In his fantastic Peters Memorial Lecture on occasion of receiving CNI‘s Paul Evan Peters award, Herbert Van de Sompel of Los Alamos National Laboratory described my calls to drop subscriptions as “radical” and “extremist” (starting at about minute 58):

Regardless of what Herbert called my views, this is a must-see presentation in which Herbert essentially presents the technology and standards behind the functionalities I have been asking for and have been trying to get implemented for the last decade or so. Apparently, where we differ is only that I actually want to use the functionalities and concepts he describes in his presentation and, consequently, I am naive or idealistic enough to think of ways to get there. If this makes me a radical, so be it: radix is Latin for ‘root’ and I try to tackle the root of our problems.

Right before he talks about me, he also mentions David Lewis’ 2.5% Commitment, which I also support. In Cameron Neylon’s critique of Lewis’ approach one can find an important realization that bears quoting and repeating as it is one of the main obstacles why Herbert thinks we will never have the tools he describes in his presentation. Cameron writes:

That in turn is the problem in the scholarly communication space. Such shared identities and notions of consent do not exist. The somewhat unproductive argument over whether it is the libraries responsibility to cut subscriptions or academics responsibility to ask them to illustrates this. It is actually a shared responsibility, but one that is not supported by sense of shared identity and purpose, certainly not of shared governance. And notably success stories in cutting subscriptions all feature serious efforts to form and strengthen shared identity and purpose within an institution before taking action.

Cameron very astutely dissects one of the main sociological issues holding us back: scholars do not share a common identity any more, just as librarians and faculty do not and just as different scholarly institutions do not share an identity with each other. So pernicious an effect have the neoliberal mantras of “competition” and “every man for himself” had on scholarship, that it has all but completely disintegrated into either warring factions or competing careerists. University rankings provide a clear metaphor for scholarly institutions as players in a competition for whatever the neoliberal ideologues want them to compete for: funds, human resources or prestige (aka. the scholarly fetish “excellence“). If you talk to current university presidents, deans or provosts or read what they have written, it seems as if most of them have completely absorbed the neoliberal cool-aid and made themselves the defenders of individuality, competition and external ‘incentives’, with the underlying assumption that without those concepts, everybody in academia would just sit in their comfy chairs and collect tax funds, twiddling their thumbs. Apparently, carrots and sticks are the only way to squeeze excellence out of otherwise lazy, selfish and parasitic scholars. Ironically, election data suggest that a large section of these scholarly politicians, if they are representative of their academic peers at large, may go on to vote for left-of-center parties or candidates who vow to combat exactly the neoliberal policies they so ardently defend in their day jobs.

Be that as it may, apparently even for an advocate and expert like Herbert, asking scholars to cooperate in order to achieve a greater, public good, has now become sufficient grounds to label someone who strives for cooperation as a “radical” or an “extremist”. If indeed he is correct and in 2018 asking scholars to behave cooperatively, rather than competitively, is something so exotic and outrageous, scholarship has deserved the state it currently is in.

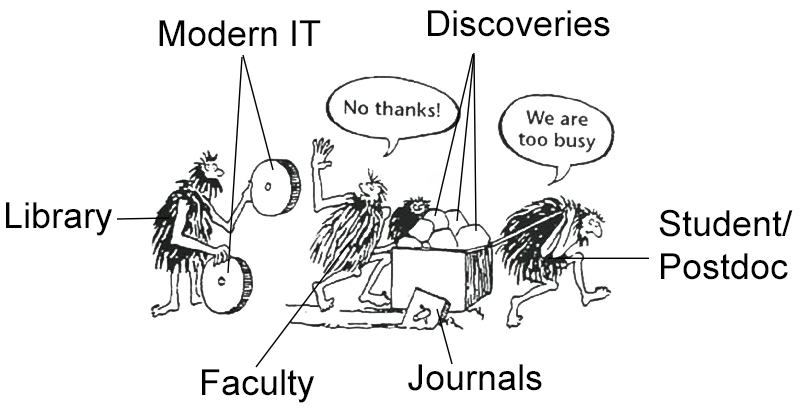

These thoughts have reminded me of an old cartoon I’ve been showing in many of my presentations. Now, I’m posting a disambiguated version of the cartoon (sorry, I can’t provide a source for the cartoon, created it from a photograph I once was sent) that I hope explains in an entertaining way why dropping all subscriptions and buying Herbert’s solutions from the money instead isn’t extreme at all (click for larger image):

All scholars and those working to support scholars share a common identity. Cameron is spot on in that all too few are realizing that we all strive for better scholarship, for more knowledge. Acquiring knowledge for its own sake is one of the very few behaviors that humans do not share with other animals and all scholars share a particular enthusiasm for knowledge. In fact, the German word for scholarship is “Wissenschaft”, literally translated with “knowledge creation”. In this argument, it doesn’t matter if scholar A is at institution X and librarian B is at institution Y – they are all scholars.

All scholars and those working to support scholars share a common identity. Cameron is spot on in that all too few are realizing that we all strive for better scholarship, for more knowledge. Acquiring knowledge for its own sake is one of the very few behaviors that humans do not share with other animals and all scholars share a particular enthusiasm for knowledge. In fact, the German word for scholarship is “Wissenschaft”, literally translated with “knowledge creation”. In this argument, it doesn’t matter if scholar A is at institution X and librarian B is at institution Y – they are all scholars.

I must assume (not having been there) that this sense of communalism (to use Merton’s term) and shared identity (to use Cameron’s term) must have been much more prevalent in the early 1990s when institutions invested in routers, cables, computers and other hardware (and time!) for something that nobody knew what it could do: the WWW. I often wonder what faculty would have said around 1992 (first time I had an email address), when asked by a computing center employee: “wouldn’t you like a new service, let’s call it ’email’ by which your students could reach you 24/7?”. I would tend to believe that if that had been the mindset of infrastructure experts at the time, we would not have any internet today.

Instead, infrastructure experts at the time embraced the new technology, were competent enough to realize which standards worked and would be sustainable long into the future and started spending some serious money – regardless of whether faculty expressed any interest in using any of this technology. In contrast, today, we stand to save money from adopting the standards Herbert talks about and yet thinking about how to practically achieve adoption of such common standards is grounds for being labeled an extremist. How dare I suggest implementing modern technology without asking faculty first! Today, we have similarly competent experts like Herbert, but they seem to despair, expecting this modern technology to never arrive for scholarship, instead of doing what their predecessors have done: embrace the new technology and the potential it brings and implement it. What a difference 25 years make: the common good was sufficient cause for spending money in the 1990s, when today it is seen as ‘extremist’ just to try and save money while promoting the common good.

Today, librarians and other infrastructure experts dare not implement modern technology without fear of reprisals: after all, faculty are not colleagues any more who share a common identity, they are customers and librarians are service providers in this corporation only called ‘university’ for dusty historical reasons. Clearly, single institutions cannot act without risking league table standings or the competitiveness of their labor force. Everyone is busy chasing prestige in an absurd artificial competition where “excellence” is the only thing that counts, but can’t itself be counted. Some of Monty Python’s most absurd sketches appear rational in comparison.

When done competently, dropping subscriptions today doesn’t risk anybody’s livelihoods or league standings any more. Thanks to a growing set of tools, journals remain accessible during the transition period. The old adage “everybody who needs access has access”, once used to resist open access campaigning, has finally become true – without subscriptions. We just need to take advantage of the new circumstances. After the transition, nobody needs access to journals that do not exist any more, so the enabling properties of this toolset are decisive here and the set not comprising a solution becomes irrelevant: we have the solutions, as Herbert so eloquently explains. What we need are enabling technologies. We have those now, too. Most journals won’t survive being cut off from all funding.

And yet, faculty continue to chase journal spots as vehicles for their discoveries from which they hope to harvest sufficient prestige just to keep going. Without removing this source of prestige, faculty and students/postdocs have little other choice than to reject the better vehicles we now could offer. This is the main reason why 25 years of campaigning for scholarly infrastructure reform have barely brought scholarship to embrace the web of 1995 (in the words of Jon Tennant). Journals, the square wheels, are the main physical obstacles to the technology Herbert describes in his presentation. They need to go. That is a rational solution that targets the root of the problem. If scholars can find the Higgs Boson, I’m confident they can find other sources of prestige once journals have ceased to exist – should they decide that chasing prestige is a functionality they wish to replicate.

Coincidentally, journal subscriptions also usurp most of the funds required for implementing Herbert’s solutions – the round wheels. Canceling subscriptions hence serves two main purposes: removing the main obstacle for scholars using modern information technology and freeing up funds to implement said technology: removing the square wheels and replacing them with round wheels. Subscription journals are the keystone in the current scholarly communication arch: remove them and it all falls apart. Any journal-like functionality that scholars value is easily recreated with modern technology, but with new functionalities and few, if any, of the current disadvantages and unintended consequences.

Finally, with scholars so busy chasing excellence, chances are slim to none they will ever ask for round wheels, as so many librarians I speak to seem to hope for.

It will be hard to get rid of the commercial publishers. I am exploring something that will hopefully make the transition easier: grassroots scientific publishing. Where a scientific community curates the articles in their field, in that way bring all articles scattered over many journals together, explain which ones are important and why. And stays up to date.

https://grassrootspublishing.wordpress.com/

It starts by doing this better kind of review for already published articles/preprints, but once accepted as a good way of quality assurance, we could do the same for manuscripts and would not longer need publishers. To show how it would work I have started a journal for my own field of study:

https://homogenisation.wordpress.com/

Thank you for your comment. Exciting initiative! Indeed, any wordpress-hosted article has more digital functionality than any legacy article.

There are two details I’d like to know your answer to:

1. You wrote “it will be hard to get rid of commercial publishers”. How would commercial publishers survive without cash flow?

2. What is your strategy to convince about 7 million authors (full time equivalents, according to the UN) to risk their careers and what is your time-estimate for reaching that goal?

To start with question 2. No idea why you are asking me. My plan is for scientific communities to assess published articles as well. Authors thus do not have to risk their careers. Once the system is accepted, it will not be a risk any more to ignore the publishers.

That may be the key idea, authors do not have to submit their articles to new unproven journals. The grassroots journals will simply assess all articles and manuscripts they can find. That is how we can escape the vicious circle.

Question 2 would be my question to you, Björn. I do not think just appealing to higher motives will convince about 7 million authors to risk their careers. Without breaking the vicious cycle question 1 is thus superfluous, the monopolistic profits will keep on being handed to the publishers.

Publishing is no longer hard, ArXiv does it for 1$ per manuscript, all the publishers have is their brand names. Thus we have to create a new quality assurance system. If we make a better one, 7 million authors will be happy and the publishers are dead.

How fast it will go will depend on how much support the idea will find. I naturally like it, but we will have to see what the world will say.

Sorry, I may be misunderstanding something. I thought you were providing an opportunity for creating community journals, maybe that’s not all of your plan? Clearly, if I had a paper that could get published in Nature or Science and I chose instead to publish it in a community journal on WordPress, I clearly would be risking my career (depending on the filed of study, of course). Hence, any reform that is based on authors choosing to not publish in a GlamMag is simultaneously based on authors risking their careers. This is what Stevan Harnad suggested 25 years ago in his “Subversive Proposal” and which in the last 25 years has not happened.

In terms of assessing already published articles, we already have, e.g., PubPeer and it certainly has not changed authors’ publishing behavior one bit.

Taken together, I think there is plenty of historical evidence that neither new publishing venues, nor post-publication review has changed authors’ behavior at all. Thus, I’m not sure repeating previously failed strategies is a smart move. Again, I may have misunderstood the solutions you propose. In this case I apologize and would ask for a clarification.

For the cash flow via subscriptions to end, you do not need 7 million authors to risk their careers, that’s my whole point. We have to convince a few thousand infrastructure experts in the world’s libraries and computing centers to simply do their job: shift funds away from subscriptions (which are a waste of money) towards a sustainable infrastructure, as, e.g., described here:

https://bjoern.brembs.net/2015/04/what-should-a-modern-scientific-infrastructure-look-like/

Clearly, all librarians I talked to see the advantages of a modern IT system over 17th century subscriptions. Hence, if they just did their job of providing us with the best infrastructure money can buy, subscriptions would not even be on the list of things to buy. Obviously, convincing a few thousand to do their job should be easier than to convince a few million to risk their job. Which is why I propose to direct all our campaigning efforts not to researchers but to librarians. The message of the campaign should simply be: get us the best infrastructure for our money. Arguably, that’s at least a new approach and not a repetition of a failed approach. I’m not sure that it will work, but at least it’s not a failed approach.

Everybody already knows that the journals do not provide a quality assurance system:

https://bjoern.brembs.net/2013/06/everybody-already-knows-journal-rank-is-bunk/

and still, this insight hasn’t changed authors’ behavior, neither has PubPeer. I would take that as evidence that just providing a better quality control system will have zero effect in the future just as it has had zero effect in the past. Even if Nature or Science were widely known that they publish the worst science (which they in fact do), people will still publish there, if they think their livelihoods depend on it.

Thus, it seems there is sufficient evidence that additional publishing or quality control options have failed in the past. I’m not sure just trying the same failed strategies over and over again is a worthwhile effort. I’d rather try something new.

Comments are closed.