Due to ongoing discussions on various (social) media, this is a mash-up of several previous posts on the strategy of ‘flipping’ our current >30k subscription journals to an author-financed open access corporate business model.

I consider this article processing charge (APC)-based version of ‘gold’ OA a looming threat that may deteriorate the situation even beyond the abysmal state scholarly publishing is already in right now.

Yes, you read that right: it can get worse than it is today.

What would be worse? Universal gold open access – that is, every publisher charges the authors what they want for making the articles publicly accessible. Take the case of Emerald, a publisher which recently raised their APCs by a whopping 70%. When asked for the reason for their price-hike, they essentially answered “because we can“:

The decision, based on market and competitor analysis, will bring Emerald’s APC pricing in line with the wider market, taking a mid-point position amongst its competitors.

Quite clearly, publishers know their market and know how much they can extract from it (more to that below).

(UPDATE, 13.04.2018: There is data that also Frontiers is starting to milk the cash cow more heavily now, with APC price hikes of up to 40%, year over year)

Already a few years ago. a blog post by Ross Mounce described his reaction to another pricing scheme:

Outrageous press release from Nature Publishing Group today.

They’re explicitly charging more to authors who want CC BY Gold OA, relative to more restrictive licenses such as CC BY-NC-SA. Here’s my quick take on it: https://rossmounce.co.uk/2012/11/07/gold-oa-pricewatch

More money, for absolutely no extra work.

How is that different from what these publishers have been doing all these years and still are doing today? What is so surprising about charging for nothing? That’s been the modus operandi of publishers since the advent of the internet.

Why should NPG not charge, say, US$20k for an OA article in Nature, if they chose to do so? In fact, these journals are on record that they would have to charge around US$50,000 per article in APCs to maintain current profits (more like US$90,000 per article today, see update below).

If people are willing to pay more than 230k ($58,600 a year) for a Yale degree or over 250k ($62,772 a year) just to have “Harvard” on their diplomas, why wouldn’t they be willing to shell out a meager 90k for a paper that might give them tenure? That’s just a drop in the bucket, pocket cash. Just like people will go deep into debt to get a degree from a prestigious university, they will go into debt for a publication in a prestigious journal – it’s exactly the same mechanism.

If libraries have to let themselves get extorted by publishers because of the lack of support of their faculty now, surely scientists will let themselves get extorted by publishers out of fear they won’t be able to put food on the table nor pay the rent without the next grant/position. Without regulation, publishers can charge whatever the market is willing and able to pay. If a Nature paper is required, people will pay what it takes.

Speaking of NPG, they are already testing the waters of how high one could possibly go with APCs. While the average cost of a subscription article is around US$5,000, NPG is currently charging US$5,200 plus tax for their flagship OA journal Nature Communications. So in financial terms at least, any author who publishes in this journal becomes part of the problem, despite the noble intentions of making their work accessible. At this level, gold OA becomes even less sustainable than current big subscription deals.

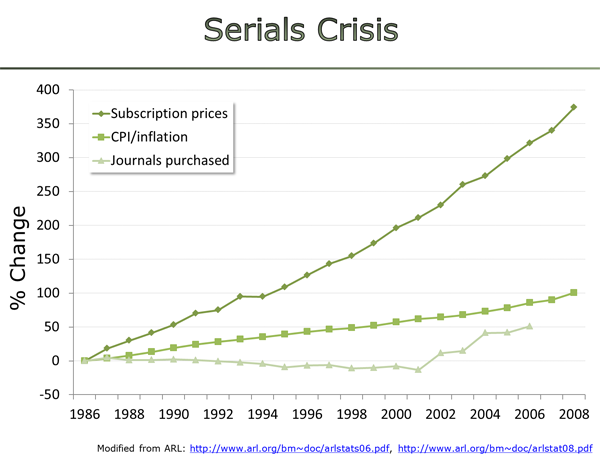

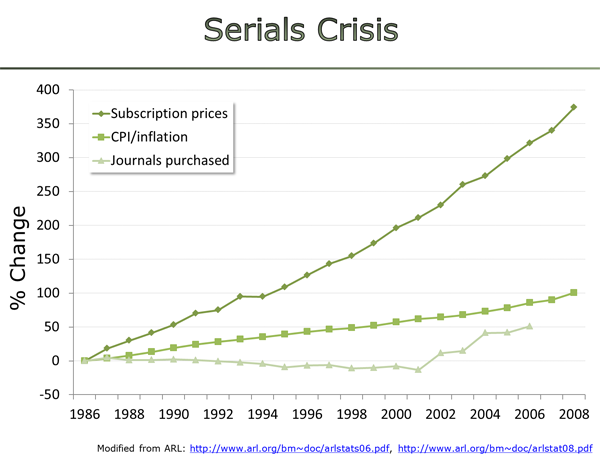

Of course, this is no surprise. After all, maximizing profits is the fiduciary duty of corporate publishers. For this reason, the recent public dreaming about how one could just switch to open access publishing by converting subscription funds to APCs are ill-founded. Proponents may argue that the intent of the switch is to use library funds to cover APC charges for all published articles. This is a situation we have already had before. This is what happens when you allow professional publisher salespeople to negotiate prices with our unarmed and unsupported academic librarians – hyperinflation:

Given this subscription publisher track record (together with the available current evidence of double digit percentage APC increases by NPG, Emerald or Frontiers, or the already now above-inflation increase in APCs more generally), I think it is quite reasonable to remain somewhat skeptical that in the hypothetical future scenario of the librarian negotiating Big Deal APCs with publishers, the publisher-librarian partnership will not again be lopsided in the publishers’ favor.

The current scholarly publishing market is worth round US$10bn annually, so this is what publishers will shoot for in total revenue. In fact, if a lesser service (subscriptions) was able to extract US$10bn, shouldn’t a better service (open access) be able to extract 12 or 15bn from the public purse? Hence, any cost-savings assumed to come from corporate gold OA are naive and completely imaginary at this point.

In fact, if the current reluctance to cancel/not renew the more and more obsolete subscriptions is anything to go by, such Open Access Big Deals will be even more of a boon for publishers than subscriptions. The most cited reason for continued subscription negotiations and contracts is perceived faculty demand. One needs to emphasize that this demand here merely constitutes unwillingness to spend a few extra clicks or some wait time to get the article, in most cases. In contrast, when the contracts are about APCs, they do not concern read-access, but write-access. If a library were to not pay a Big APC Deal any more, it would essentially mean that their faculty would be unable to publish. Hence, if librarians now worry about the consequences of their faculty having to click a few extra times to get an article, they ought to be massively worried what happens when their faculty can’t publish in certain venues any more. Faculty response will be disproportionately more vicious, I’d hazard a guess.

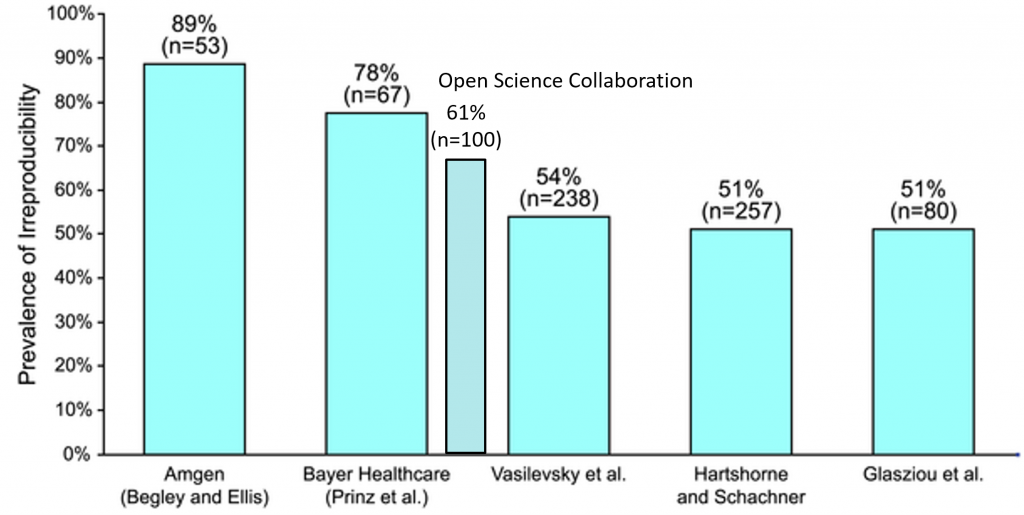

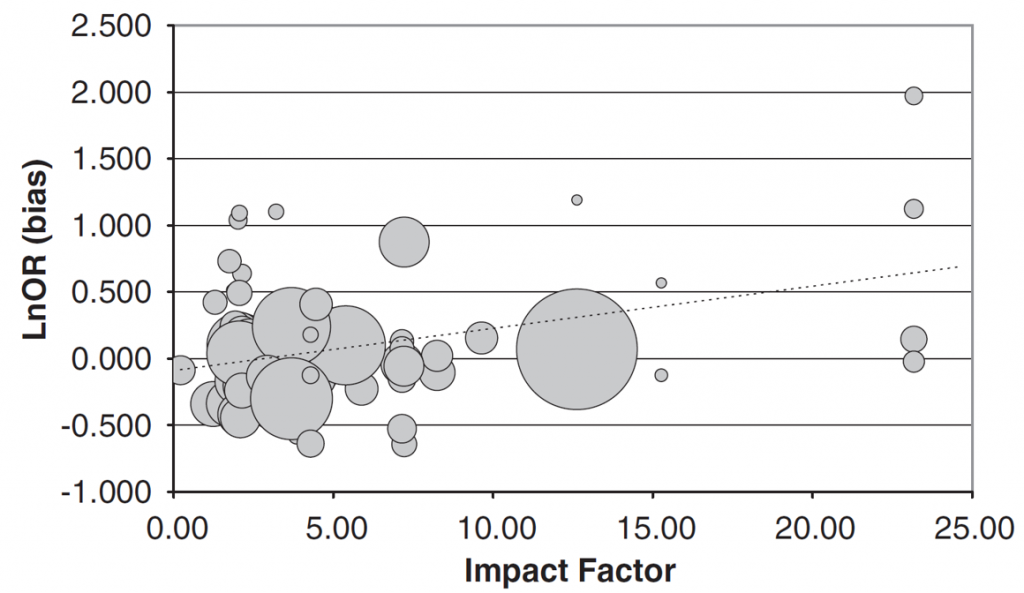

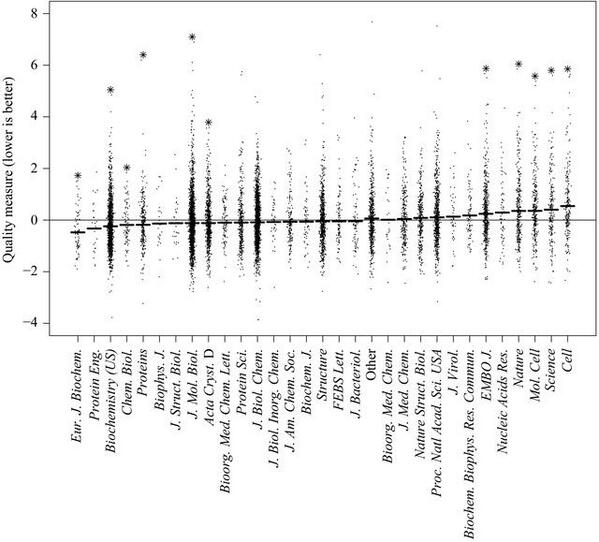

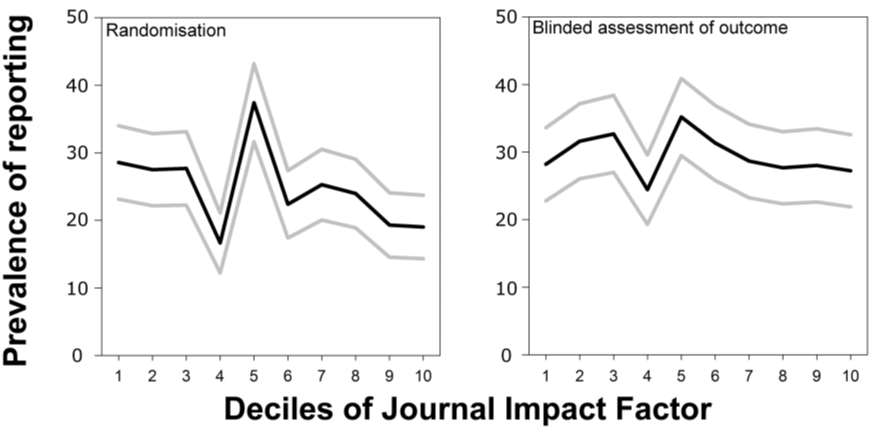

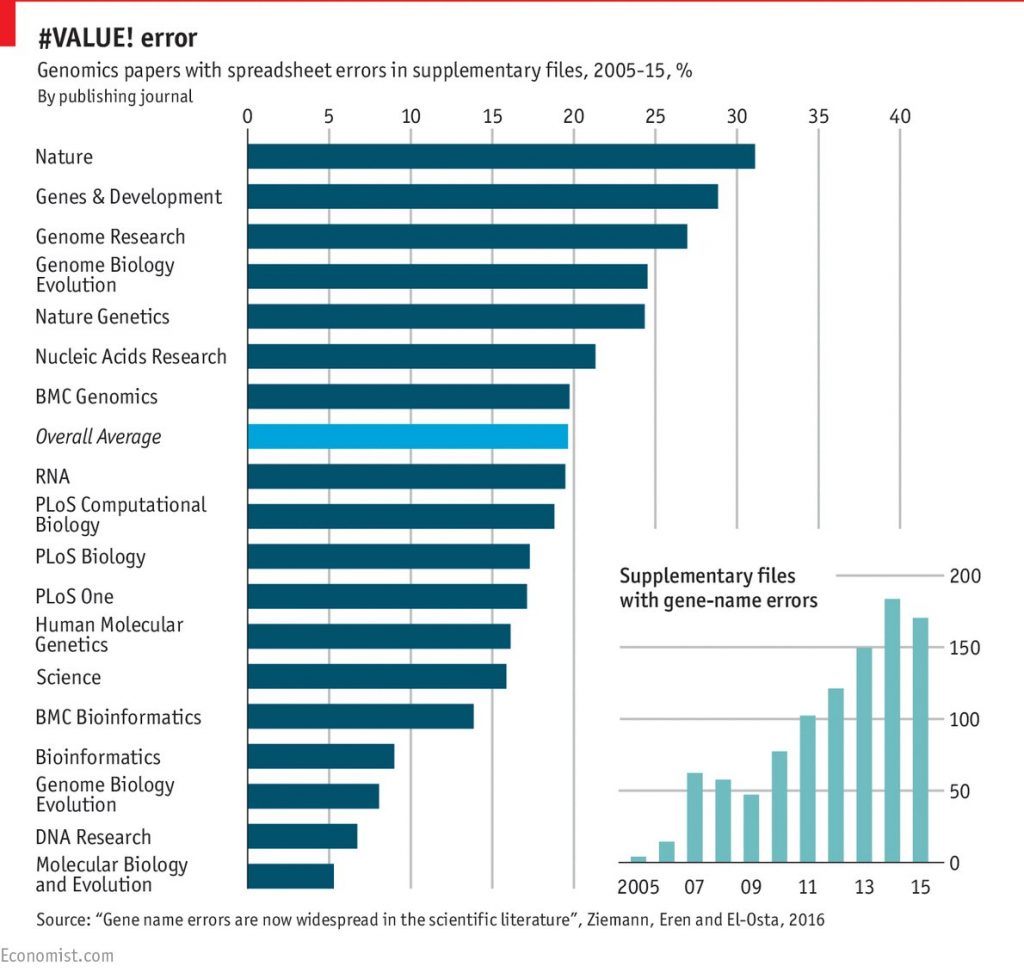

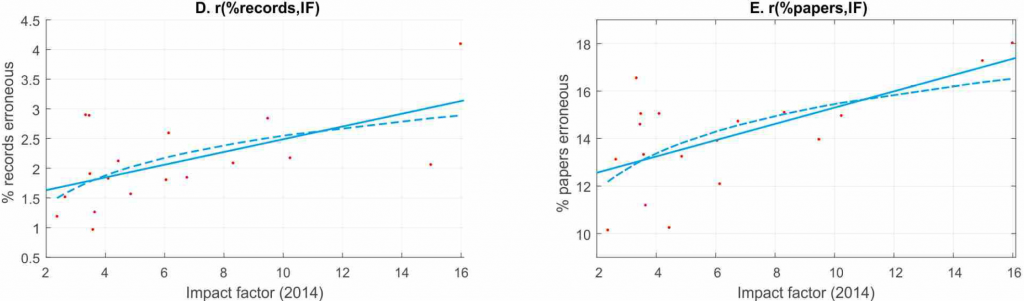

One might argue that without library deals, the journals compete for authors, keeping prices down. This argument forgets that we are not free to choose where we publish: only publications in high-ranking journals will secure your job in science. These journals are the most selective of all journals. In the extreme cases, they only publish 8% of all submitted articles. This is an expensive practice as even the rejected articles generate some costs. It is hence not surprising that also among open access journals, APCs correlate with their standing in the rankings and hence their selectivity (Nature Communications being hence just a case in point). In fact, this relationship is the basis for pricing strategies at SpringerNature (the corporation that publishes the Nature brand): “Some of our journals are among the open access journals with the highest impact factor, providing us with the ability to charge higher APCs for these journals than for journals with average impact factors. […] We also aim at increasing APCs by increasing the value we offer to authors through improving the impact factor and reputation of our existing journals.” It is reasonable to assume that authors in the future scenario will do the same they are doing now: compete not for the most non-selective journals (i.e., the cheapest), but for the most selective ones (i.e., the most expensive). Why should that change, only because now everybody is free to read the articles? The new publishing model would even exacerbate this pernicious tendency, rather than mitigate it. After all, it is already (wrongly) perceived that the selective journals publish the best science (they publish the least reliable science). If APCs become predictors of selectivity because selectivity is expensive, nobody will want to publish in a journal without or with low APCs, as this will carry the stigma of not being able to get published in the expensive/selective journals.

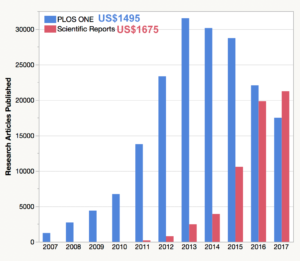

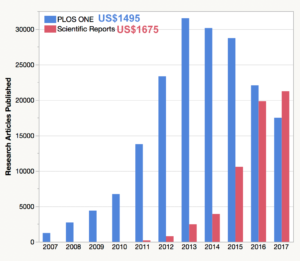

There are even data to suggest that this is already happening. PLoS One and Scientific Reports (another Nature brand journal) are near identical megajournals, which essentially only differ in two things: price and the ‘Nature’ brand. If competition would serve to drive down prices, authors would choose PLoS One and shun Scientific Reports. However, the opposite is the case, falsifying the hypothesis that a gold Open Access market would serve to keep prices in check:

Proponents of the “competition will drive down prices” mantra will have to explain why their proposed method fails to work in this example, but would work if all journals operated in the same way. One could go one step further: just as scholars now are measured by the amount of research funds (grants) they have been able to attract for their research in a competitive funding scheme, it seems only consequential to then also measure them by the amount of funds they were able to spend on their publications in a competitive publications scheme, if the most selective journals are the ones charging the highest APCs: the more money one has spent on publications, the more valuable their research must be. In other words, researchers will actively strive to only publish in the most expensive journals – or face losing their jobs.

Also here, we are already seeing the first evidence of such stratification in terms of who can afford to pay to publish in prestigious journals. A recent study showed that higher ranked (thus, richer and more prestigious) universities tend to pay more for open access articles in higher ranking journals, while authors from lower ranking institutions tend to publisher either in closed access journals or cheaper open venues. Thus, the new hierarchies are already forming, showing us how this brave new APC world will look like.

This, to me as a non-economist, seems to mirror the dynamics of any other market: the Tata is no competition for the Rolls Royce, not even the potential competition by Lamborghini is bringing down the prices of a Ferrari to that of a Tata, nor is Moët et Chandon bringing down the prices of Dom Perignon. On the contrary, in a world where only Rolls Royce and Dom Perignon count, publications in journals on the Tata or even the Moët et Chandon level will only be ignored. Moreover, if libraries keep paying the APCs, the ones who so desperately want the Rolls Royce don’t even have to pay the bill. Doesn’t this mean that any publisher who does not shoot for at least US$5k in their average APCs (better more) fails to fulfill their fiduciary duty in not one but two ways: not only will they lose out on potential profit, due to their low APCs, they will also lose market share and prestige. Thus, in this new scenario, if anything, the incentives for price hikes across the board are even higher than what they are today. Isn’t this scenario a perfect storm for runaway hyperinflation? Do unregulated markets without a luxury segment even exist?

Of course, if libraries refuse to pay above a certain APC level (i.e., price caps), precariously employed authors won’t have any other choice than to cough up the cash themselves – or face the prospect of flipping burgers. Coincidentally, price caps would entail that those institutions which introduce these caps, have to live with the slogan “we won’t pay for your Nature paper!”, so I wonder how many institutions will actually decide to introduce such caps and what this decision might mean for their attractiveness for new faculty.

One might then fall back on the argument that at least journal-equivalent Fiat will compete with Journal of Peugeot for APCs, but that forgets that a physicist cannot publish their work in a biology journal. Then one might argue that mega-journals publish all research, but given the constant consolidation processes in unregulated markets (which is alive and well also in the publishing market as was recently reported), there quickly won’t be many of these around any more. As a consequence, they are, again, free to increase prices. Indeed, NPG’s Scientific Reports has now overtaken PLoS ONE as the largest mega-journal, despite charging more than PLoS ONE, as shown in the figure above. No matter how I try to turn the arguments around, I only see incentives for price hikes that will render the new system just as unsustainable as the current one, only worse: failure to pay leads to a failure to make your discovery public and no #icanhazpdf or Sci-Hub can mitigate that. Again, as in all scenarios and aspects discussed above, also this kind of scenario can only be worse than what we have now.

In the end, it seems the trust in ‘market forces’ and ‘competition’ to solve these problems for us is about as baseless and misguided as the entire neoliberal ideology from which this pernicious faith springs.

At the very least, if there ever should be universal gold OA, the market needs to be heavily regulated with drastic, enforced, world-wide, universal price caps much below current article processing charges, or the situation will be worse than today: today, you have to cozy up with professional editors to get published in ‘luxury segment’ journals. In a universal OA world, you would also have to be rich. This may be better for the public in the short term, as they then would at least be able to access all the research. In the long term, however, if science suffers, so will eventually the public. In today’s world, one needs some tricks to read paywalled articles, such as Sci-Hub or #icanhazpdf or friends at rich institutions. In this brave new universal gold OA world, you need cold, hard cash to even be able to get read. Surely, unpublished discoveries must be considered worse than hard-to-read, but published discoveries?

Thus, from any perspective, gold OA with corporate publishers will be worse than even the dreaded status quo. [UPDATE I: After I wrote this post, the American Research Libraries posted an article pretty much along the same lines, emphasizing the reduced market power of the individual authors above and beyond many of the same concerns I have raised above. Clearly, a quick analysis by anyone will reveal the unintended consequences of merely ‘flipping’ existing journals to an APC-based OA format. UPDATE II: A few month after this post, a recent study by several research-intensive universities in the US also came to the same conclusions as the ARL and yours truly: “the total cost to publish in a fully article processing charge-funded journal market will exceed current library journal budgets”]

Obviously, the alternative to gold OA cannot be a subscription model. What we need is a modern scholarly infrastructure, around which there can be a thriving marketplace of services for these academic crown jewels, but the booty stays in-house. We already have many such service providers and we know that their costs are at most 10% of what the legacy publishers currently charge. How can we afford such a host of modern functionalities and get rid of the pernicious journal rank at the same time?

Institutions with sufficient subscription budgets and the motivation to reform will first have to coordinate with each other to safeguard the back issues. Surprisingly, there are still some quite substantial technical hurdles, but, for instance, a cleverly designed combination of automated, single-click inter-library loan, LOCKSS and Portico by the participating institutions, should be able to cover the overwhelming part of the back archives. For whatever else remains, there still is Sci-Hub et al.

Once the back-issues are made accessible even after subscriptions run out, a smart scheme of staged phasing out of big subscription deals will ensure access to most of these issues for at least 5 years if not more. In this time, some of the freed funds from the subscriptions can be used to pay for single article access for newly published articles. The majority of the funds would of course go towards implementing the functionalities which will benefit researchers to such an extent, that any small access issues seem small and negligible in comparison.

In conclusion, there is no way around massive subscription cuts, both out of financial considerations and to put an end to pernicious journal rank. If cleverly designed, most faculty won’t even notice the cuts, while they simultaneously will reap all the benefits. Hence, there is no reason why people without infrastructure expertise (i.e., faculty generally), should be involved in this reform process at all. Much like we weren’t asked if we wanted email and skype. At some point, we had to pay for phone calls and snail mail, while the university covered our email and skype use. At some point, we’ll have to pay subscriptions, while the university covers all our modern needs around scholarly narrative (text, audio and video), data and code.

It’s clearly not trivial, but the savings of a few billion dollars every year should grease even this process rather well, one would naively tend to think.

UPDATE III (14/12/2017): Corroborating the arguments above, a recent analysis from the UK, a country who has favored gold Open Access for the last five years, comes to the conclusion that “Far from moving to an open access future we seem to be trapped in a worse situation than we started“. I think it is now fair to say that gold open access is highly likely to make everything worse (rather than ‘may‘ as in the title of this post). UPDATE to the update (08/05/2018): A Wellcome Trust analysis also found average APCs to rise between 7% and 11%, i.e., double to triple inflation rate, year over year. Clearly, if more and more gold OA journals indeed would lead to more competition, it’s not driving down prices, on the contrary.

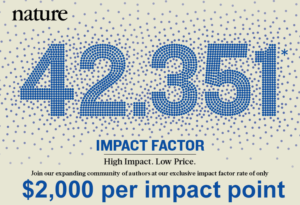

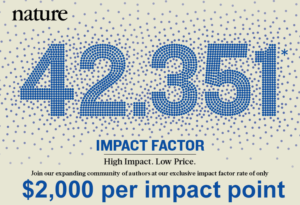

UPDATE IV (19/12/2017): I just went back to Nature‘s old statement in front of the UK parliament, added about 6% in annual price increases (a bit above APC increases and a bit below subscription increases, see above) and arrived at about £22,600-£67,800 that Nature would need to charge for an article in their flagship journal, if they went gold open access today. At current exchange rates, this would amount to about US$30,000-90,000. Rounded out to about US$1000-2000 per impact point:

If one looks at Nature’s actual subscription increases from 2004 to today, they are much lower and amount to an increase of about 25%. This would bring us to pretty much exactly US$50,000 per article, at the current exchange rate. So depending on how one calculates, 30-90k per article for a high impact journal seems what has to be expected.

If one looks at Nature’s actual subscription increases from 2004 to today, they are much lower and amount to an increase of about 25%. This would bring us to pretty much exactly US$50,000 per article, at the current exchange rate. So depending on how one calculates, 30-90k per article for a high impact journal seems what has to be expected.

UPDATE V (14/09/2018): At the persistent request from a reader, I’m extending the discussion on the content of this post to a more suitable forum.

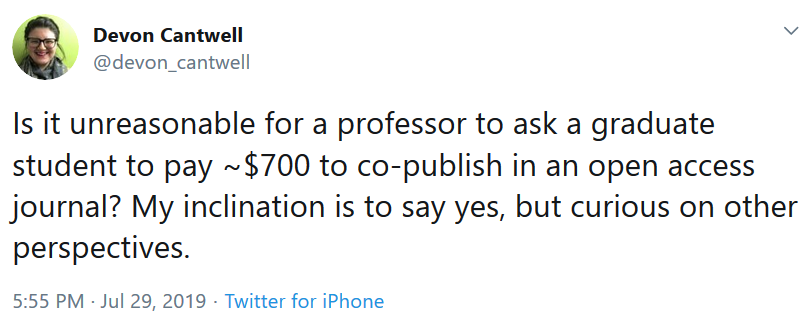

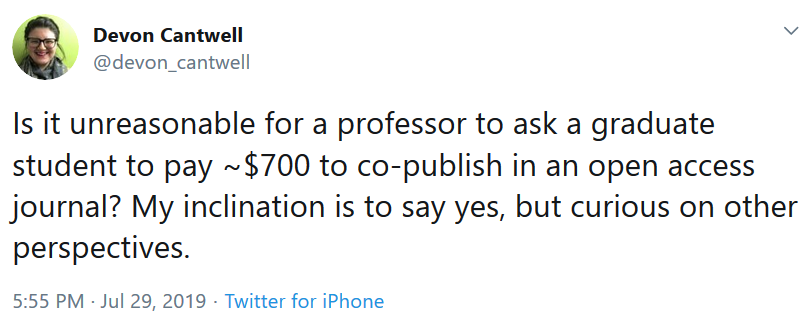

UPDATE VI (30/07/2019): Not surprisingly, students are being asked to co-pay the APCs:

Clearly, those who find tuition fees reasonable will argue that this is the best investment in their career that the PhD student can make. Those who argue that price sensitivity of authors will help bring down publisher prices will also find this very reasonable.

Clearly, those who find tuition fees reasonable will argue that this is the best investment in their career that the PhD student can make. Those who argue that price sensitivity of authors will help bring down publisher prices will also find this very reasonable.

Like this:

Like Loading...