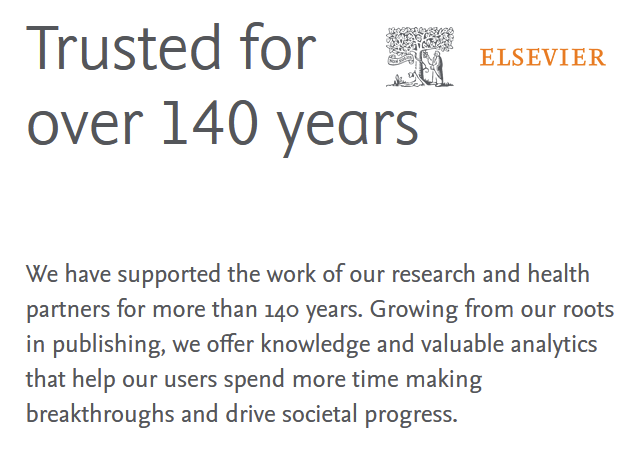

Data broker RELX is represented on Twitter by their Chief Communications Officer Paul Abrahams. Due to RELX subsidiary Elsevier being one of the largest publishers of academic journals, Dr. Abrahams frequently engages with academics on the social media platform. On their official pages, Elsevier tries to emphasize that they really, really can be trusted, honestly:

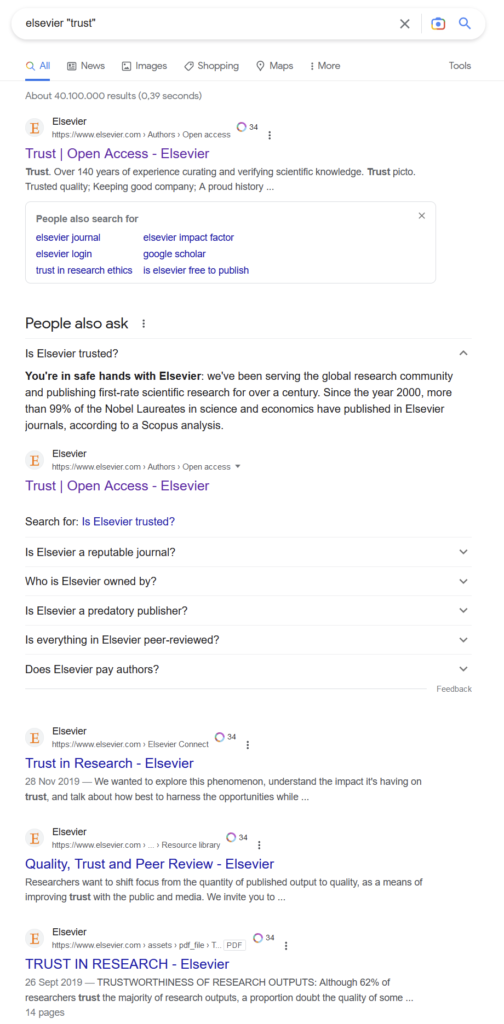

In fact, if one searches for “trust” with Elsevier, one may be forgiven for getting the impression that Elsevier is obsessed with trying to appear as if they were trustworthy:

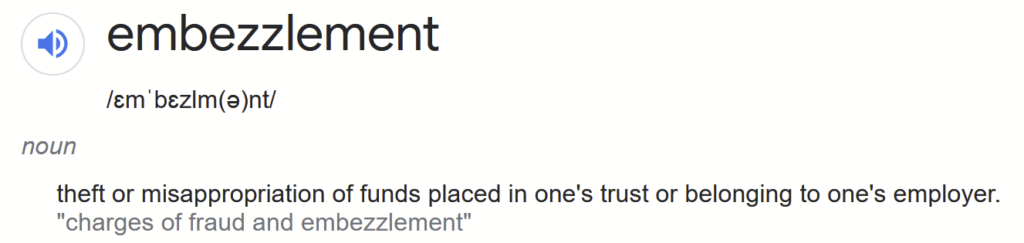

For anyone following Elsevier’s endless list of transgressions, is not difficult to understand this obsession: academics routinely call the company “Evilsevier” for more reasons than there are bits on the internet (see, e.g., their Wikipedia page). With so many parasitic or outright hostile actions consistently directed at academics and academic institutions over decades, it really is prudent to at least try and provide an outwardly trustworthy face to the unsuspecting early career researcher who may not have heard of ‘Evilsevier’, yet. A wolf in sheep’s clothing:

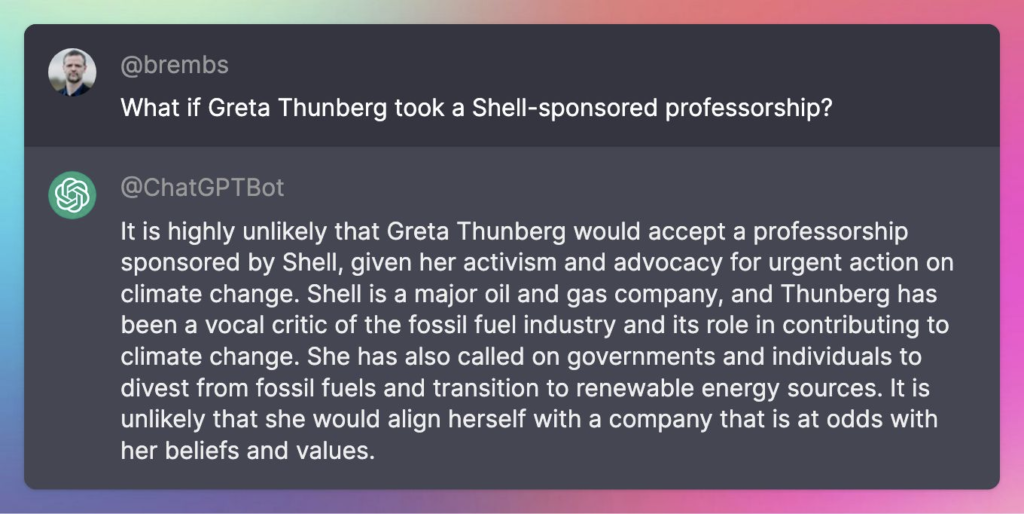

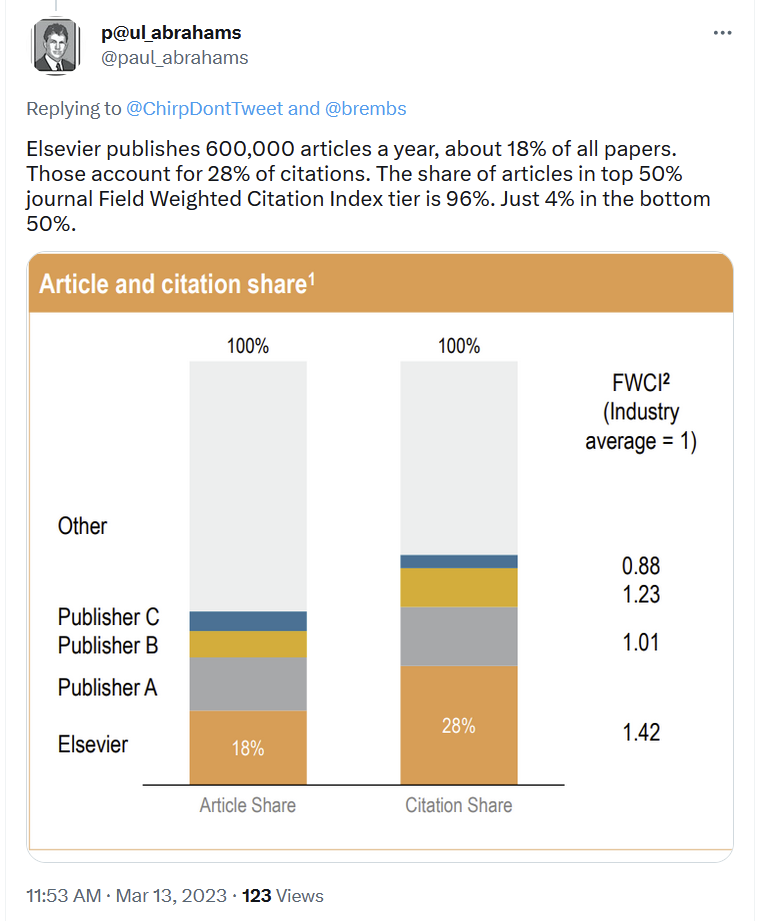

The fact that Elsevier fits the consensus definition of a “predatory publisher” so well is thus only one of many reasons why data kraken Elsevier is so reviled in the academic community, but a reminder of it seems to have triggered the “we really can be trusted, honestly, this time” wolf-in-sheep-clothing-reflex in the RELX CCO Dr. Abrahams, such that he responded:

Apparently, he tried to make the claim that so many researchers author in and cite Elsevier journals that this must be evidence they trust Elsevier. He went on to make three very specific claims, which are worth examining:

As Paul Abrahams is tweeting in his capacity as “Chief Communications Officer at RELX”, let’s fact-check his three statements, one by one, as an example of just how trustworthy such public statements from RELX/Elsevier can be.

1. “Elsevier provides above-average quality…”

Let’s pretend, for now, RELX were not chiefly a surveillance platform and data broker enabling ICE mass deportations (some quality!), but instead an academic publisher (via subsidiary Elsevier) with above average overall impact (according to the citation numbers Dr. Abrahams posted himself, see above). In that case, given the negative relation between impact/prestige and quality, the available data suggest that Elsevier actually provides *below average* quality. So the first statement is contradicted by the available evidence. Of course, it may also be that Elsevier journals aren’t as impactful as their CCO claims, in which case his previous statement would be false. Either way, both cannot be correct at the same time.

2. “…for below average prices”

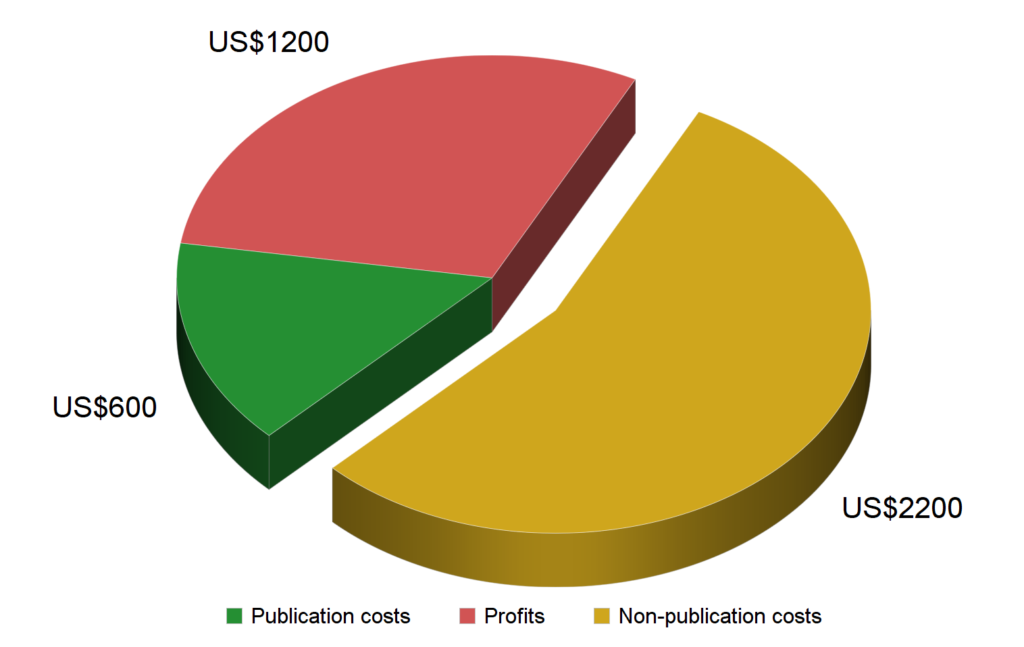

From the Q&A on occasion of the release of the latest 2022 RELX financial statement, and from Dr. Abraham’s tweet above, we learn that Elsevier published 600,000 articles the past year yielding a revenue of 2,909 £ million. Accordingly, an average article from Elsevier cost the tax payer 4,848£ or US$5,850. Which, even if one assumes the upper bound average cost of an article at US$5,000, is more than average. Also the second statement can be easily falsified, this time using RELX’s own numbers.

3. “You just don’t think the private sector should be involved in the diffusion of scholarly knowledge.”

Let’s take a recent article on the topic with me as a co-author and check the abstract: “It [the journal replacement] needs to replace the monopolies of current journals with a genuine, functioning and well-regulated market. In this new market, substitutable service providers compete and innovate”. Quite demonstrably, we argue for a market and the article text clearly states “traditional businesses” as competing as service providers in this market. So also this statement is obviously false. Interestingly, Paul “Chief Communications Officer at RELX” Abrahams seems to interpret our proposal of a “genuine market” as a threat to their monopoly and rightfully so: an actual market does threaten Elsevier’s gargantuan profit margins (37.8% in 2022, see above financial statement) with competition, something they fear deeply, as they have never had to deal with it in the history of their company. Quite apparently, Elsevier fear the mere proposal of competition so much, they attempt to smear it with misrepresentations by the Chief Communications Officer of their parent company.

So all three statements by the CCO of RELX turned out to be demonstrably false. Not surprising for the most reviled corporation in academia, where probably one of the least damning qualities is that they also fit the consensus definition of a predatory publisher. If Paul Abrahams keeps his job (as one would strongly suspect), it only serves to confirm that such false statements are part and parcel of the strategy with which RELX communicates with academics – and that one should never assume any engagement with them will be in good faith.