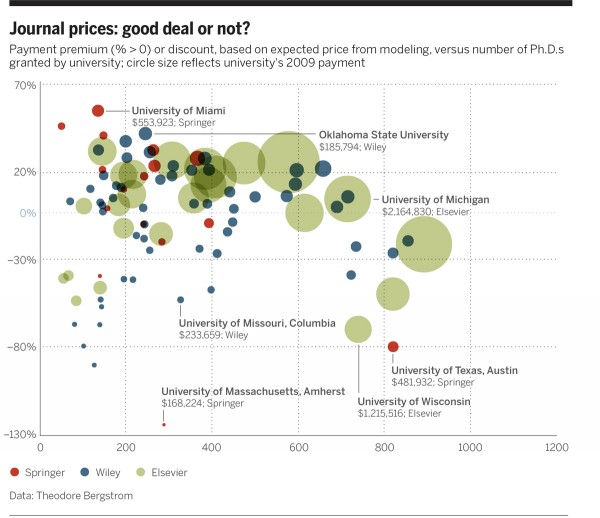

There is an interesting study out in the journal PNAS: “Evaluating big deal journal bundles“. The study details the disparity in negotiation skills between different US institutions when haggling with publishers about subscription pricing. For Science Magazine, John Bohannon of “journal sting” fame, wrote a news article about the study, which did not really help him gain any respect back from all that he lost with his ill-fated sting-piece. While the study itself focused on journal pricing among US-based institutions, Bohannon’s news article, where one would expect a little broader perspective than in the commonly more myopic original papers, fails to mention that even the ‘best’ big deals are grossly overcharging the taxpayer. Here is the figure of the article, apparently provided by the PNAS authors:

This graph shows that some universities pay more for subscriptions than others. I’m not sure what exactly -130% is supposed to mean. I take it that UMass didn’t receive money from Springer, but still paid $168,224. So I take this graph to mean that there are differences of up to 200% between what libraries are paying publishers, i.e, one university may pay up to 200% on top of what another library is paying for the same content, e.g. when one pays one million, another has to pay three. I’m not entirely sure that this is the correct reading of the Y-axis, but it’s the best I can do for now.

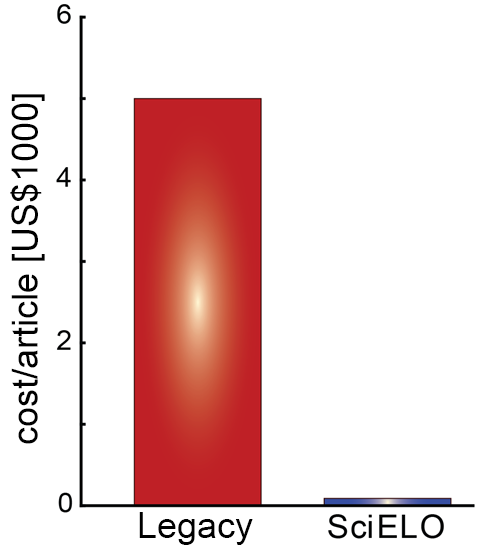

Being charged 200% more than other libraries for the same service may hurt, but consider what we would be paying if we wouldn’t use publishers, but instead published all our papers in a system like SciELO:

According to a Nature article citing Outsell, we currently pay US$5,000 per article to prevent public access to it, while the overall cost of a publicly accessible article in SciELO is only US$90. Try to explain that to a taxpayer on the street: you pay $5,000 for each article you’re not allowed to read, instead of just $90 for each article you could read. In the light of such numbers, it is a sign of a truly warped perspective when people can still discuss a few percentage points more or less for what they pay to block public access to research. Because this is what libraries do by paying subscription fees: they pay to block public access to research.

Be that as it may, if I were to calculate any percentages from these differences, I could say that subscriptions are in excess of 5000% more expensive than SciELO or that SciELO would only cost institutions 1.8% of what they are currently paying for the same service, or that we are overpaying legacy publishers by 98.2%. So either way you see it, we could pay less than 2% of the current cost or are currently paying more than 5000% too much – compared to these figures, the 200% seems like a totally negligible number to me. In the words of Science Magazine: no matter what your university paid for subscriptions, they definitely got a horrible deal – even if it was the best deal in the country.

Nevertheless, given the effective distraction machine that Science Magazine is turning into, I expect people will discuss the irrelevant 200% much more extensively, than the crucial 1.8% or 5000%.

What we should instead discuss is the following:

Why are we paying to block public access to research, when we could save billions by allowing access?

For those who can’t access the PNAS paper, a copy is archived at figshare https://figshare.com/articles/Evaluating_big_deal_journal_bundles/1059179

Not only saving billions but ADDITIONALLY getting extra value from easier & wider access to research literature. Quantifying that later element economically is difficult but it’s real & often overlooked. It’s not *just* that we’d save billions, we’d also get additional benefit/innovation that simply isn’t possible within the paywall system!

Just as soon as the academics who insist we need these journals to assess themselves and each other change their minds and let libraries cancel them the problem will be solved. Libraries don’t buy journals for librarians. We buy them because academics insist we do.

I did not look at the study, but it seems that the percentages are deviations from the expected prices derived from a model estimated in the article (line above the figure).

So -130% of the expected price means that Springer paid UMass 30% of the price UMass was expected to pay? 🙂 I want to go shopping in stores where I pay 130% less than what I would be expected to pay! 🙂