Few insect behaviors are more iconic than the proverbial moths circling the lamps at night.

Artist: Dave McKean

These observations are prime examples of the supposedly stereotypic insect responses to external stimuli. In contrast, in our new paper that just appeared today, we describe experiments suggesting that insects appear to make a value-based decision before approaching the light. However, compared to us, an insect’s decisions can take very different aspects into account. For instance, when a fruit fly (Drosophila) decides whether to approach light, it takes its flying ability into account. If any parameter of flight is sufficiently compromised, it is better to hide in the shadows, whereas the full ability to fly emboldens the animal to seek out the light. In a way, these results are reminiscent of the confidence with which a certain cartoon bee approaches a window:

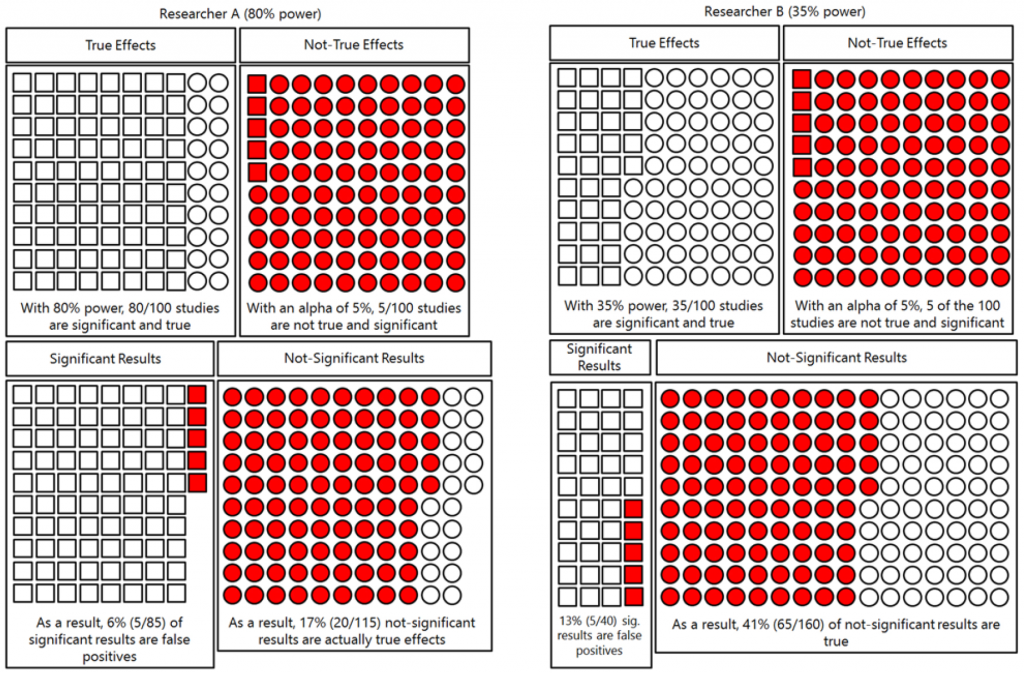

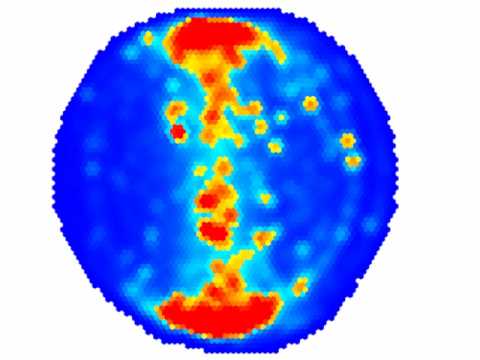

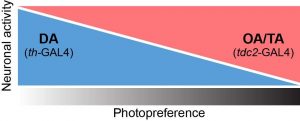

Perhaps the most beautiful result of this work is the first investigation into the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the different valuation of light (or dark) stimuli in flying and non-flying flies. We found that the tendency of flies to approach or avoid light is not an all-or-nothing decision, but that different fly strains and different manipulations of flying ability show different degrees of approach/avoidance as well as indifference. Experiments with transgenic flies showed that we can push the flies’ preference back and forth along this ‘photopreference’ gradient by activating or inhibiting neurons that secrete either dopamine or octopamine, respectively. Octopamine and Dopamine are so-called neuromodulators, known to be responsible for valuation processes in other experiments across animals and in the case of dopamine also humans. Commonly, they do this by modulating the activity of neurons involved in processing sensory stimuli, such that the value of these stimuli to the animal changes after the modulator is applied.

In our case, activating dopamine neurons made flightless flies which would otherwise avoid light, approach it. Activating octopamine neurons, on the other hand, made normal flies, which approach light, hide in the shadows, despite the manipulation leaving their flying capabilities intact. The results obtained after inhibiting these neurons were mirror symmetric: blocking dopamine neurons from firing made the flies seek darkness without affecting their flying ability. Wingless flies with their octopamine neurons blocked approached the light as if they could fly. These results inspired the following illustration of how these neuromodulators may cooperate to orchestrate the evolutionarily advantageous decision for insects when faced with a light/dark choice:

Illustration of the hypothetical balance between octopaminergic/tyraminargic (OA/TA) and dopaminergic (DA) neurons establishing the valuation of light/dark stimuli in fruit fly photopreference experiments.

Future research will show whether these same neurons indeed change their activity when the flying ability is manipulated, as one would expect from these results.

It is possible that the evolutionary origin and ultimate ethological relevance may be found in the behavior of flies which have just emerged from their pupal case. The wings of these young adults are still folded up as the insect first needs to pump blood into the veins of the wings to expand them. During this time, the flies perch underneath horizontal surfaces and avoid light. Even when the wings are fully expanded, but not capable of supporting flight just yet, this behavior persists. Only once the wings are ready for flight, do the flies perch on top of horizontal surfaces and approach light.

Adult flies in the wild that live on rotting fruit probably face the challenge of the sugary liquid of the fruit occasionally gumming up their wings, only for the next rain to wash them clean again. We mimicked this situation in one of our experiments by gluing the wings together with sucrose solution and subsequently removing the sugar glue from the flies’ wings with water. As expected, the flies approached the light before the treatment, avoided it when the wings were unusable and approached it again after the ‘shower’.

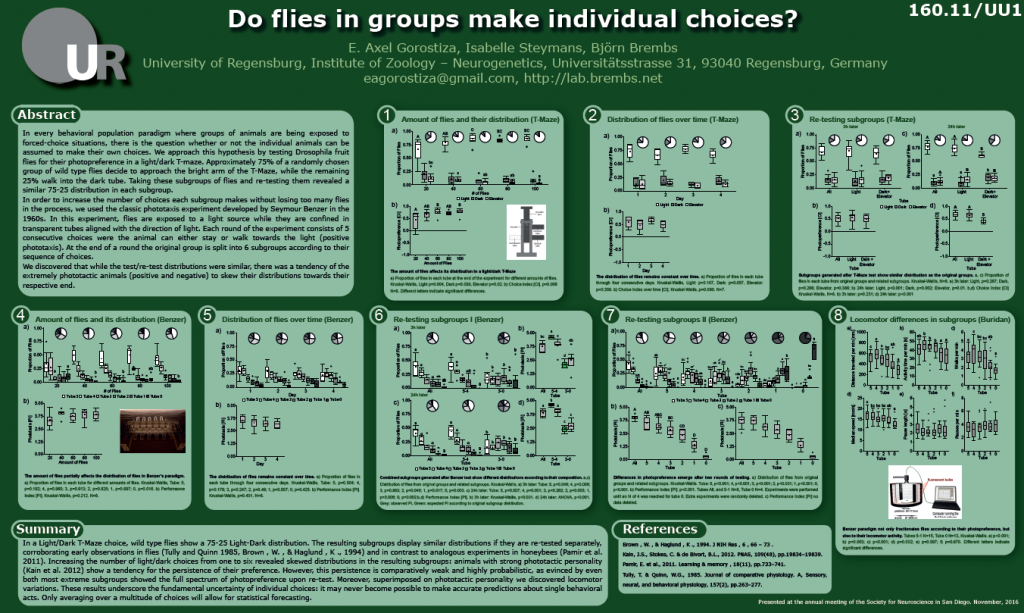

The first mention in the literature of adult flies with compromised wings being less attracted by light was by Robert McEwen in 1918. In the intervening 49 years, we could not find any mention of this phenomenon in the scholarly literature. Only in 1967, one of the founding fathers of Drosophila neurogenetics, Seymour Benzer, published work mentioning adult flies with deformed wings being less phototactic, but without any insight into the underlying neurobiology. It took yet another 49 years after Benzer’s work without any mention in the literature, before our paper described the first neurobiological components of this case of insect behavioral flexibility, 98 years after the original discoverer McEwen. Our postdoc, E. Axel Gorostiza, the first author of the paper, will start his own laboratory on this topic, so it seems unlikely that it will take yet another 49 years for the fourth publication on this topic to appear.

Of course, all our raw data are available from figshare. This was also the first paper from our laboratory where all authors were listed with their ORCID IDs and all materials and protocols were referenced with their RRIDs and protocols.io DOIs, respectively. All previous versions of the article are available as biorxiv preprints as well.

Original research article:

A Decision Underlies Phototaxis in an Insect. Royal Society Open Biology

E Axel Gorostiza, Julien Colomb, Björn Brembs

Freie Universität Berlin, Universität Regensburg, Germany.

Abstract:

Like a moth into the flame – Phototaxis is an iconic example for innate preferences. Such preferences likely reflect evolutionary adaptations to predictable situations and have traditionally been conceptualized as hard-wired stimulus-response links. Perhaps therefore, the century-old discovery of flexibility in Drosophila phototaxis has received little attention. Here we report that across several different behavioral tests, light/dark preference tested in walking is dependent on various aspects of flight. If we temporarily compromise flying ability, walking photopreference reverses concomitantly. Neuronal activity in circuits expressing dopamine and octopamine, respectively, plays a differential role in photopreference, suggesting a potential involvement of these biogenic amines in this case of behavioral flexibility. We conclude that flies monitor their ability to fly, and that flying ability exerts a fundamental effect on action selection in Drosophila. This work suggests that even behaviors which appear simple and hard-wired comprise a value-driven decision-making stage, negotiating the external situation with the animal’s internal state, before an action is selected.