tl;dr: Evidence suggests that the prestige signal in our current journals is noisy, expensive and flags unreliable science. There is a lack of evidence that the supposed filter function of prestigious journals is not just a biased random selection of already self-selected input material. As such, massive improvement along several variables can be expected from a more modern implementation of the prestige signal.

Some common responses to the proposal to replace the now more than 35,000 peer-reviewed scholarly journals with more modern solutions are “Why do you want to get rid of peer review?” or “How should we know what to read without journals?”.

Both, of course, imply insufficient engagement with the proposal and its consequences. As for the first question regarding peer-review, there is currently very little evidence as to the cost-effectiveness of peer-review and most comparisons between un-reviewed ‘preprint’ manuscripts and the published articles after peer-review, show few substantial differences. Given the huge costs associated with peer-review, one would expect peer-review effectiveness to increase dramatically by modernizing the way it is organized and deployed. As this conclusion and expectation is not new, the literature is brimming with suggestions for improving peer-review, just waiting to be tested. The proposal to replace journals specifically includes a more effective way to leverage the power of peer-review.

The second question implies two implicit assumptions, namely that the prestige inherent in journal rank carries a useful signal and that this signal is actually being commonly used when making decisions about which portion of the scholarly literature to read. Let’s see if there is evidence supporting these assumptions.

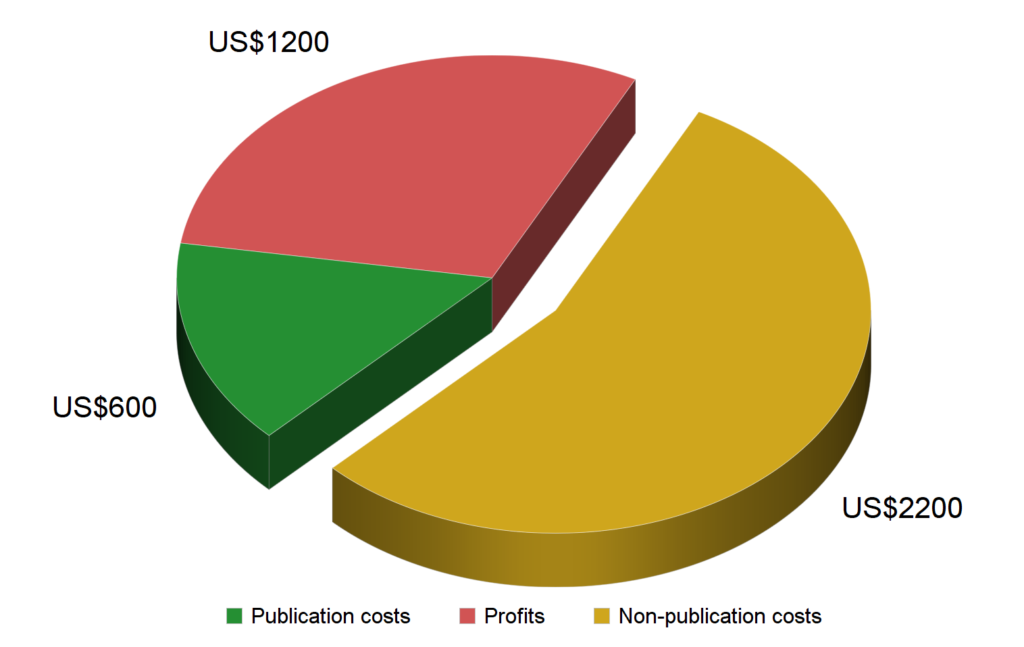

There is some evidence in the literature (review of a subsection) that there indeed is a signal conveying more ‘novel’ or ‘breakthrough’ discoveries in the more prestigious journals. However, this literature also emphasizes that the signal to noise ratio is very poor: it contains many false-positives (articles that turn out to be not particularly novel or ground-breaking) and false-negatives (many novel and ground-breaking discoveries are first published in lower ranking journals). Unfortunately, because of the nature of journal publishing, the full extent to which the false-negatives contribute the noise in the signal cannot be known, as it is commonly not known which submissions have been rejected by any given journal (more about that later). Adding insult to injury, this already noisy signal is then degraded even further by the reliability of the signal being no higher (in fact, slightly lower) than in average journals. This means that more of the published articles in prestigious journals, even those that are novel or signify a break-through, turn out to be irreproducible or contain more errors than articles in average journals. Finally, this weak signal is then bought at a price that exceeds the costs of producing such a scholarly article by about a factor of ten. Thus, in conclusion, the prestige signal is noisy, the science it flags is unreliable and the moneys it draws from the scholarly community exceed the cost of just producing the articles by almost an order of magnitude.

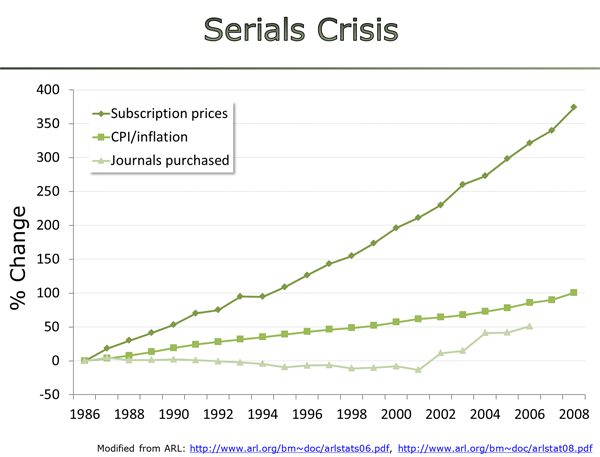

It may thus be of little surprise that one can find evidence that this noisy signal that tends to also flag unreliable science does not seem to be used as commonly by readers as it is sometimes claimed. Unfortunately, there is no direct evidence as to how readers use the scholarly literature, in part, again, because our literature is fragmented into 35,000 different journals. Therefore, currently, we are forced to restrict ourselves to citations as a proxy for reading: one can only cite what one has also read. Using the signal of journal rank (as routinely and reliably measured by impact factor), Lozano et al. predicted subsequent citations to published articles. In other words, the authors tested the assumption that journal rank signals to readers what they should read and, consequently, cite. When looking at it historically (figure below), this predictive power of journal rank starts surprisingly low, but statistically significant, due to the authors analyzing millions of articles.

As the serials crisis starts to hit in the 1960s/70s and libraries are forced to use the impact factor to cancel subscriptions to low-ranking journals, this predictive power, not surprisingly, starts to increase, if ever so slightly: you really can only cite what you can read. The advent of keyword searches and online access then abolishes this modest increase and today, the predictive power of journal rank on citations/reading appears to be as low as it ever was. Given that citations to articles in prestigious journals are often used by authors to signal the importance of their topic, even these low numbers are probably overestimating the true effect of journal rank on reading decisions. So there seems to be an effect of prestige on citations/reading, but it is very weak, indicating that either only very few readers are using it or each reader is not applying it very stringently. In other words, the low predictive value of journal rank on future citations can be considered a reflection of users realizing that the publication venue contains little useful information when making choices about what to read.

Noticing an apparent disconnect between these citation data and the fact that journal rank is partly based on citations, Pedro Beltrao pointed to a different study, where high impact factor journals, on average, tend to be enriched in papers that will be highly cited in the future, comparing the slice of 1% most highly cited papers. However, these results only superficially seem to be in contradiction to the data presented by Lozano et al. In fact, I would argue that the 1% study actually supports the interpretation that journal rank is only very rarely used as a signal of what to read or cite: because there are more “novel” or “break through” papers in these journals (as detailed above), people will cite these rare 1% papers more often. But that effect hardly changes the probability of the remaining 99% of papers to be cited. These papers are ‘regular’ papers that could have been published anywhere. This evidence thus suggests that readers decide what they cite not based on containers, but based on content: the 1% of articles in prestigious journals that are actually novel and ground-breaking are cited more, and the other 99% are cited just as much as articles in any other journal. In fact, this insight is corroborated when comparing citation distributions between journals.

All of this evidence supports the interpretation that yes, there is a signal in journal rank, but it mainly comes from a very low percentage of the papers (that then, in turn, is less reliable than average) and hardly translates to the vast majority of the papers in prestigious journals at all: the effect is almost gone when you include all papers. Therefore, arguably, the little effect that remains and that can be detected, is likely not due to the selection of the editors or reviewers, but due to the selection of submission venue by the authors: they tend to send their most novel and break-through work to the most prestigious journals. The fact that what we think is our most novel and groundbreaking work is too often also our worst work in other aspects, probably explains why the reliability of publications in prestigious journals is so low: not even the professional editors and their prestigious reviewers are capable of weeding out the unreliability.

Taken together, despite the best efforts of the professional editors and best reviewers the planet has to offer, the input material that prestigious journals have to deal with, appears to be the dominant factor for any ‘novelty’ signal in the stream of publications coming from these journals. Looking at all articles, the effect of all this expensive editorial and reviewer work amounts to probably not much more than a slightly biased random selection, dominated largely by the input and to probably only a very small degree by the filter properties. In this perspective, editors and reviewers appear helplessly overtaxed, being tasked with a job that is humanly impossible to perform correctly in the antiquated way it is organized now.

Unfortunately, given the current implementation of the prestige signal by antiquated journals, it remains impossible to access the input material and test the interpretation above. If this interpretation of the evidence were correct, much would stand to be gained by replacing the current implementation of the ‘prestige signal’ with a more modern way to organize it.

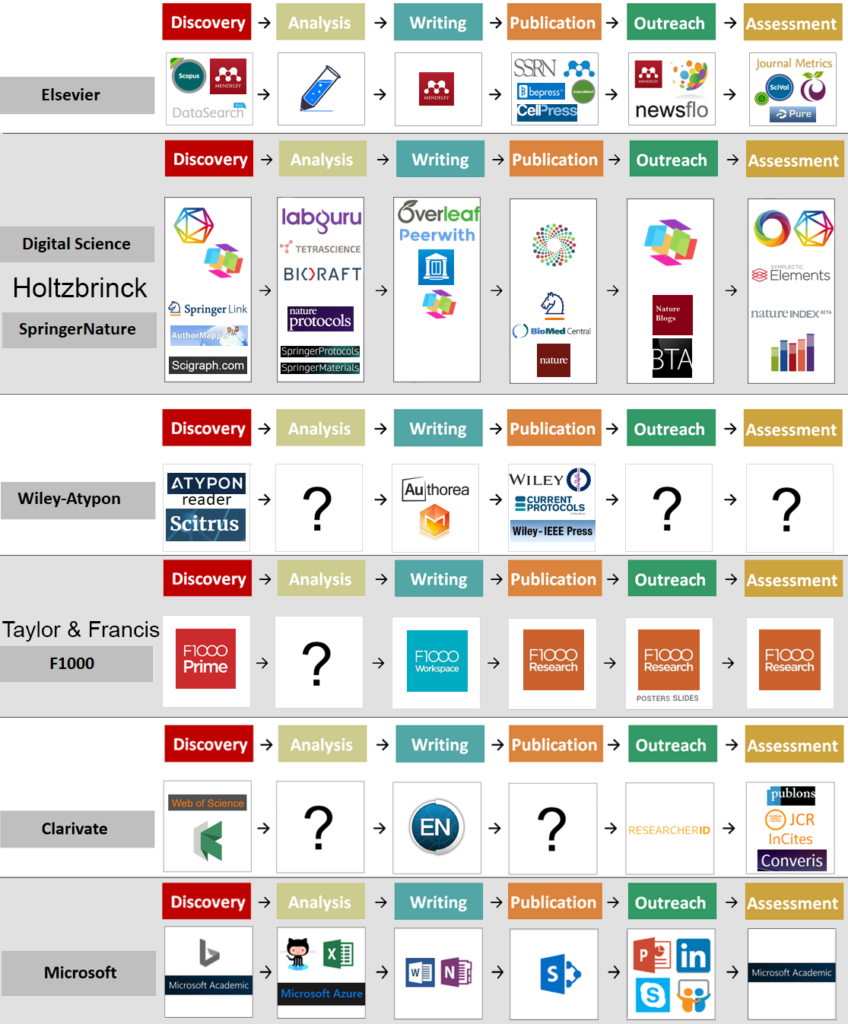

How could a more modern system support a ‘prestige signal’ that would actually deserve the moniker? Obviously, if journals were to be replaced by a modern information infrastructure, only our imagination is the limit for which filters the scholarly community may want to implement. Some general ideas may help guide that brainstorming process: If the use of such ‘prestige’ not only in career advancement and funding, but also in the defense of the current system is anything to go by, there should be massive demand for a prestige signal that was worth its price. Today, this prestige arises from selectivity based on expertise (Nature’s slogan always was “the world’s best science”). This entails an expert-based filter that selects only very few (‘the best’) out of of the roughly 3 million peer-reviewed articles being published each year. Importantly, there is no a priori need to objectively specify and determine the criteria for this filter in advance. In a scenario after all journals had been replaced by a modern infrastructure for text, data and code, such services (maybe multiple services, competing for our subscriptions?) need only record not just the articles they selected (as now) but also those they explicitly did not select in addition to the rest that wasn’t even considered. Users (or the services themselves or both) would then be able to compute track records of such services according to criteria that are important to them.

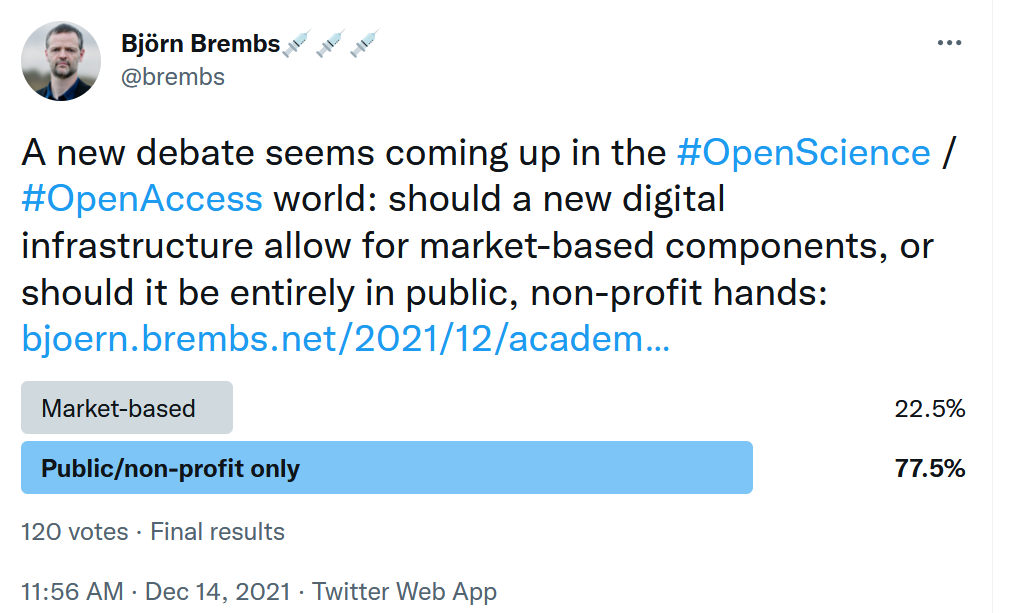

Mimicking current implementations, e.g., the number of citations could be used to determine which service selected the most highly cited articles, how many it missed and which it falsely didn’t even consider. But why stop at bare citations? A modern infrastructure allows for plenty of different markers for scholarly quality. One could just as well use a (already existing) citation typology to differentiate between different types of citations, one could count replications, media mentions, anything, really, to derive track records by which these services may be compared. Given the plentiful demand indicated by the fervent supporters of prestigious journals, services would compete with each other using their track records for the subscriptions of individual and institutional users, providing for innovation at competitive prices, just like any other service market. Such an efficient, competitive marketplace of services, however, can ever only arise, if the current monopoly journals are replaced with a system that allows for such a market to be designed. If demand was not as high as expected, but such a signal nevertheless desired by some, a smaller, more basic implementation could be arranged on a non-profit, open source basis, funded by the vast savings that replacing journals would entail. One may also opt to hold competitions for such services, awarding prizes to the service that best serves the needs of the scholarly community. The possibilities are endless – but only once the scholarly community finds a way to put itself into a position where it has any power over the implementation of its infrastructure.

Perhaps most importantly, such a modern implementation of the prestige filter offers the promise of actual consequences arising from the strategies these prestige services employ. Today, publishing articles that later turn out to be flawed has virtually no tangible consequences for the already prestigious journals, just as a less prestigious journal can hardly increase its prestige by publishing stellar work. With power comes responsibility and our proposal would allow the scholarly community to hold such services to account, a feat virtually impossible to reach today.

P.S.: Much like the ideas for replacing journals have been around for decades, the ideas for replacing prestige signals have been discussed fro a long time. There is a post from Peter Suber from 2002, and there is one of my own from 2012.