Over the last ten years, scientific funding agencies across the globe have implemented policies which force their grant recipients to behave in a compliant way. For instance, the NIH OA policy mandates that research articles describing research they funded must be available via PubMedCentral within 12 months of publication. Other funders and also some institutions have implemented various policies with similar mandates.

In principle, such mandates are great not only because they demonstrate the intention of the mandating organization to put the interest of the public over the interest of authors and publishers. They also can be quite effective, to some extent, as the NIH mandate or the one from the University of Liège.

At the same time, such individual mandates are suboptimal for a variety of reasons, e.g.:

- In general, mandates are evidence that the system is not working as intended. After all, mandates intend to force people to behave in a way they otherwise would not behave. Mandates are thus no more than stop-gap measures for a badly designed system, instead of measures designed to eliminate the underlying systemic reasons for the undesired behavior.

- Funder mandates also seem to be designed to counter-act unintended consequences of competitive grant awards: competitive behavior. To be awarded research grants, what counts are publications, both many and in the right journals. So researchers will make sure no competitor gets any inside information too early and will try to close off as much of their research for as long as possible, including text, data and code. Mandates are designed to counter-act this competitive behavior, which means that on the one hand, funders incentivize one behavior and on the other punish it with a mandate. This is not what one would call clever design.

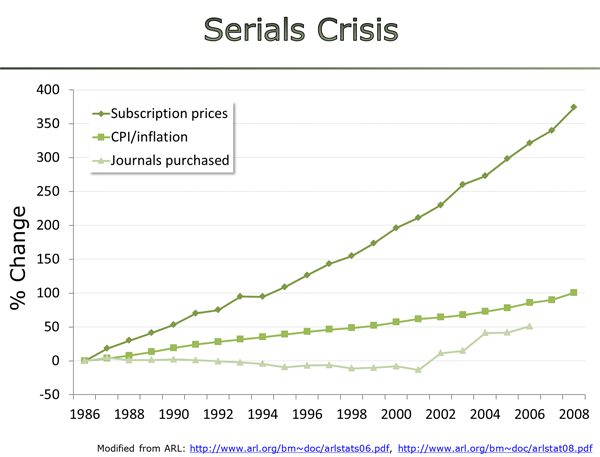

- Depending on the range of the behaviors intended to control, mandates are also notoriously difficult and tedious to monitor and enforce. For instance, if the mandate concerns depositing a copy of a publication in a repository, manual checks would have to be performed for each grant recipient. This is the reason the NIH have introduced automatic deposition in PMC. If re-use licenses are mandated, they also need to be tested for compliance. If only certain types of journals qualify for compliance, the 30k journals need to be vetted – or at least those where grant recipients have published. Caps on article processing charges (APCs) are essentially impossible to enforce, as no funder has jurisdiction over what private companies can ask for their products, nor the possibility to legally monitor the bank accounts of grant recipients for possible payments above mandated spending caps. Here in Germany, our funder, the DFG has had an APC cap in place for more than 10 years now and grant recipients simply pay any amount exceeding the cap from other sources.

- In countries such as Germany, where academic freedom is written into the constitution, such individual mandates are considered an infringement on this basic right. There currently is a law suit in Germany, brought by several law professors against their university for mandating a deposit of a copy of all articles in the university’s repository. In such countries, the mandate solution is highly likely to fail.

- Mandates, as the name implies, is a form of coercion to force people to behave in ways they would not otherwise behave. Besides the bureaucratic efforts needed to monitor and enforce compliance, mandates are bound to be met with resistance by those coerced by the mandate to perform additional work that takes time away from work seen as more pressing or important. There may thus be resistance both to the implementation and the enforcement of mandates that appear to be too coercive, reducing the effectiveness of the mandates.

For about the same time as the individual mandates, if not for longer, funders have also provided guidelines for the kind of infrastructure the institutions should provide grant recipients with. In contrast to individual mandates, these guidelines have not been enforced at all. For instance, the DFG endorses the European Charter for Access to Research Infrastructures and suggests (in more than just one document) that institutions provide DFG grant recipients with research infrastructure that includes, e.g., data repositories for access and long-term archiving. To my knowledge, such repositories are far from standard at German institutions. In addition, the DFG is part of an ongoing, nation-wide initiative to strengthen digital infrastructures for text, data and code. As an example, within this initiative, we have created guidelines for how research institutions should support the creation and use of scientific code and software. However, to this day, there is no mechanism in place to certify compliance of the funded institutions with these documents.

In the light of these aspects, would it not be wise to enforce these guidelines to an extent that using these research infrastructures would save researchers effort and make them compliant with the individual mandates at the same time? In other words, could the funders not save a lot of time and energy by enforcing institutions to provide research infrastructure that enables their grant recipients to effortlessly become compliant with individual mandates? In fact, such institutional ‘mandates’ would make the desired behavior also the most time and effort saving behavior, perhaps making individual mandates redundant?

Instead of monitoring individual grant recipients or journals or articles, funders would only have to implement, e.g., a certification procedure. Only applications from certified institutions would qualify for research grants. Such strict requirements are rather commonplace as, e.g., in many countries only accredited institutions qualify. Moreover, on top of such general requirements, there can be very specific infrastructure requirements for certain projects, such as a core facility for certain high-throughput experiments. In this case, the specifications can even extend to certain research and technical staff and whether or not the core facility needs permanent staffing or temporary positions. Thus, it seems, such a certification procedure would be a rather small step for funders already set up to monitor institutions for their infrastructure capabilities.

If groups of funders, such as cOAlition S, coordinated their technical requirements as they have been coordinating their individual mandates, the resulting infrastructure requirements would include FAIR principles, which would lead to a decentralized, interoperable infrastructure. under the governance of the scientific community. As this infrastructure is intended to replace current subscription publishing with a platform that integrates our text-based narratives with our data and code, it would be straightforward for the funders to suggest that an obvious source of funds for the required infrastructure would be subscriptions. As most scholarly articles are available without subscriptions anyway and implementing the infrastructure is much cheaper, on average, than subscriptions, the implementation should be possible without disruption and with considerable cost reductions for the institutions. If an institution considers their library to be the traditional place where the output of scholars is curated, made accessible and archived, then there would not even have to be a redirection of funds from library subscriptions to different infrastructure units – the money would stay within the libraries. But of course, institutions would in principle remain free to source the funds any way they see fit.

Libraries themselves would not only see a massive upgrade as they would now be one of the most central infrastructure units within each institute, they would also rid themselves of the loathsome negotiations with the parasitic publishers, a task, librarians tell me, which no librarian loves. Through their media expertise and their experience with direct user contact libraries would also be ideally placed to handle the implementation of the infrastructure and training users.

Faculty would then enjoy never to have to worry about their data or their code ever again, as their institutions would now have an infrastructure that automatically takes care of these outputs. Inasmuch as institutions were to cancel subscriptions, there also would be no free/paid alternative to publish than the infrastructure provided by the institutions, as the cash-strapped publishers would have to close down their journals. Moreover, the integration of authoring systems with scientific data and code makes drafting manuscripts much easier and publication/submission is just a single click, such that any faculty who values their time will use this system simply because it is superior to the antiquated way we publish today. Faculty as readers will also use this system as it comes with a modern, customizable sort, filter and discovery system, vastly surpassing any filtering the ancient journals could ever accomplish.

Taken together, such a certification process would only be a small step for funders already inclined to push harder to make the research they funded accessible, save institutions a lot of money every year, be welcomed by libraries and a time saver for faculty, who would not have to be forced to use this conveniently invisible infrastructure.

Open standards underlying the infrastructure ensure a lively market of service providers, as the standards make the services truly substitutable: if an institution is not satisfied with the service of company A, it can choose company B for the next contract, ensuring sufficient competition to keep prices down permanently. For this reason, objections to such a certification process can only come from one group of stakeholders: the legacy publishers who, faced with actual competition, will not be able to enjoy their huge profit margins any longer, while all other stakeholders enjoy their much improved situation all around.

Like this:

Like Loading...