While the first day (day 2, day 3) was dominated by philosophy, mathematics and other abstract discussions of chance, this day of our symposium started with a distinct biological focus.

Martin Heisenberg, Chance in brain and behavior

First speaker for this second day on the symposium on the role of chance in the living world was my thesis supervisor and mentor, Martin Heisenberg. Even if he hadn’t a massive body of his own work to contribute to this topic, just being the youngest son of Werner Heisenberg of uncertainty principle fame, made his presence interesting already from a science history perspective. In his talk, he showed many examples from the fruit fly Drosophila, which showed how the fly spontaneously chooses between different options, both in terms of behavior and in terms of visual attention. Central to his talk was the concept of outcome expectations in the organization of adaptive behavioral choice. Much of this work is published and can be easily found, so I won’t go into detail here.

Then came my talk where I presented a somewhat adjusted version of my talk on the organization of behavior, where I provide evidence how even invertebrate brains generate autonomy and liberate themselves from the environment:

Friedel Reischies, Limited Indeterminism – amplification of physically stochastic events

Third speaker this morning was Friedel Reischies, psychiatrist from Berlin. After introducing some general aspects of brain function, he discussed various aspects of the control of behavioral variability. He also talked about the concept of self and how we attribute agency to our actions, citing D. Wegner. Referring to individual psychiatric cases he talked about different aspects of freedom and how these cases differentially impinge on these aspects. Central theme of his talk was the variability of nervous systems / behavior and its control.

The discussion session after these first three talks circulated quite productively around intentionality, decision-making, free will and the concept of self.

Wolfgang Lenzen: Does freedom need chance?

The third speaker for this day was a philosopher, Wolfgang Lenzen. As it behooves a philosopher, he started out with an attempt to define the terms chance, possibility, necessity and contingency, as well as some of their variants. Here again, as yesterday, the principle of sufficient reason reared its head again. He then went back to Cicero and Augustine to exemplify the problem of free will with respect to determinism and causality. Later the determinist Hume was cited as the first compatibilist, allowing for an exception to determinism in the context of the will. Lenzen then described Schopenhauer as a determinist. Given the dominance of classical Newtonian mechanics, the determinism of the philosophers at the time are not surprising. The now dominant insights from relativity and quantum mechanics had a clear effect on the more recent philosophers. Lenzen then cited Schlick who predictably argued with the false dichotomy of our behavior either being determined or entirely random. Other contemporary determinist scholars cited were Roth and Prinz. In his (as I see it compatibilist) reply, he emphasized that free will is not dependent on the question of whether the world is deterministic. He also defined free will as something only adult humans have, that it requires empathy and theory of mind. In his view, animals do not possess free will as they do not reflect their actions. Hence, animals cannot be held responsible. Similar to other scholars, he listed three criteria for an action to be ‘free’: the person willed the action, the will is the cause of the action and the person could have acted otherwise.

Lenzen went on to disavow dualism: “there are no immaterial substances”. This implies that the soul or the mind as a complex mental/psychological human property is intimately, necessarily coupled to a healthy, material brain. It also implies that “mental causation” does not mean that immaterial mind interacts with a material brain. Mental causation can only be thought as an idea or thought being a neuronal activity which in principle or in actuality can move muscles.

Towards the end, Lenzen picked up the different variants of possibilities from his introduction to apply them to the different variants of alternative actions of an individual. At the end he recounted the story of Frankfurt‘s evil neurosurgeon as a “weird” example he didn’t find very useful.

Patrick Becker: Naturalizing the mind?

The final speaker for the day was a theologian and in my prejudice I expected pretty confuse magical thinking. I had no idea when he stated, how right I would be. Like some previous speakers, Becker also cited a lot of scholars (obviously a common method in the humanities) like Prinz, Metzinger, or Pauen. Pauen in particular served for the introduction of the terms autonomy and agency as necessary conditions for free will. In this context again, the false dichotomy of either chance or necessity being the only possible determinants of behavior, reared its ugly head. Becker went on to discuss Metzinger’s “Ego-Tunnel” and the concept of self as a construct of our brain, citing experiments such as the “rubber hand illusion“. It wasn’t clear to me what this example was meant to actually say. At the end of all this Becker presented a table where he juxtaposed a whole host of terms under ‘naturalization’ on one side and ‘common thought’ on the other side. The whole table looked like an arbitrary collection of false dichotomies to me and I again didn’t understand what the point of that was. He then picked ethical behavior as an example for how naturalization would lead to an abandonment of ethics. Here, again, the talk was full of false dichotomies such as: our ethics are not rational because some basic, likely evolved moral sentiments exist. As if it were impossible to combine the two. Not sure how that would be an answer to the question of his title. After ethics, he claimed that we would have to part with love and creativity as well if we naturalized the mind. None of what he talked about appeared even remotely coherent to me, nor did I understand how he came up with so many arbitrary juxtapositions of seemingly randomly collected terms and concepts. Similar to creationists, he posits that our empirically derived world-view is just a belief system – he even used the German word ‘Glaube’ which can denote both faith and belief. As if all of this wasn’t bad enough, at the very end, as a sort of conclusion or finale of this incoherent rambling, he explicitly juxtaposed (again!) the natural sciences and religion as equivalent, yet complementary descriptions of the world.

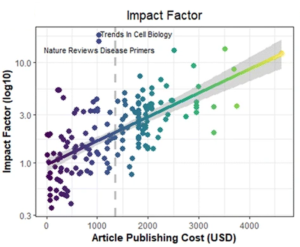

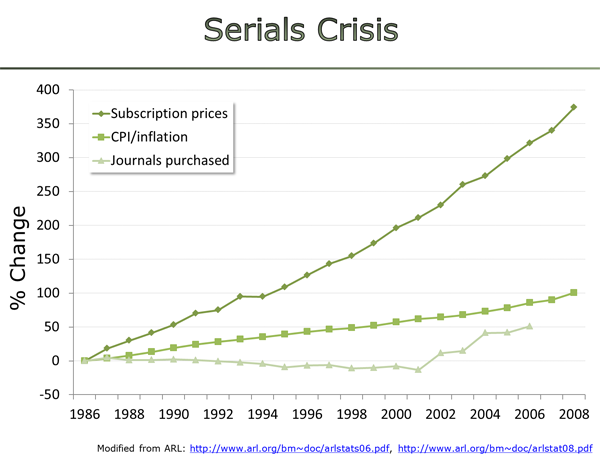

Given this publisher track record, I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.

Given this publisher track record, I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.