For ages I have been planning to collect some of the main aspects I would like to see improved in an upgrade to the disaster we so euphemistically call an academic publishing system. In this post I’ll try to briefly sketch some of the main issues, from several different perspectives.

As a reader:

I’d like to get a newspaper each morning that tells me about the latest developments, both in terms of general science news (aka. gossip) as well as inside my scientific fields of interest. For the past 5+ years, my paper.li has been doing a pretty decent job at collecting the gossip, but for the primary literature relevant to my field, such a technology is sorely missing. I’d like to know which papers my colleagues are reading, citing and recommending the most. Such a service would also learn from what I click on, what I recommend and what I cite, to assist me in my choices. Some of these aspects are starting to be addressed by companies such as F1000 or Google Scholar, but there is no comprehensive service that covers all the literature with all the bells and whistles in a single place. We have started to address this by developing an open source RSS reader (a feedly clone) with a plug-in functionality to allow for all the different features, but development has halted there for a while now. So far, the alpha version can sort and filter feeds according to certain keywords and display a page with the most tweeted links, so it’s already better than feedly in that respect, but it is still alpha software. All of the functionalities I want, have already been developed somewhere, so we’d only need to leverage them for the scientific literature.

In such a learning service, it would also be of lesser importance if work was traditionally peer-reviewed or not: I can simply adjust for which areas I’d like to only see peer-reviewed research and which publications are close enough that I want to see them before peer-review – I might want to review them myself. In this case, peer-review is as important as I, as a reader, want to make it. Further diminishing the role of traditional peer-review are additional layers of selection and filtering I can implement. For instance, I would be able to select fields where I only want recommended literature to be shown, or cited literature, or only reviews, not primary research. And so forth, there would be many layers of filtering/sorting which I could use flexibly to only see relevant research for breakfast.

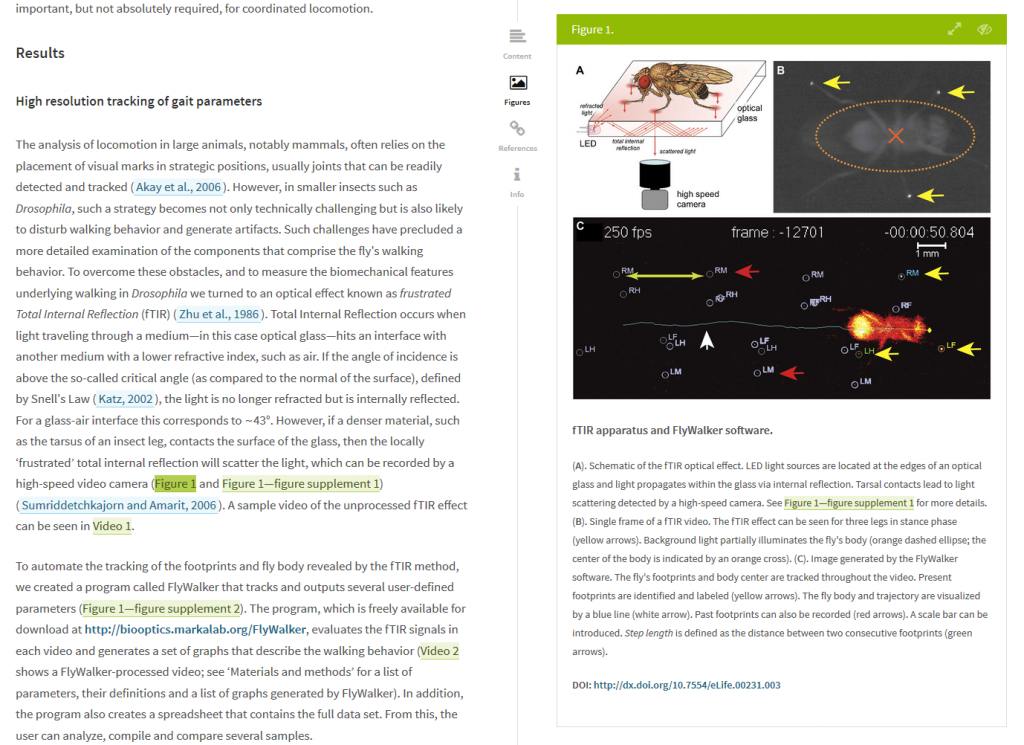

I admit it, I’m a fan of Lens. This is an excellent example of how scientific content should be displayed on a screen. With a modern infrastructure, we get to choose which way we would like to read, Lens would not be the only option besides emulating paper. Especially when thorough reading and critical thinking are required, such as during the review of manuscripts or grant proposals, ease of reading and navigating the document is key to an efficient review process. In the environment we already should have today, reviewers would be able to pick the for them most efficient way of thoroughly fine-combing a document.

We would also be able to click on “experiments were performed as previously described” and then directly read the exact descriptions of how these experiments were done, because we would have finally have implemented a technology from 1968, hyperlinks. Fully implementing hyperlinks would also provide the possibility to use annotations to the literature: such annotations, placed while reading, can later be used as anchors for citations. Obviously, we’d be using a citation-typology in order to make the kind of citation (e.g. affirmative or dismissive, etc.) we intended machine readable.

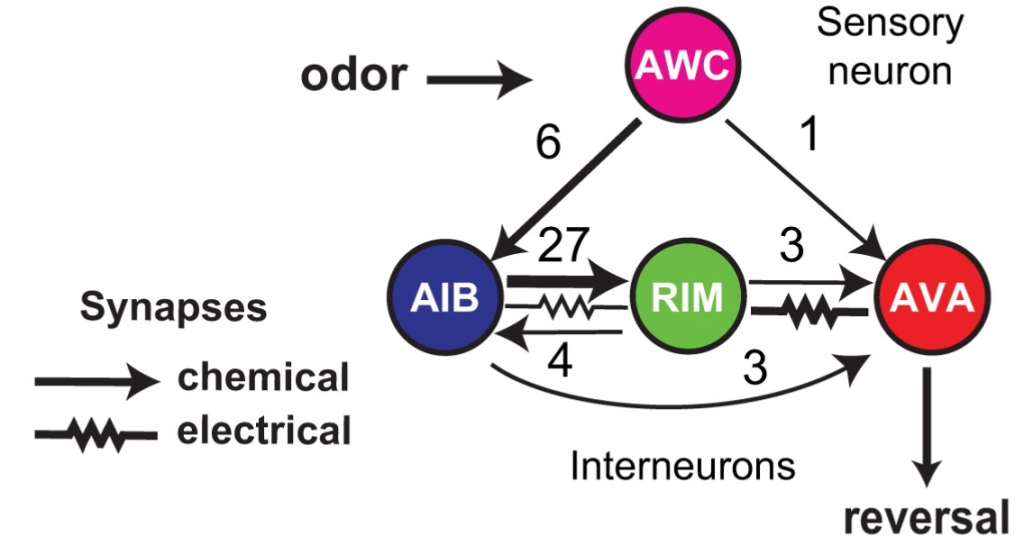

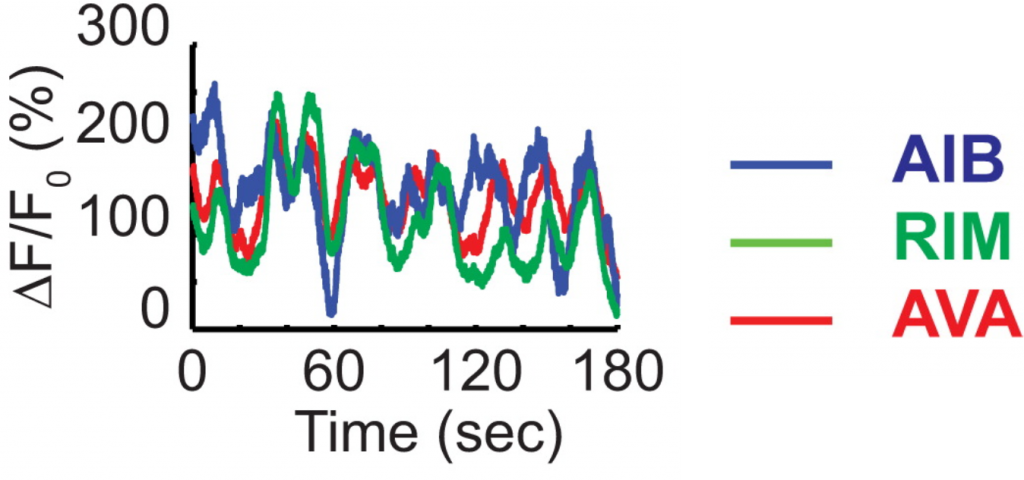

Of course, I would also be able to double-click on any figure to have a look at other aspects of the data, e.g. different intervals, different intersections, different sub-plots. I’d be able to use the raw data associated with the publication to plot virtually any graph from the data, not just those the authors offer me as a static image, as today. How can this be done? This brings me to the next aspect:

As an author:

As an author, I want my data to be taken care of by my institution: I want to install their client to make sure every piece of data I put on my ‘data’ drive will automatically be placed in a data repository with unique identifiers. The default setting for my repository may be open and a CC0 license, or set manually to any level of secrecy I’m allowed to or intend. The same ought to be a matter of course for the software we write. In today’s day and age, institutions should provide an infrastructure that makes version-controlled software development and publishing seamless and effortless. And yet, we, the scientists, have to ask our funders for money to implement such technology. Likewise for authoring: we need online authoring tools that can handle and version-control documents edited, simultaneously, by multiple authors, including drag and drop reference managing. GDocs have been around for a decade if not more and FidusWriter or Authorea are pioneering this field for scientific writing, but we should already have this at our institutions by default today (with local copies, obviously).

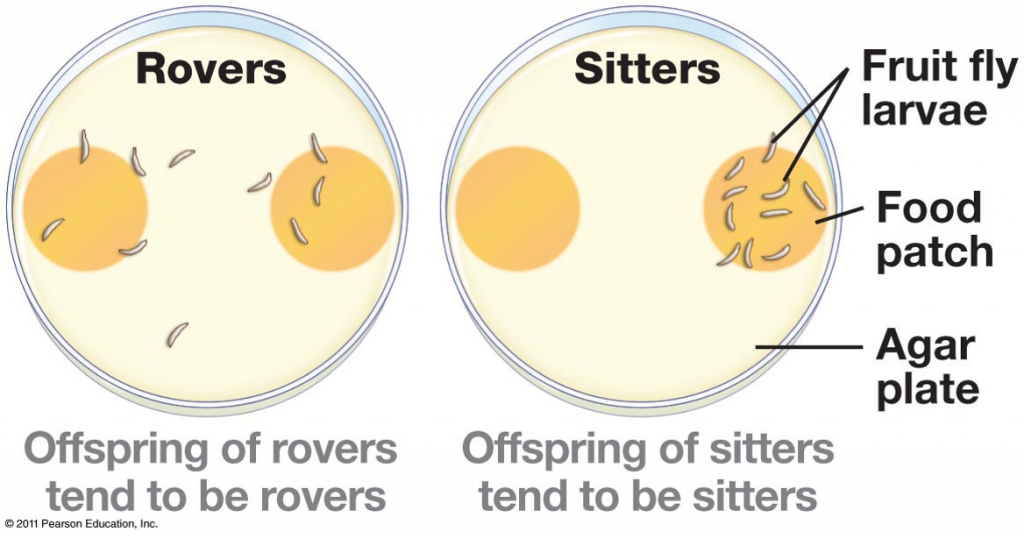

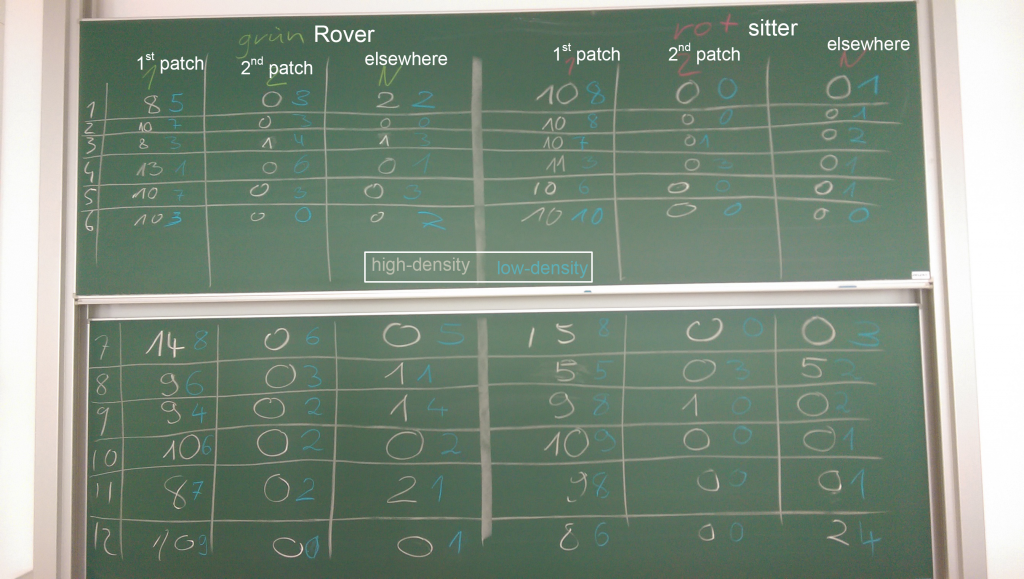

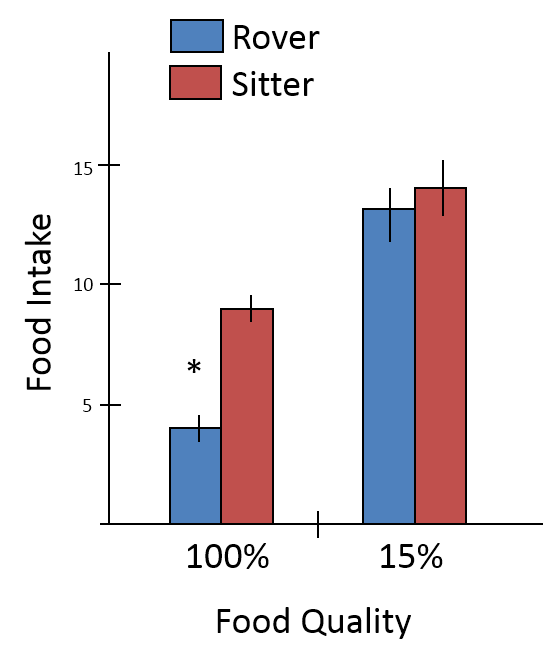

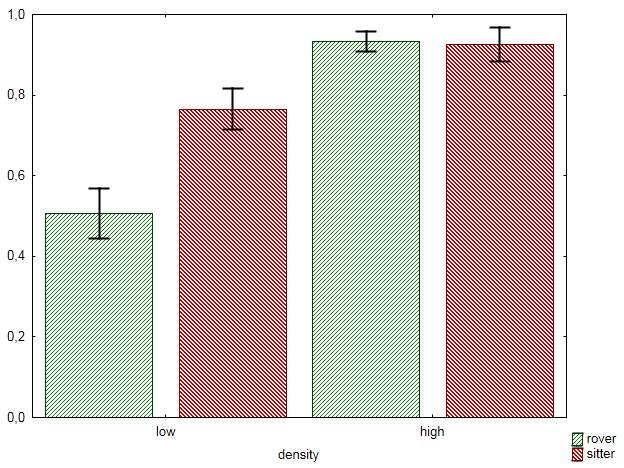

If we had such GitHub-like infrastructure, a figshare/DropBox combo that took care of our data and an Authorea/FidusWriter authoring environment, we could routinely do what we have done as a proof of principle in our latest paper: When you write the paper, you don’t have to artificially design any actual figures any more. The authors just insert the code that calls the software to evaluate the linked, open data. This allows the reader to not only generate their own figures from different perspective from our data (as in Fig. 3 of our paper), they can also download all the code and data without asking us and without us having to jump through any extra hoops to make our code/data available – it all happens on the invisible back-end. Had we been able to use Authorea/FidusWriter, submission would even have been just a single click. I get furious every time I estimate the amount of time and effort I could save if this infrastructure were in place today, as it should be.

Another thing one could do with such an infrastructure would be to open up certain datasets (and hence figures) to contributions from other labs, e.g. to let others compare their own results with yours. We demonstrated this “hey look what we found, how does that look for you?” kind of functionality in Fig. 4.

More or less automated semantic tagging would allow us to leverage the full potential of semantic web technology in order to facilitate some of the features I haven’t yet been able to imagine.

As a reviewer:

A reviewer is a special kind of reader, quite obviously. As such, all the above-mentioned features would also benefit the reviewer. However, there is a feature that is special for the reviewer: direct, if need be anonymized discussions with the author of a manuscript or proposal under review. Of course, this discussion would be available with the final version of the paper, where appropriate. In this discussion, the reviewers (invited, suggested and voluntary) and authors would be working on a fully annotated version of the manuscript, significantly reducing the time required for reviewing and revising manuscripts. Editors would only ever come in to help solve any points of contention that cannot be resolved by reviewers/authors themselves. Some publishers already implement such discussion to some extent, but none that I know of use an authoring environment, as would be the rational solution.

As an evaluator:

There is no way around reading publications in order to evaluate the work of scientists. There are no shortcuts and no substitutes. Reading publications is a necessary condition, a conditio sine qua non, for any such evaluation. However, it is only a sufficient criterion in the best of all worlds. Only in a world without bias, misogyny, nepotism, greed, envy and other human shortcomings, would reading publications be sufficient for evaluating scientific work. Unfortunately, some may say, scientists are humans and not immune to human shortcomings. Therefore (and because the genie is out of the bottle), we need to supplement expert judgment with other criteria. These criteria, of course, need to be vetted by the scientific method. The current method of ranking journals and then ranking scientists according to where they know the editors of such journals is both anti-scientific and counter-productive.

If we had a fully functional infrastructure possible with today’s technology, we’d be able to collect data from each scientist with regard to their productivity (data, code, publications, reviews), popularity (downloads, media presence, citations, recommendations), teaching (hours, topics, teaching material) or service (committees, administration, development). To the extent that this is (semi-)automatically possible, one could even collect data about the methodological soundness of the research. If we, as a scientific community, hadn’t spent the last 20 years in a digital cave, we’d be discussing about the ethics of collecting such data, about how these data are or are not correlated with one another, about the degree of predictive power of some of these data for future research success and other such matters – and not about how we one day might be able to actually arrive in the 21st century.

—

All of the functionalities mentioned above (and many more I haven’t mentioned) are already being tried here and there to various degrees and in various combinations. However, as standalone products none of them are really going to ever be more than just interesting ideas, proofs of concept and demonstrations. What is required is an integrated, federated backbone infrastructure with a central set of standards, into which such functionalities can be incorporated as plug-ins (or ‘apps’). What we need for this infrastructure is a set of open, evolvable rules or standards, analogous to TCP/IP, HTTP and HTML, which can be used to leverage key technologies for the entire community at the point of development – and not after decades of struggle against corporate interests, legal constraints or mere incompetence.

It is also clear that this infrastructure needs to be built robustly. Such a core infrastructure cannot rely on project funds or depend on the whims of individual organizations, even if they be governments. In fact, the ideal case would be a solution similar or analogous to BitTorrent technology: a world-wide, shared infrastructure where 100% of the content remains accessible and operational even when 2/3 of the nodes go offline. Besides protecting scholarly knowledge against funding issues and the fickleness of individual organizations, such a back-end design could also protect against catastrophic regional devastations, be they natural or human made.

Such technology, I think that much is clear and noncontroversial, is readily available. The money, is currently locked up in subscription funds, but cancellations on a massive scale are feasible without disrupting access much and will bring in just over US$9b annually – more than enough to build this infrastructure within a very short timeframe. Thus, with money and technology readily available, what’s keeping the scientific community from letting go of antiquated journal technology and embracing a modern scholarly communication infrastructure? I’ve mentioned human shortcomings above. Perhaps it is also an all too human shortcoming to see the obstacles towards such a modern infrastructure, rather than its potential:

Or, as one could also put it, more scientifically: “The square traversal process has been the foundation of scholarly communication for 400 years!”

@brembs "The square traversal process has been the foundation of scholarly communication for 400 years."

— Ian McCullough is @bookscout (@bookscout) April 27, 2015

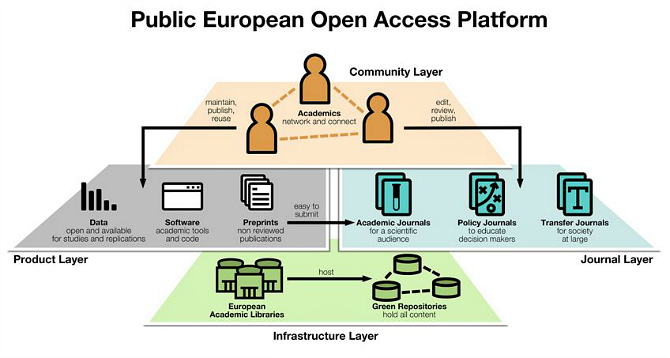

UPDATE (11/04/2017): There has been a recent suggestion as to how such an infrastructure ma be implemented conceptually. It still contains the notion of ‘journals’, but the layered structure explains quite well how this may work: