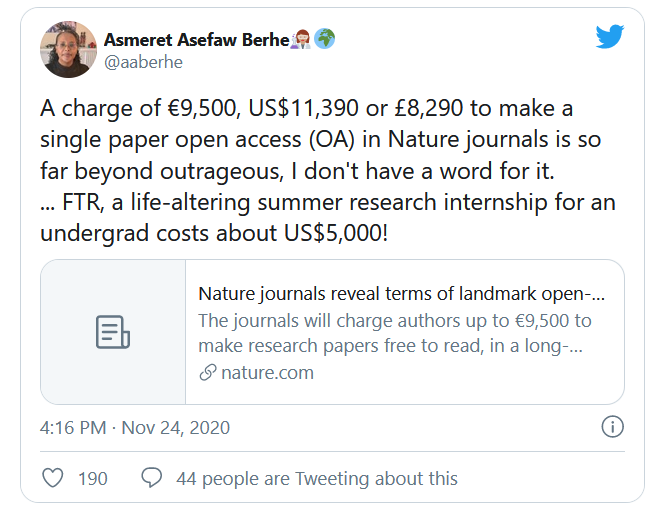

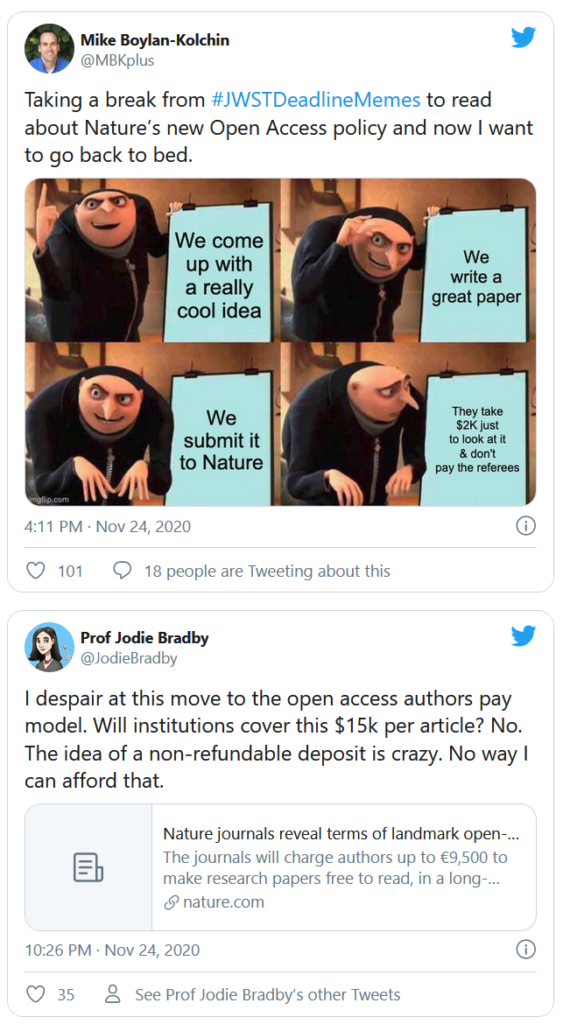

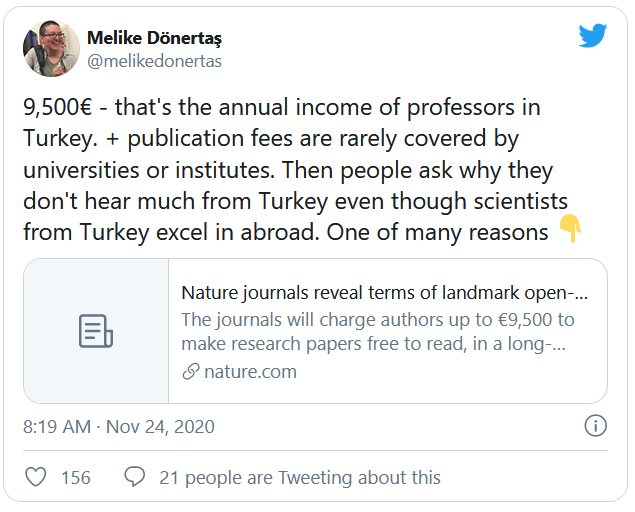

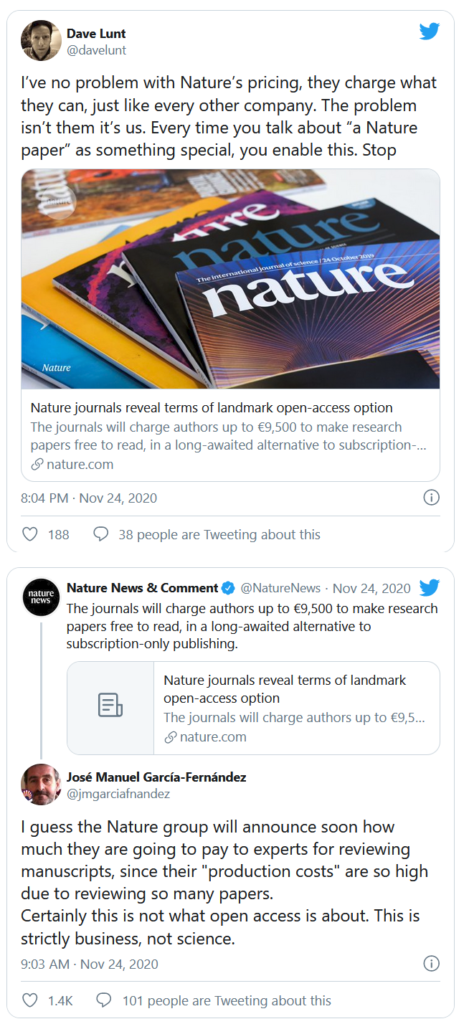

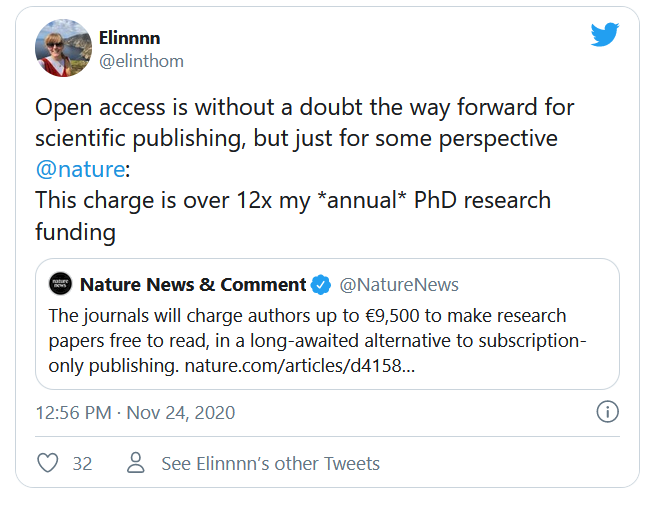

Last week, there was a lot of outrage at the announcement of Nature’s new pricing options for their open access articles. People took to twitter to voice their, ahem, concern. Some examples:

There are many more that all express their outrage at the gall of Nature to charge their authors these sums,. even Forbes interviewed some of them. At the same time, the people who have been paying publishers these sums for decades find that the ~10k per paper is actually “very attractive” and “not a problem”.

So which is it? Are Nature’s APCs ‘outrageous’ or are the prices ‘very attractive and not a problem’?

What is clear is that these charges are definitely not a surprise. Already back in 2004, in a Parliamentary inquiry in the UK, Nature provided testimony that they would have to charge 10-30k for a Nature paper, given their revenues at the time (i.e., their subscription and advertising income). While back then, most people scoffed at the numbers and expected that no author would ever pay such fees, Nature got to work and invented a whole host of ‘lesser’ journals (i.e., Nature XYC as in “Nature Physics”, Nature Genetics” and so on), which would serve several purposes at once: They increase revenue. As hand-me-down journals they keep desperate authors attached to the Nature brand. As less selective journals, they would bring down average costs per article for the brand total, when they would need to go open access.

So this year, after open access advocates, funders and the now also pandemic-stricken public had kept demanding open access for 16 years after they had been warned, Nature was finally ready to deliver. Due to the dilution of their costs by way of the ‘lesser’ journals, they managed to keep their APCs close to their lower bounds of 2004, despite 16 years of inflation. Given that libraries have been paying these kinds of funds for Nature journals for decades, this price tag then really is a bargain, all things considered.

Given this analysis, all the online outrage strikes me as unwarranted. While I of course agree that it should have never come so far (we ought to have realized where this is headed already in 2004!), crying foul now comes about 16 years too late. We have had plenty of time to prepare for this, we have had more than enough time to change course or think of alternative ways to the legacy publishers. And yet, nearly everybody kept pushing in the same direction anyway, when we could have known in 2004 that this was not going to end well. The people warning of such not quite so unintended consequences were few and far between.

Having only gotten interested in these topics around 2007 or so myself, it took me until 2012 to understand that this kind of APC-OA was not sustainable and, indeed, would stand to make everything worse just in order to worship the sacred open access cow.

If you were even later to the party and are outraged now, direct your outrage not to Nature, who are only following external pressures, but to those who exert said pressures, such as open access advocates pushing for APC-OA and funders mandating authors to publish in such journals.