavior, but the very nature of all of these systems fundamentally prevents fully accurate forecasts. In reality, we create robots with free will, we even start to understand the neurophysiological mechanisms by which neural processes become unpredictable, but Mr. Brooks writes in the NYT that because he doesn’t understand how the neurons are doing it, it must be magic.

For the life of me, I have no idea what is getting into people like Mr. Brooks who at least give off the very succinct impression that they fear that the human brain needs magic, or else we might one day understand it too well for our own good. Have they no respect for the lump of tissue between their ears? At least he gets a thorough bashing in the many of the comments and of course by the inimitable Neurocritic.

One of our graduate students might have just discovered the neural circuit that allows fly brains to decide which way to turn, even in a virtual environment without any cues. Now please excuse me while I go back to explaining away some magic by studying fly neurons.

Like this:

Like Loading...