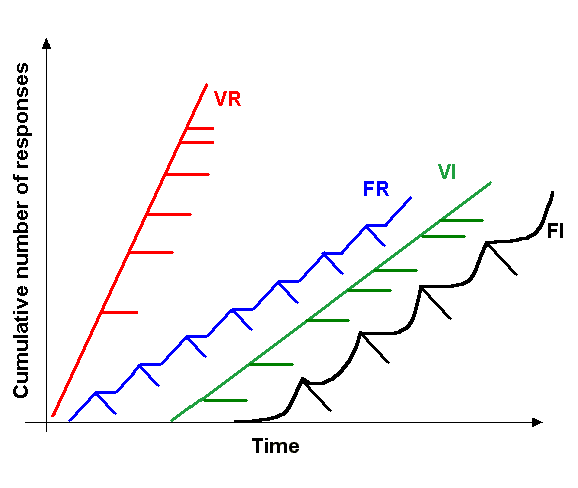

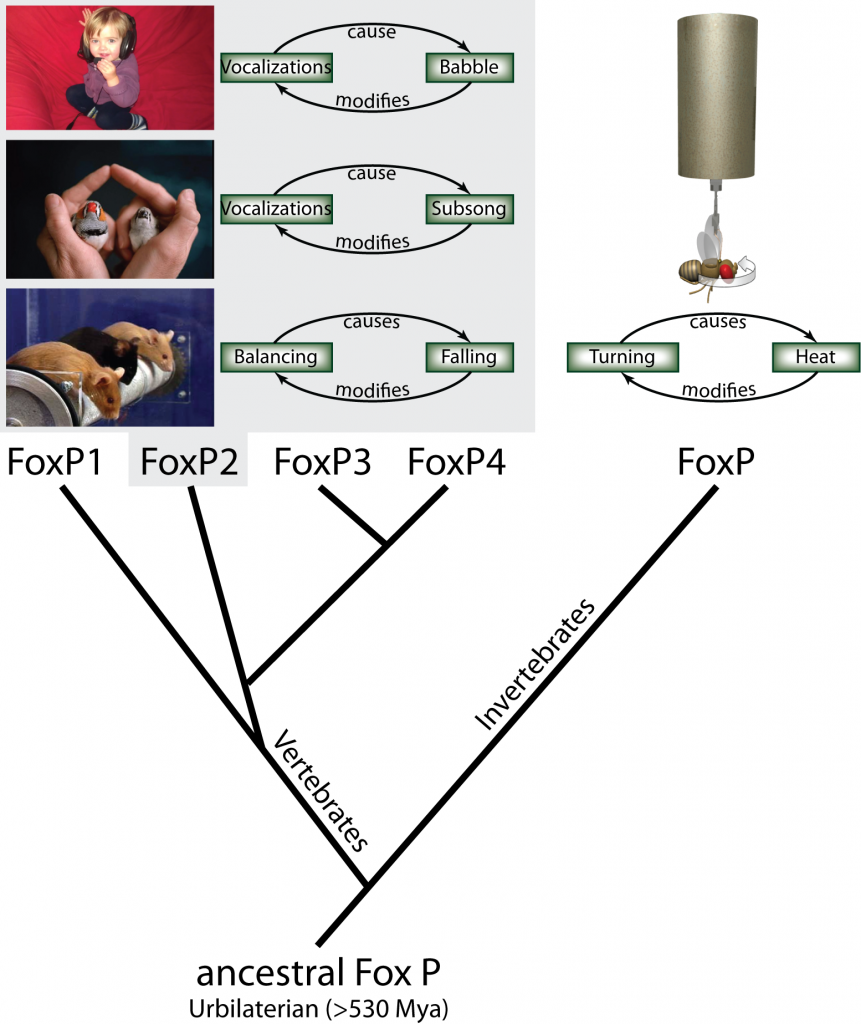

This is the story behind our work on the function of the FoxP gene in the fruit fly Drosophila (more background info). As so many good things, it started with beer. Troy Zars and I were having a beer on one of the ICN evenings, I think it was in Vancouver in 2007. I had recently learned about the conserved role of FoxP2 in songbirds, out of one of the labs in Berlin, where I was based at the time. As already Skinner had proposed that language learning was an operant conditioning process and as song learning in birds was also often characterized as a form of operant learning, I wondered aloud how cool it would be if flies had such a gene and we could test them in our operant learning experiments as well. This would really suggest a possibility to unify vocal learning and operant learning in a single biochemical pathway.

This is the story behind our work on the function of the FoxP gene in the fruit fly Drosophila (more background info). As so many good things, it started with beer. Troy Zars and I were having a beer on one of the ICN evenings, I think it was in Vancouver in 2007. I had recently learned about the conserved role of FoxP2 in songbirds, out of one of the labs in Berlin, where I was based at the time. As already Skinner had proposed that language learning was an operant conditioning process and as song learning in birds was also often characterized as a form of operant learning, I wondered aloud how cool it would be if flies had such a gene and we could test them in our operant learning experiments as well. This would really suggest a possibility to unify vocal learning and operant learning in a single biochemical pathway.

“Shhh, don’t tell anybody, I have them!”, Troy replied.

It turned out that at the time, the FoxP-related gene in flies had not been annotated in the genome yet. Troy had performed the database sequence search and performed some preliminary molecular experiments to make sure he really had the dFoxP gene. He even noticed that one sequence just downstream of the gene was in fact the last exon of the gene and that the automated curation process had missed this detail. He had ordered three fly lines each with one insertion mutation in or near this last exon and replaced the rest of the genome with the background of a control strain in his lab, “Canton S”. He even had done some preliminary behavioral tests on the courtship of these ‘cantonized’ lines.

We agreed that he would send me the lines and I would test them in our operant conditioning experiments. When I received the lines I was excited and started testing them as soon as they hatched. The first day was a disappointment: I had randomly chosen one of the three lines and tested a few of them along with Troy’s Canton S control flies. Both groups learned just fine. I was almost going to give this up as a beautiful hypothesis slain by an ugly fact, when I reminded myself that one should not rest one’s conclusions on a single day of testing. So I decided to test them at least for the rest of the week and then see what happened. On each of the following days, learning scores were consistently zero, such that, by the end of the week, the combined score of all the animals didn’t look all that good any more. The final results, several weeks later, can now be seen in Fig. 3 of our paper.

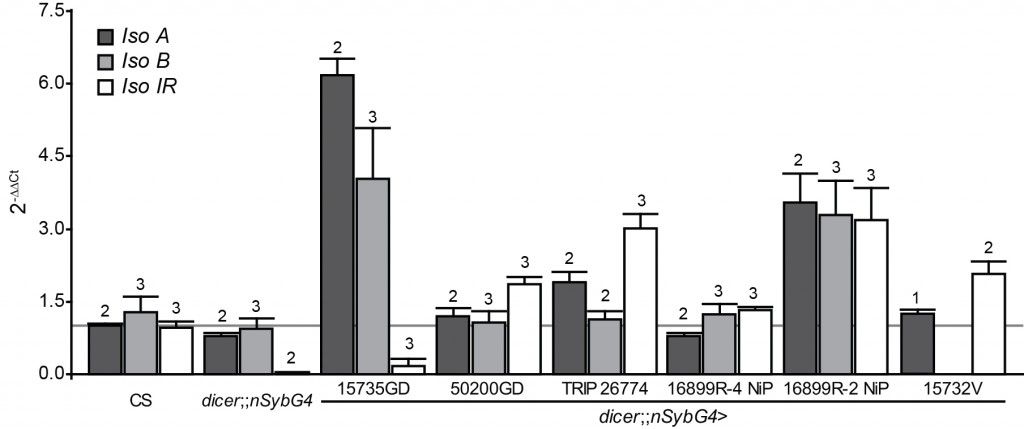

In order to find out what was going on with FoxP gene expression in these mutants, FoxP2 specialist Constance Scharff in the neighboring department of behavioral biology in Berlin teamed up with Jochen Pflüger in our department to apply for some funding for this project. The results of this fruitful collaboration can be seen in Figs. 2 and 5c. It was then graduate student, now postdoc Ezequiel Mendoza who did all the molecular biology.

Because FoxP genes are transcription factors regulating the expression of other genes during brain development, I was curious if the brain structure of these flies were any different from control flies. Jürgen Rybak was a specialist on insect brain anatomy and had recently left the department in Berlin. I gave him two vials of flies and asked him if he could quantify the main brain regions ‘on the side’ of his regular day job at the Max Planck Institute. Jürgen worked tirelessly and after many months of slogging came up with some very subtle results, now depicted in Fig. 6. To this day, we’re still unsure what these data really ought to tell us, other than that FoxP also in flies is involved in brain structure and development. This figure, btw, has two examples of fly brains that you would be able to rotate and zoom in and out of in 3D, if PLoS would be able to support 3D PDF files. As they don’t, you have to dig into the supplemental information, go to Fig. S3 there and open the PDF file. Then, if you click on any or both of the brains, you can use the 3D functionality we have embedded there.

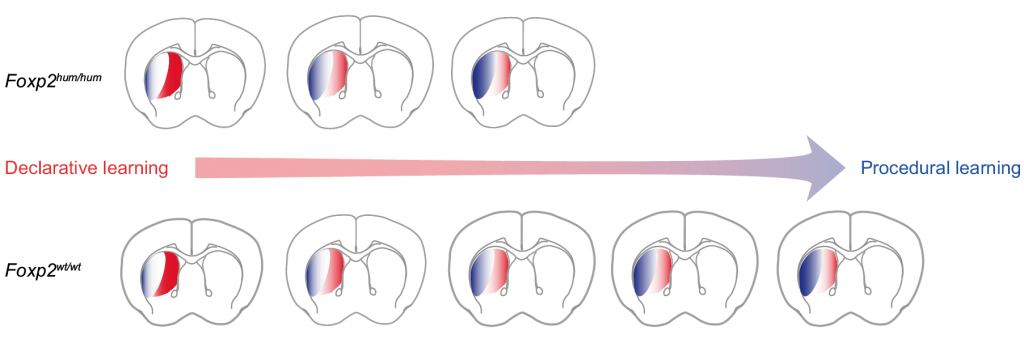

Another parallel between vocal learning and operant conditioning is the observation that training/practicing for extended periods of time leads to a stereotypization or automatization of the behavior trained. In songbirds, this is called “crystallization” of the song, in operant conditioning it is called habit formation. Flies show this sort of habit formation as well, but we had no idea if it was the same process as the much quicker form of learning we had tested before, or if this was something that looked similar on the behavioral level, but the neurobiology was quite distinct. So the postdoc in our lab at the time, Julien Colomb, set out to not only replicate my own results with the FoxP mutants, but to also test the much trickier habit formation experiment in the mutant flies, using his own, new machine. He found that indeed these flies were also deficient in habit formation, replicating not only my results, but also strongly suggesting that our form of operant learning (which we have termed “operant self-learning”) and habit formation are likely biochemically the same process.

Because having just one mutant allele (the other two lines did not fly well enough for our experiments) is not enough evidence to conclusively tie these phenotypes to the FoxP gene, we took advantage of the fact that the last exon, where the insertion mutation resided, was initially listed as a separate gene in the databases. The method of choice was to attempt to knock-down dFoxP expression using RNAi. We wanted to mimick the original mutation as specifically as possible, so we wanted only to knock down the dFoxP isoforms which included the last exon. Usually, this is not possible, without designing your own transgenic constructs. However, because the last exon was its own gene in the databases, there was a line that contained an RNAi construct for just the last exon. So I ordered that line, crossed it to another line that would express the RNAi construct specifically in all neurons and tested the flies. This was when I started to get very, very nervous: the flies with the RNAi-targeted dFoxP also did not learn in operant self-learning! In most of my research career, things have turned out the opposite of what I had expected, in almost all of my experiments. Did I do something, subconsciously, to bias my results? After all, this was now the second experiment in a row that turned out just as one would dream of! I couldn’t find anything wrong, measured yet more flies in different crosses just to be sure, but the result remained the same. As long as nobody else finds out what went wrong, I have to accept the data and acknowledge that one of my hypotheses turned out to be correct for once after all. That’s a very weird and strangely disconcerting feeling.

Everything had been smooth sailing so far, so clearly, there had to be something that would put a spoke in our wheels. We decided to submit the manuscript to PNAS just before the winter break in 2011, on December 21, with the title “Drosophila FoxP is necessary for operant self-learning”. One reviewer liked it, but the other summarized their review by

the data are made to bear the weight of an elaborate hypothesis, and they are literally crushed by it, like a tiny matchstick house beneath a bowling ball.

The reviewer appeared particularly miffed by something he hadn’t heard of before:

to the best of my knowledge the distinction between operant self-learning and operant world-learning is one that is not widely acknowledged in the learning and memory community. Indeed, the senior author and his colleagues of this manuscript may be the only people in the world who hold that there is such a distinction.

We dared to submit something that wasn’t yet part of the wider learning and memory community! How preposterous! It appears that this reviewer was not very keen on new discoveries – only processes and observations “widely acknowledged by the community” should be published. Novel, groundbreaking or controversial findings need not be submitted. A very strange perspective to take for a scientist indeed, especially since at the point of submission we already had two peer-reviewed papers with this distinction published. The reviewer struck the death blow to the paper:

If one strips away the elaborate theoretical superstructure of this paper, for which the evidence is, I believe, shaky at best, what is one left with? Basically, the authors have shown that a FoxP fly mutant performs abnormally on one operant conditioning task, but normally on another. This is well and good, but not, to my mind, sufficient for a PNAS paper.

And of course, the classic smack down that will kill any paper, but at least to my mind is essentially unethical: ask for virtually every single potential experiment to be made:

To accept the authors’ ideas, we would have to know whether or not FoxP mutant flies are deficient in other forms of learning. In other words, what is the evidence that the learning abnormalities in these flies are confined to “self-learning” motor tasks? Remarkably, the authors do not test their mutants on any of the other learning tasks available for Drosophila, among which are olfactory conditioning, habituation and conditioning of proboscis extension, and nociceptive sensitization. Knowing the full range of learning dysfunctions of FoxP mutants would help clarify the important issue of whether or not this class of genes is devoted to operant self-learning as the authors believe.

Not one, not two, but 4 different behavioral experiments is what we should do, topped up by “the full range of learning dysfunctions”. If any reviewer for any of the papers I’m handling as an editor ever should request anything like that from one of the authors, I will definitely report the person to his department for unethical behavior: asking for every experiment on the planet is just something that gives away bias. But that’s not even enough. On top of doing every single behavioral learning experiment the world knows for flies, we should also do a full-scale molecular genetic interaction study:

It would also be important to know whether or not FoxP mutants have defects in PKC signaling. Does Drosophila FoxP even have a PKC binding site? Can overexpression of PKC isoforms in flies rescue the learning deficits of the FoxP mutants?

Asking for essentially a decade or two of experiments in a review for a single paper is clearly unethical in my books and I notified PNAS of that. Obviously, other than acknowledgment of receipt, I never heard of them again. I guess there may be something to the talk and gossip about PNAS…

We decided to instead submit our work to PLoS One, after we tried and tackled the more reasonable suggestions by the other reviewer. In April 2012, we’re ready and submitted the revised manuscript. In May, we got a ‘major revisions’ notification, asking us to essentially replace the semi-quantitative PCR with quantitative PCR when we test for the effectiveness of the RNAi procedure. I thought this was a good and reasonable suggestion as I had started to become suspicious that the regular PCR was quite liable to false bands: both missing and appearing bands.

It took us more than a year to get the qPCR data, evaluate them and digest them: it had turned out that the RNAi had not knocked down the dFoxP mRNA in any way we would be able to detect. Thus, it was possible that the behavioral phenotype was due to another gene, serendipitously affected by the RNAi construct (a so-called ‘off-target effect’). This left us with just one allele and an inconclusive RNAi result. I researched the literature as I had recently been teaching the RNAi method to undergraduates and had taught that under some conditions, the mRNA is not degraded, but sequestered. Now what were these conditions again? In brief, if the match between RNAi construct and target region of the gene is not 100%, the mRNA is rather sequestered, than chopped up. So we (i.e., Ezequiel) cloned and sequenced this region for all of our lines and did indeed find several mismatches in the target region. Lucky to have an explanation for a phenotype without mRNA knockdown, but nervous that it wouldn’t be sufficient, we re-submitted in August 2013.

As we feared, the reviewers did not find our explanations sufficient and again sent us the manuscript back. In the meantime, I had moved to Regensburg from Berlin and discussed the paper with colleagues at lunch. One of them, José Botella-Munoz, suggested I try a classic genetic experiment from the 20th century: cross the mutants and the controls over a deficiency that spans the dFoxP locus! I ordered the flies, crossed and tested them and to our relief, the results confirmed that the mutation in the FoxP genes was the most likely culprit for the learning phenotype. Find these results now in Fig. 4 of the paper. In addition to these results, we also changed the title to “Drosophila FoxP mutants are deficient in operant self-learning”, as we still can’t fully rely on the RNAi data.

During the revision process, what all of us secretly feared happened: another behavioral fly FoxP paper was published. These authors had not done any learning experiments, but had found an involvement of FoxP with motor problems of the flies. However, they relied heavily on the RNAi method, but without using qPCR, only the regular PCR which was the reason our manuscript was initially rejected at PLoS. So that was something of a shock, but not too bad, at least not for the authors (other colleagues got hit worse by some of the results in this paper). Just days before we submitted what would become our final version, Science published a paper on FoxP in flies that flew in the face of everything published about FoxP genes so far, but apparently without exchanging the genetic background of the mutants, without meticulous controls to rule out motor defects and without even attempting to test for the efficiency of the RNAi procedure. There is a more in-depth treatment of this paper in my previous post. Either way, we have several posters and blog posts to show that we were on dFoxP already several years ago.

Now, finally, more than 2.5 years after the initial first version of the manuscript was submitted to PNAS, our work is finally published in PLoS One and it will be exciting to see if now others can find the mistake we couldn’t find and show us why this is all wrong 🙂

Mendoza, E., Colomb, J., Rybak, J., Pflüger, H., Zars, T., Scharff, C., & Brembs, B. (2014). Drosophila FoxP Mutants Are Deficient in Operant Self-Learning PLoS ONE, 9 (6) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100648

Like this:

Like Loading...