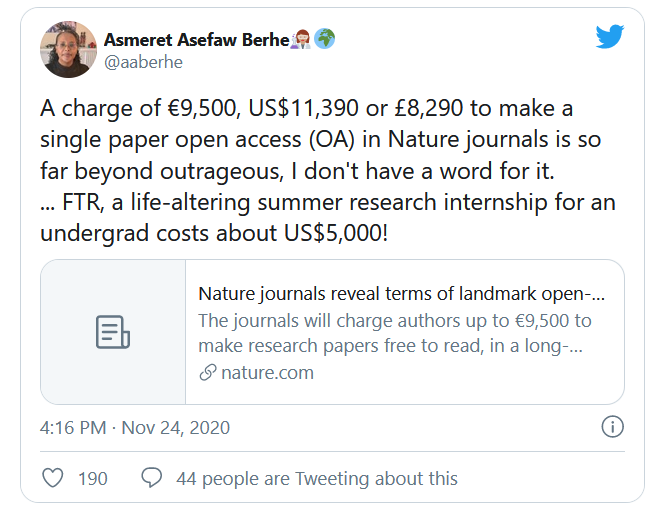

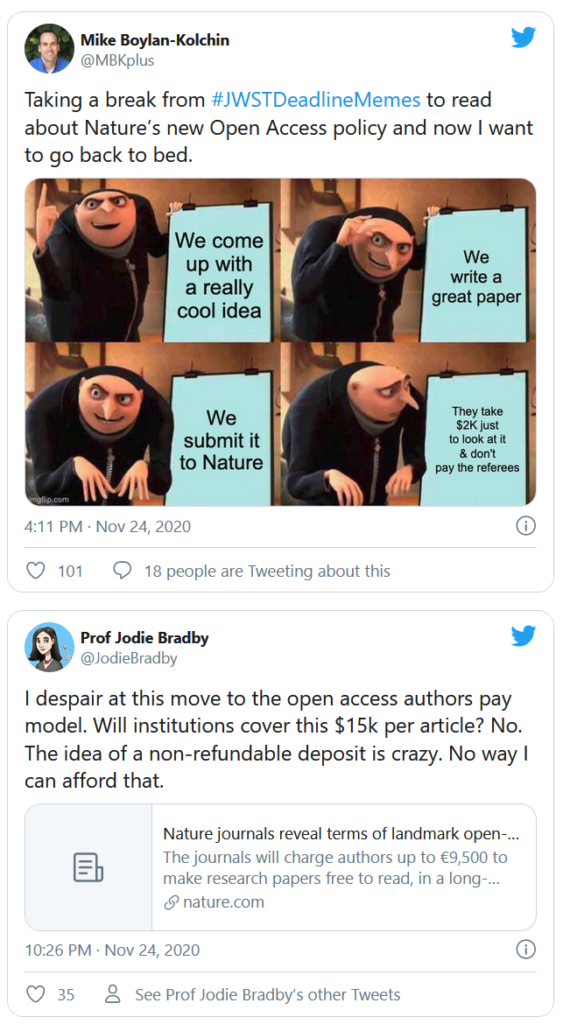

There has been some outrage at the announcement that Nature is following through with their 2004 declaration of charging ~10k ($/€) in article processing charges (APCs). However, not only have these charges been 16 years in the making but the original declaration was made not on some obscure blog, but at a UK parliamentary inquiry. So nobody could rightfully claim that we couldn’t have seen this development coming from miles away.

In fact, already more than 10 years ago, such high APCs were very much welcomed, as people thought they could bring about change in scholarly publishing. Some examples, starting with Peter Suber in 2009:

As soon as we shift costs from the reader side to the author side, then, we create market pressure to keep them low enough to attract rather than deter authors. […] precisely because high prices in an OA world would exclude authors, and not merely readers, there is a natural, market-based check on excessive prices. BTW, I’m not saying that these market forces will keep prices within reach of all authors

Cameron Neylon, 2010:

I have heard figures of around £25,000 given as the level of author charge that would be required to sustain Cell, Nature, or Science as Open Access APC supported journals. This is usually followed by a statement to the effect “so they can’t possibly go OA because authors would never pay that much”.

[…]

If authors were forced to make a choice between the cost of publishing in these top journals versus putting that money back into their research they would choose the latter. If the customer actually had to make the choice to pay the true costs of publishing in these journals, they wouldn’t.

[…]

Subscription charges as a business model have allowed an appallingly wasteful situation to continue unchecked because authors can pretend that there is no difference in cost to where they publish, they accept that premium offerings are value for money because they don’t have to pay for them. Make them make the choice between publishing in a “top” journal vs a “quality” journal and getting another few months of postdoc time and the equation changes radically.

[…]

We need a market where the true costs are a factor in the choices of where, or indeed whether, to formally publish scholarly work.

Mike Taylor, 2012:

the bottom line is that paying at publication time is a sensible approach. It gives us what we want (freedom to use research), and provides publishers with a realistic revenue stream that, unlike subscriptions, is subject to market forces.

Stephen Pinfield, 2013:

But Gold OA is not like [subscription]. It has the potential to reintroduce genuine competition into the journal market with authors sensitive to price making choices about where they place their articles. If journals put APCs up, authors can go elsewhere and the adjustments can happen quickly.

[…]

Gold OA, on the other hand should make price changes clearer –and customers will be able to respond accordingly.

Danny Kingsley, 2014:

However the increase in the payment of APCs has awoken many researchers’ awareness of the costs of publication. An author’s reaction of surprise to the request for a US$3000 [approx. AU$3180] APC when they are contacted by a publisher provides an opportunity for the library to discuss the costs associated with publication. There is an argument that as payment for publication at an article level becomes more prevalent, it gives the researcher an opportunity to determine value for money and in some arguments this means that scholarly publishing would be a more functional market

Convinced that authors would be price sensitive, it was even mentioned as a problem, if someone would pay the APCs for the authors. Kingsley:

This is then one of the disadvantages of having centralised management of APCs – it once again quarantines the researcher from the cost of publication

Pinfield:

But there is a danger with many of the processes now being established by universities to pay for APCs on behalf of authors. These systems, which will allow payment to be made centrally often with block pre-payments to publishers, will certainly save the time of authors and therefore ought to be pursued, but they do run the risk of once again separating researchers from the realities of price in a way that could recreate some of the systemic failures of the subscription market.They need to be handled with caution.

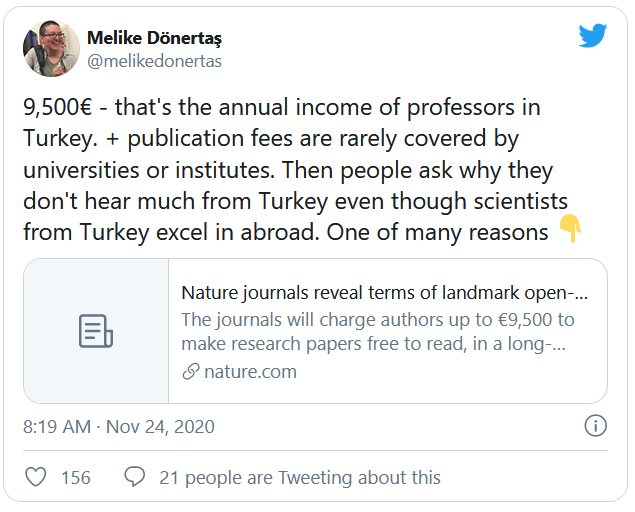

Hindsight is always 2020. Little did people know back then that authors, when faced with a choice, would actually tend to pay the most expensive APCs they could afford, because such is the nature (pardon) of a prestige market. It is as such not surprising to us now, that rich institutions hail the 10k price tag for Nature APCs as “very attractive” and “not a problem”.

The above were just the few examples I could readily find with the help of Richard Poynder, Danny Kingsley, Cameron Neylon and Mike Taylor. The sentiments expressed there were pretty much mainstream and discussed widely even before 2009 (and you can sense that in the referenced sources). Thus, the idea that high APCs are a feature and not a bug, thought to bring competition into a market was a driving force for gold OA for a long time. Even today, you can still find people claiming that “If we switch from subscription publishing to pay-to-publish open access, [publisher profit] margins are likely to drop to 10%-20%.” (Lenny Teytelman as late as 2019). We now see that this view was spectacularly wrong. People will pay no matter what when their livelihoods are at stake, even if it costs them their last shirt (German saying). We ought to think hard what the consequences now have to be, of having been so catastrophically wrong.

This is how Nature‘s high APCs came about. Many thought it was a good thing and kept pushing for them until Nature gave in.

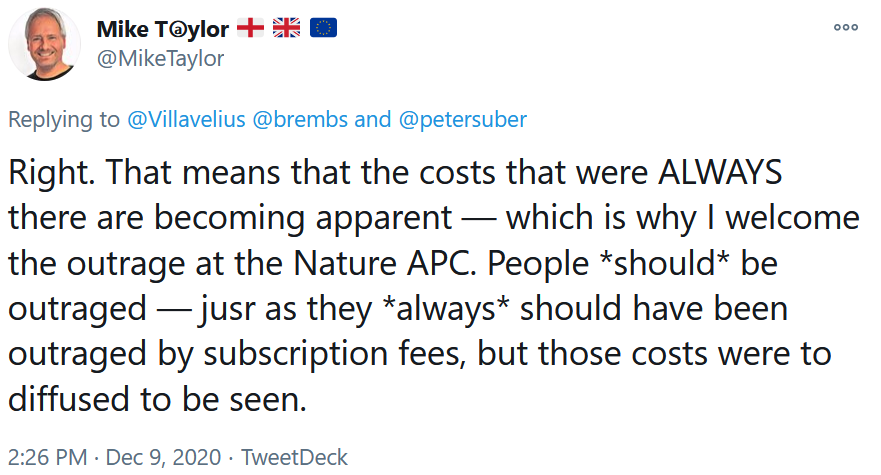

Update: One of the quoted authors, Mike Taylor, just confirmed that he still thinks 10k APCs are good and that the outrage people feel at their livelihoods being put in jeopardy is what will drive change: