Until the late 1980s or early 1990s, academic institutions such as universities and research institutes were at the forefront of developing and implementing digital technology. After email they developed Gopher, TCP/IP, http, the NCSA Mosaic browser and experimented with Mbone.

Since then, at most academic institutions, infrastructure has moved past the support of email and browsers only at a glacial pace. Compared to the years and decades before the early 1990s, the last 30 years appear to be frozen in time, with virtually no modernization of our infrastructure beyond bandwidth.

Functionalities we take for granted outside of academia, such as automated data sharing, collaborative code development and authoring, social media, etc. – virtually none of it is supported by academic institutions on an analogous, broad international scale such as email or browsing.

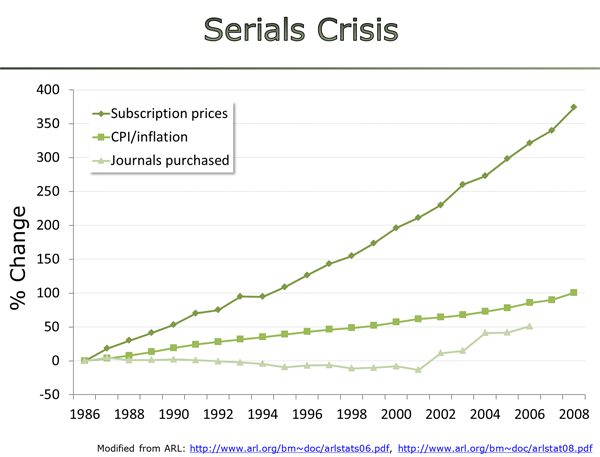

As the technology is commercially available and more than enough money is still flowing into obsolete infrastructure such as journal subscriptions, the conclusion that it must be a social obstacle that prevents infrastructure modernization becomes inescapable.

I was asked on Twitter today, what this social obstacle might be and how it could be overcome:

Here is a short summary of my answers to these two questions:

The first is a difficult question and I only can offer hypotheses. A recent comment by Antonio Loprieno when we were on a panel of the German Wissenschaftsrat, seemed to confirm part of one hypothesis: he said, citing a recent example from a university in Germany, that today institutions seem to be more willing to invest in looking like they are performing better, rather than to actually perform better – show over substance. His example was that of a university hiring two FTEs to massage the data sent to ranking organizations, rather than to change the way the university is operating.

From this perspective, until the early 1990s, around which time universities were told to compete, universities cooperated and had the interest of their faculty and students in mind. This entailed that if there was a technology that would stand to improve how the university could fulfill its mission and money was available to implement it, it would be implemented. The internet was such a technology and according to a book entitled “How not to network a nation“, institutions had to cooperate to make this technology a reality. Apparently, academic institutions saw the potential, found the money and cooperated, or the efforts would have failed just as those in the Soviet Union at the time failed.

Analogous to the failure of Soviet Russia to use competition between institutions to develop their own network, roughly since the fall of the iron curtain (ironically enough) we have been mimicking the failed Soviet approach with competing institutions focusing more on rankings rather than actually improving the way they pursue their mission.

As for the second question, of how to overcome this social obstacle, this is easier to answer and there are a number of options to choose from.

- Obviously, one could revert some of the fatal decisions made in the early 1990s (like getting rid of New Public Management and other similarly embarrassing inventions).

- However, #1 seems like the most difficult of options, so almost a decade ago now, I thought one only needed to convince libraries that they are ideally suited to implement the new infrastructure as they have both the expertise and, of course they control the money. After nearly a decade of interacting with both skeptical and enthusiastic libraries, I can now see why even the enthusiastic ones are hesitant: they have similarly good reasons not to act as my researcher colleagues.

- So when I saw how deans of several departments here at my institution were scrambling to find positions and money for infrastructure requirements of the DFG, I had the idea for Plan I (for infrastructure): these infrastructure mandates that are already in place for some aspects of funding, need to be expanded for all aspects. Institutions dependent on research overhead will do anything to meet the demands of the funders, as I could experience first hand. I’ve talked to funders like the DFG, NSF, NIH and ERC (Bourguignon) and none of them saw any obstacles, but I have yet to see adoption or even widespread discussion.

So given that last experience and those of the last 13 years or so in which I have been involved in these topics, I expect funders to soon come up with a similar reason as my researcher colleagues and libraries as to why they actually do support infrastructure modernization, but, unfortunately, can’t do anything about it other than to keep hammering down on the least powerful (e.g., with individual mandates) and let the main obstacles to modernization remain in place.