![]() This year’s Winter Conference on Animal Learning and Behavior (WCALB) will be on one of my oldest and most central research projects, the commonalities and differences between operant and classical conditioning. I picked this project for my Diploma (Master’s) thesis way back in 1995, because I had learned about these forms of conditioning in high-school and couldn’t believe it when I heard that nobody knew how the brain was doing it.

This year’s Winter Conference on Animal Learning and Behavior (WCALB) will be on one of my oldest and most central research projects, the commonalities and differences between operant and classical conditioning. I picked this project for my Diploma (Master’s) thesis way back in 1995, because I had learned about these forms of conditioning in high-school and couldn’t believe it when I heard that nobody knew how the brain was doing it.

Little did I know back then, that already in the 1930s B.F. Skinner and the students of Ivan Pavlov, Konorski and Miller, had started discussing how operant and classical conditioning are similar and how they differ. It wasn’t until I had started my PhD on this topic, that I had found these gems in the dusty bound volumes of our library. Many of the arguments and questions raised in this soon 80 year-old exchange became the basis for my research program in the following now almost 20 years. When I embarked on this project, six decades had already passed with significant progress, but without answers to these fundamental questions.

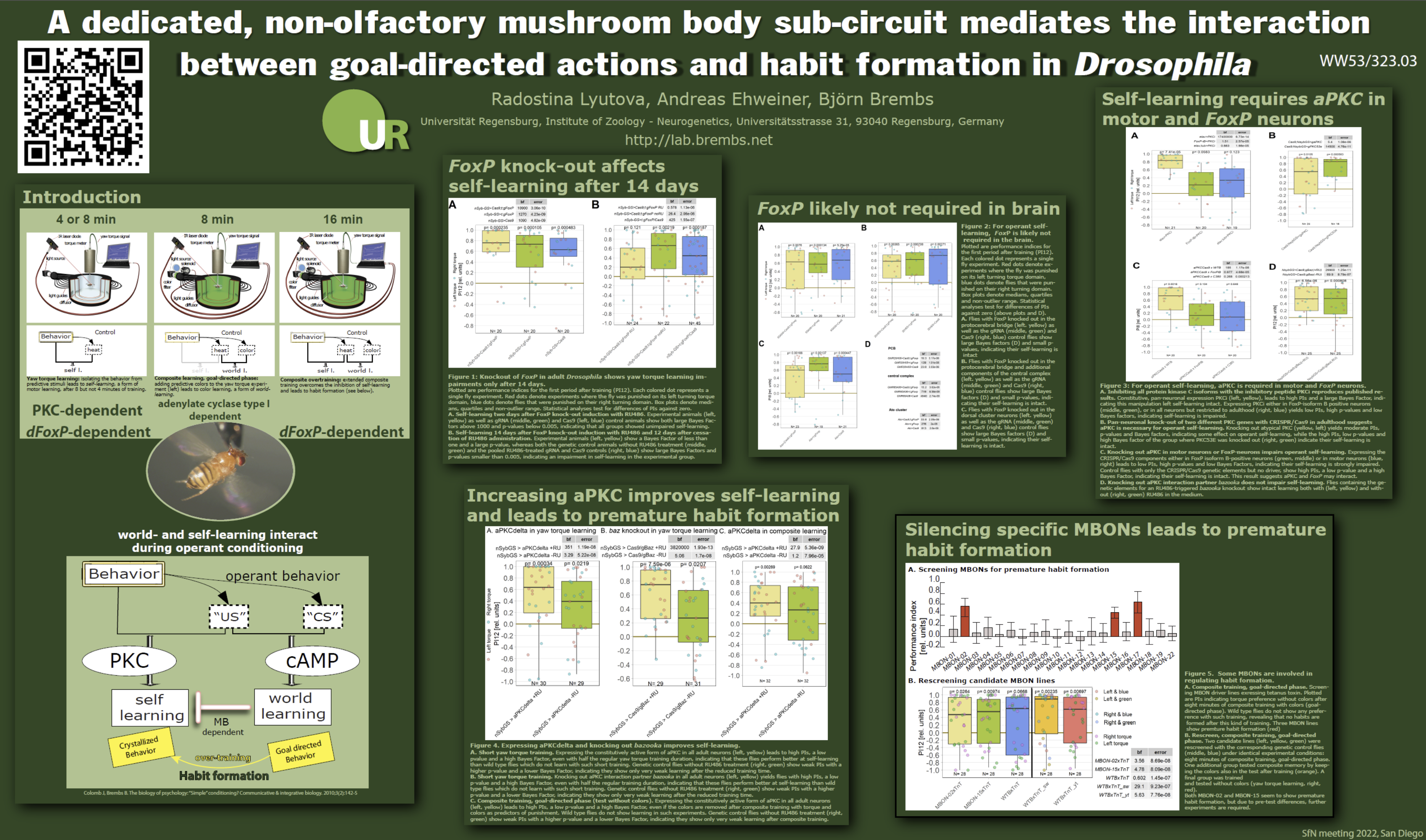

The first major breakthrough from my perspective came with our discovery that operant and classical processes can be genetically separated, using the right behavioral experiments. The experimental separation of ‘Skinnerian’ and ‘Pavlovian’ components had not been possible before. These results showed that what made these processes different was not how the animal was learning (i.e., operantly or classically), but what it learned (i.e., about external stimuli, e.g. Pavlov’s bell, or about their own behavior, e.g. pressing the lever in a Skinner box). Thus, in order to avoid confusion between the procedures (operant vs. classical) and the mechanisms, we had to come up with descriptive terms for the learning mechanisms. After much discussion and back-and-forth, we arrived at ‘world-learning’ for the mechanism that detects and processes relationships in the external world and at ‘self-learning’ for the mechanism that detects and processes the consequences of an animal’s own behavior.

The main reason why traditional experiments failed to uncover this distinction appears to be that the depressed lever in a Skinner box constitutes an external stimulus that signals food for the animal, just as Pavlov’s bell does for his dogs. Much like Pavlov’s dogs would bark at the bell when hungry, rats in a Skinner box use whatever means they have to press the lever – the specific behavior for pressing the lever is not relevant and hence not learned. Skinner himself noted that “The lever cannot be removed” as a technical problem in studying the processes involved in his type of conditioning. In our experiments, we were able to overcome this problem and find the genetically separable mechanisms, which later were shown by other groups to be evolutionarily conserved.

We have since found out that the two learning mechanisms interact in order to establish adaptive behavioral choice and allow the animal to always establish the right equilibrium between efficiency and flexibility while it is balancing the need to explore new resources with the need to exploit the resource at hand.

Now, after all these years, it is the greatest honor to be invited to give the keynote address to an entire session just on this research topic. Granted, this is not a major conference with thousands of attendees – it is a small meeting with only a few dozen people. Nevertheless, after almost two generations of researchers came and went, these people are the remaining experts for a field long abandoned by many colleagues as an unsolvable problem. If you find this long-standing and challenging research topic as exciting as we do, I invite you to join us in Winter Park, Colorado this coming February 8-12, 2014.

Information from the organizer:

The Winter Conference on Animal Learning and Behavior will convene in Winter Park, Colorado from Saturday evening, February 8, with departure Wednesday morning, February 12, 2014. If you are interested in attending WCALB 2014, please send your small refundable deposit by October 21, 2013 so we know how many condominiums to reserve. See “*DEPOSITS*” section below.

*KEYNOTE ADDRESS*

“Pavlovian and Skinnerian Processes are Genetically Separable”

Björn Brembs, Universität Regensburg

Abstract–The commonalities and differences between operant and classical conditioning have been debated ever since Skinner and Konorski embarked on their epic exchange about “two types of conditioned reflex and a pseudo type” in the 1930s. New techniques that surmount experimental design problems identified in early research allow for a much improved separation of the two types of conditioning. These technical advances, combined with modern genetic manipulations, provide evidence that Pavlovian and Skinnerian processes separate not between the learning procedure (operant vs. classical), but between learning content (self vs. non-self). The picture emerging today reinforces Skinner’s early insight that operant conditioning is a composite situation, comprised of a ‘Pavlovian’ component (learning about stimuli – ‘world-learning’) and a ‘Skinnerian’ component (learning about the consequences of actions – ‘self-learning’). A research program that distinguished these processes genetically is described.

Björn Brembs is Professor of Neurogenetics at Universität Regensburg. He obtained his doctorate in genetics and neurobiology from Universität Würzburg and has done post-doctoral research at the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center.Thematically, Dr. Brembs’ research concerns the general organization of behavior with regards to reward and punishment with the objective of better understanding how brains accomplish adaptive behavioral choice.

*FOCUS SESSION*

“Operant and Classical Learning: Comparisons and Interactions”

Allen Neuringer, Peter Killeen, Jeremie Jozefowiez (Université Lille Nord de France), Michael Commons, Karen Pryor and Stanley Weiss have already joined the Focus Session. The format is presentations (up to 25-minutes) with extended discussion among participants in a Research Seminar Session. Additional qualified participants can be added. Let me (sweiss@american.edu) know if you would like to join this session.

*MEETING, WINTER PARK AND ACCOMMODATIONS*

The Winter Conference is a friendly and informal meeting that provides an opportunity to combine intensive, scientifically rigorous discussions — related to animal conditioning, behavior and learning — with skiing at one of Colorado’s premier ski areas, Winter Park. See website (https://www.american.edu/cas/psychology/wcalb/index.cfm) for breadth of WCALB paper sessions that reflect participants’ research interests. All participants are invited to make a presentation and suggest topics. Graduate students are welcome and can present with their advisor’s endorsement.

There is downhill skiing for all skill levels, up to black diamond, as well as excellent cross-country skiing in the Arapaho National Forest, Devil’s Thumb and Snow Mountain Ranch. The majestic snow-covered Rockies in winter are breathtaking.

The all inclusive cost for registration, four days in a shared Snowblaze condominium, an opening buffet reception and dinner at a fine Winter Park restaurant is only $375/person or $750/couple (couples have their own room, usually with private bath, in a condo). The Snowblaze is located in Winter Park near restaurants and shops. It has an excellent health club with sauna, steam room, hot tub, pool, weight room and handball courts. All units have complete kitchens.

If available, a family can have an entire 2-bedroom condominium unit for $1,125 plus $115 for each person over three. The 2-bedroom units each sleep up to six people if a convertible sofa in the living room is used. All family members are invited to the opening buffet reception, Conference dinner and sessions.

*DEPOSITS*

We will be in the Colorado Rockies just a week before the prime ski season starts. Therefore, condominiums must be reserved early. If you think you would like to attend WCALB 2014, please let me (sweiss@american.edu) know ASAP by e-mail and send your *refundable* (until November 30) deposit ($50 per person, $100 per couple, $200 per family) by October 21, 2013. This will help insure a place for you in our limited number of reserved condominiums. Make checks out to Stanley Weiss, WCALB with “WCALB 2014″ in the lower left corner. Final payment is due November 30, 2013.

Please send your payment to:

Stanley Weiss, Convener

Winter Conference on Animal Learning & Behavior

Department of Psychology

AmericanUniversity

Washington, DC 20016

We will do our best to include late registrants in the Conference, but often they have had to pay substantially more for their accommodations because our reserved condominiums were full.Therefore, if you are interested in attending the Conference let me know soon and send your refundable (until November 30) deposit. A CALL for presentations will go out to registered participants in early December.If you have any questions or suggestions, contact me at sweiss@american.edu.

I hope to see you in Winter Park!

Stan

Stanley J. Weiss

Professor of Experimental Psychology Emeritus

American University

Washington, D. C. 20016

Phone: 301-656-3454

Fax: 202-885-1023

e-mail:sweiss@american.edu

B. F. Skinner (1935). Two Types of Conditioned Reflex and a Pseudo Type The Journal of General Psychology, 12 (1), 66-77 DOI: 10.1080/00221309.1935.9920088

J. Konorski, & S. Miller (1937). On Two Types of Conditioned Reflex The Journal of General Psychology, 16 (1), 264-272 DOI: 10.1080/00221309.1937.9917950

B. F. Skinner (1937). Two Types of Conditioned Reflex: A Reply to Konorski and Miller The Journal of General Psychology, 16 (1), 272-279 DOI: 10.1080/00221309.1937.9917951

J. Konorski, & S. Miller (1937). Further Remarks on two Types of Conditioned Reflex The Journal of General Psychology, 17 (1), 405-407 DOI: 10.1080/00221309.1937.9918010

The difference between ‘how and what animals and beings in general learn’ and behave is important. When learning how to do something both the central and peripheral nervous systems are being used. Learning not to touch something because its hot or dangerous is the specific somatic system relying every touch to the brain. ‘two learning mechanisms working hand in hand with each other’ is an example of synaptic vesicles and the receptor sites. If the receptor site sand the vesicle don’t fit together exactly then they won’t work which causes problems. Just like you can’t use one learning mechanism without the other. Many things go hand and hand, without one then the other wouldn’t function properly.

The findings for classical and operant conditioning from B.F. Skinner and Ivan Pavlov are very significant to the learning portion of psychology. Operant conditioning works with associating cognitive behaviors and consequences, such as studying hard to make the dean’s list, resulting in the effect of whether or not you will study again in the future. Classical conditioning works with learned behaviors, such as ringing a bell to get a dog to salivate and expect his meal. The major difference between the two is how the behavior is learned. Classical conditioning uses stimuli paired with response mechanisms, while operant conditioning uses reinforcement, punishment and shaping. Mechanisms within our brains must work together in order for us to learn new behaviors. If one portion of the brain is not functioning correctly, it becomes harder to learn certain behaviors and become conditioned-whether it be classical or operant. The term “world-learning” is an excellent way to describe Pavlov’s ideas of classical conditioning, and “self-learning” best describes Skinner’s ideas of operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are essentially the same thing. It’s just that with the classical conditioning, you’re working more so with learned behaviors and trying to get the same kind of response. Where as with operant conditioning, it’s more about consequences and manipulating responses with shaping and punishment.

You write: “Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are essentially the same thing.”

As I wrote in the post, this is both correct and wrong.

If there are predictive stimuli in the operant experiment, then the animal learns about those stimuli and the difference to classical conditioning, where the animal also learns about two stimuli, is minimal.

However, if you isolate the self-learning component in operant conditioning, then classical conditioning engages the canonical cAMP cascade and is not PKC-dependent whereas the self-learning mechanism in operant conditioning depends on PKC and not on the canonical cAMP pathway. They couldn’t possibly be any more different than this double dissociation.

Classical and Operant conditioning vary in many ways, but also have their similarities. We use classical conditioning to get an organism to show us a response to our stimulus. Just as in Pavlov’s experiment. Pavlov uses the neutral stimulus( the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus( the food), which triggers the unconditioned response of salivation in the dogs mouth. When using the neutral stimulus and unconditioned stimulus together it showed the dog the correlation between him receiving the food at the ring of the bell, which sparked the conditioned stimulus( the Bell) and then the Conditioned reflex the dog salivation. Operant conditioning on the other hand was founded by skinner and is generally is used with reinforcement and punishment. Such as if you were about to give a speech for speech class. You practice and practice and practice and then get an A+ on your speech from doing so well. Here you have received positive reinforcement and now are more likely to practice for your next speech to receive the same reinforcement. Both Operant and Classical conditioning are used to alter behaviors in certain situations.

The two different methods of learning are somewhat similar, but do have their differences. The introduction of classical conditioning was brought upon by the Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov noticed that every time a bell rang, the dogs mouth would salivate. The natural stimulus of this experiment would be the bell. The dog salivating is an example of an unconditioned response. The food is the unconditioned stimulus. Therefore, classical conditioning deals with the behaviors that are elicited automatically by stimulus. On the other hand, Operate conditioning brings a different approach to the table. B.F. Skinner coined the term operate in 1953 to describe any behavior that in involves consequence. Their can also can positive and negative reinforcements that act as a key tool in operate conditioning. So, with the introduction of operate condition you could describe as the process in which your behavior and actions are shaped and maintained by the consequences you receive. As you can see, Classical and Operate conditioning are similar but also contain differences.

Dear Megan and Tony, many thanks for commenting. The commonalities and differences between operant and classical conditioning you point out are, of course, correct. This is precisely what Skinner and Pavlov’s students discussed in the 1930s as you can see in th references I provided. However, our research shows that these procedural differences are entirely irrelevant to the processes that go on in the animal’s brain. What matters is what the animals learn (self- vs. world-learning) not how they learn it (operantly vs. classically). This is precisely the advance we contributed to the debate, as the points you emphasize were already known in 1935. As I wrote in the post: “These results showed that what made these processes different was not how the animal was learning (i.e., operantly or classically), but what it learned (i.e., about external stimuli, e.g. Pavlov’s bell, or about their own behavior, e.g. pressing the lever in a Skinner box). ”

Thus, while what you describe is correct, it also turned out to be quite irrelevant in some ways, to the whole problem.